![]()

Part I

Theoretical Considerations

There are many factors that contribute to the successful creation of a new family for children who cannot stay with their birth families. The contribution made by a child mental health service must be seen in the broader context of the wider community and in relation to post-placement support services. The range of resources that are or should be available have been addressed comprehensively by Argent (2003), but the availability of social work, with appropriate financial, legal, housing, and educational advice, is crucial.

Families who come forward to care for looked-after children do not necessarily see themselves as requiring psychological help and, by contrast, are likely to be assessed as well-functioning and capable of dealing with complex and challenging issues. However, it is now also absolutely clear that for many families help that addresses the emotional aspects of caring for looked-after and adopted young people is needed to ensure a successful outcome, especially for the most troubled. There is a need to develop knowledge and understanding of the impact of these children’s earlier experiences on their development and behaviour and to acquire new and specific parenting skills, which may not have been relevant previously. Having been through the lengthy process that leads to achieving a child’s placement, however, many families wish to be left to get on with the task of caring for the new family member without outside involvement. It is important that they will, as part of the process, have been helped to see that they are taking on a responsibility for which ordinary life does not necessarily prepare them well enough, and that accepting psychological support for themselves and their families is not going to be a sign of failure in any way. This means that it is an advantage if help can be provided in a non-stigma-tizing manner and setting, as, for example, is work done by the voluntary organizations.

It is not just the parents who need help in adjusting to the demands made on them to care for the child, but also the child who needs help to adjust to living permanently in a family. The demands of ordinary family life for intimacy and reciprocity are very great for someone whose experience of close relationships has been one of rejection, abuse, and neglect. Families can more readily see that the child may need help with these issues but have a variety of responses, ranging from “we can help them ourselves” to “you deal with the child and leave us out of it”. Our experience is that, almost inevitably, a mixture of interventions is required, which involve the family, the parents, and the young person, together and separately. It is crucial when asking them to engage on this work to convey the understanding that the family did not create the problems being presented, so that they do not feel pathologized and that their difference from other families, of being an alternative, not a birth family for this child, is recognized.

Children and their families may be referred at various points in the process from the point at which a decision has been made that they should be permanently placed—for example, transitional work—to work with families who are having problems after a placement has been made or after the adoption, sometimes several years later. All referrals are likely to have in common a high level of concern about the functioning of the child in more than one setting, usually both at home and at school, together with a recognition of the impact of the child’s history on the ability to make new relationships as well as the ongoing effect of the birth family, whether in reality or in the mind. There is often a complex family–professional system, involving shared responsibilities, between social workers and family, with education always having an important role to play.

The issues being presented clinically are conceptualized using a number of theoretical frameworks. Each of these describes the difficulties from a particular perspective and also provides a guide to potential interventions. The team works together in an integrated way. The contribution of each discipline is respected, and the range of therapeutic modalities is seen as complementary. An attempt is made to see the problems of the children and their families from several perspectives and to create a “multiversa” (Maturana, 1988) rather than have one explanatory model to fit all. In the Tavistock team use is made of systemic, psychoanalytic, attachment, psychological, and psychiatric theoretical models to inform both assessment and intervention. We think it may be helpful to the reader if we set out these frameworks at the beginning of this book as we see them applying to work in the field of fostering and adoption. Each chapter within part I shows how the concepts described are particularly relevant to work with the children and their foster, adopted, and kinship families.

Caroline Lindsey

![]()

Chapter 1

A systemic conceptual framework

Caroline Lindsey and Sara Barratt

The systemic model has long been associated with seeing families in family therapy. Systemic practitioners have extended their practice more broadly into the wider domain of human systems, not exclusively focused on families, but applying the systemic approach also to work with individuals and couples as well as to training, consultation and liaison with professionals and agencies. A system is a name given to a set of relationships created between people characterized by a pattern of connectedness over time. Individuals in a system are seen to affect and be affected by each other in what is described as a circular way. This is in contrast to the idea that many hold, that one person affects the other unidirectionally—that is, in a linear fashion. Systemic therapists, however, also recognize that some people in a relationship may have, or be seen to have, more power to influence what happens than others—for example, parents often having more physical strength to impose their wishes on children. Systemic therapists intend to intervene to enable individuals to alter the balance of relationship between them, on the basis that the way the relationships are organized maintains or even creates the problems which are the source of their concern. Problems are not conceptualized as being located within the individual. Working systemically means that it is possible to choose to work, not simply with a family who live together, but to invite all those who are contributing to or have a role in constructing the problem that needs to be addressed: “the problem-determined system” (Anderson, Goolishian, & Windermere, 1986). The systemic approach is a crucial aspect of working with families who foster and adopt and with the professionals and agencies involved in their care. It offers a framework for understanding and intervening in the inter-relationships between the complex systems created for caring for children outside their birth families. Practitioners are seen as part of a new “co-created” system, which is formed between themselves and the families and other professional participants in the course of the conversations that they have together. The therapist actively participates in the creation of the story which emerges in the session, through questions which are asked or which remain unasked and by the interventions which are made. This contrasts with an idea that is sometimes held, that it is possible for therapists to act on the family from an outside, external position without being affected themselves.

Context

Context is a key concept. According to Bateson (1979), “without context, words and actions have no meaning at all”. Context is defined, among other characteristics, by markers such as place, time, relationship, and language. The many varied contexts in which we live and work influence our behaviour, beliefs, and understanding of the meaning of our experiences and relationships, so that we may see ourselves and be seen by others as being different, depending on the context. For children who are cared for in alternative forms of families, the idea of family and family relationships is fraught with difficulty. There is no easy understanding of the meaning of everyday concepts, such as mother and father, daughter and son relationships for those young people who have experienced abuse and neglect at the hands of those people who are supposed to care for them and for whom, as they have moved from one place to another, home does not mean a place where you feel secure—“at home”. In order to understand children’s behaviour in these circumstances it is crucial to make no assumptions about the meaning of family life for them. Attachment theory (see chapter 3) describes a specific contextual relationship marker between caregivers and child. Bowlby (1969) described a system that ideally develops to create security in the face of fear and the unknown, in which the child experiences the parent as a figure of attachment who responds with appropriately sensitive caregiving. The pattern of attachment developed by the child is one of several aspects of the parent–child relationship. In cases where the child has to move to a new home, it plays a crucial part in the way the pattern of future relationships evolves. Systemic therapists use the understanding that flows from attachment theory in working with relationships.

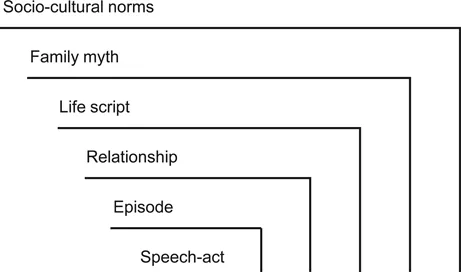

“The Coordinated Management of Meaning”

The “Coordinated Management of Meaning” (Pearce & Cronen, 1980) is a framework that conceptualizes the multi-layered levels of context in which we live our lives. The model is helpful in conceptualizing the complexity of alternative forms of family life. The levels include the socio-cultural norms of society, family or team context, life script whether personal or professional, relationship context, episode, and speech-act (Figure 1.1). Each level provides a context for every other level, reflexively. At times the meanings at one level are in contradiction with those at another level, which may account for the difficulties of individuals either in their personal or in their professional lives. It is with these contradictions of meaning in context that systemic therapists must concern themselves. Professionals working in this field may also experience contradictions between their personal beliefs and professional duties and agency role, which may affect their relationship with the family, other workers, and to the task.

FIGURE 1.1. The Coordinated Management of Meaning (Pearce & Cronen, 1980).

The socio-cultural level of context powerfully defines the lives of families who foster or adopt, of the children as well as their birth families, since it includes the legislative framework by which the families are created, societal beliefs about parental entitlement, rights, duties and responsibilities, and the beliefs about parenthood and family life held by different cultural, ethnic, and religious communities. Professionals are also organized in their thinking and practice by their personal and professionally held beliefs and experiences. It is important for them to consider how ideas of difference in race and ethnicity, religion, class and culture, gender, age, and ability affect the meaning they give to their own lives and the families and colleagues with whom they work.

Within the level of what Pearce and Cronen term the family myth and to which Byng-Hall (1995) refers as family script are embedded the many different forms that make up the constellation of families in this field, referred to elsewhere as “a Family of Families” (Lindsey, 1993). Families hold a range of beliefs and patterns of relating, developed over generations, based on how they are brought into being and with whom. If we confine ourselves to considering foster, adoptive, kinship care, and birth families in relation to their sense of connectedness over time, it will immediately be apparent how different the experience of family life might be in each context for the child or young person. In the case of the first two, there is no mutually held family history over previous generations, joining child and parents, which in birth families and in kinship care is often the cement that holds otherwise precarious relationships together. The family’s unique script is created by the intergenerational experience of family life and their specific cultural heritage, affecting the way they see the nature of parenting. The script plays a crucial role in the adaptation of those families who, for example, adopt as a consequence of infertility or the meaning of caring for a relative through kinship care.

The level of life script gives meaning to the family member as an individual, telling the story that runs: “I am the kind of person who….” The life story of children in the care system usually contains a script of loss and rejection, of hurt, neglect, and abuse which often defines the way they perceive themselves and how they expect to be treated in the future. These experiences may lead them to see themselves as unlovable and blameworthy and to develop ways of behaving which address their need to be self-reliant and controlling of their environment. It may show in parentified behaviour, reflecting a story that they tell themselves, based on earlier experiences, that they need to take care of the parent, for whom they feel responsible. This then contributes to the way in which new relationships with foster and adoptive parents may form, based on the script, rather than, as everyone hopes, on the new opportunity for attachment. When a positive relationship between the new family members does develop, the young person may sometimes experience a conflict of loyalty and worry about the birth parent, based on earlier family ties and relationships. This may then give rise to often disturbing patterns of relating to each other—for example, tantrums, or withdrawal on attempts to offer affection or discipline—within the new relationship, which should be understood contextually. These disturbances can be described as episodes. Within this schema, the family relationships may define the meaning given to these patterns, and the family relationship, in turn, is defined by the episodes. Parents describe how they find themselves behaving in ways that they do not recognize, evoked by the child’s repeated behaviour patterns, which defines their relationship in a potentially negative way. Often there are characteristic pieces of behaviour or ways of talking—“speech-acts”—which are meaningful to all the family members and may, in turn, define patterns of relating within the relationship. Ordinary everyday requests or reprimands may trigger verbal and behavioural responses based on the prior terrifying meaning of such communications for the young person. This may, then, lead to an escalation that resonates at all the other levels of meaning, of relationship, life script, and family life. It is often related to issues such as a refusal to eat or hoarding of food, for example, with parallel and significant meanings for both child and parent.

There are often potential contradictions in their role and task for professionals in the team. All child mental health work is contextualized by the socio-cultural framework, which includes the law of the country. However, in this field, professionals have frequently to move from a position where they have to take action—for example, in relation to child protection concerns—or to take a position by writing a court report—termed being in the domain of production (Lang, Little, & Cronen, 1990)—to a position where they are hoping to work therapeutically with a family, called being in the domain of explanation. Clarifying in which domain the clinician is operating is essential to enable practitioner and family to give meaning to their conversations.

Family life cycle

The idea of a family life cycle has been used in family therapy as a tool in conceptualizing the stages of family development. It can usefully be adopted for thinking about the stages that newly forming foster and adoptive families go through, including their decision to seek help. For many foster and adoptive families who are selected on the basis of their ability to function autonomously, the idea of asking for help may be in contradiction to their family script and is reached often only when they have exhausted their own resources. It is self-evident that the value of the life-cycle framework is to act as a guide rather than to create rigid expectations. An example of such a schema is presented in Table 1.1. The life-cycle concept enables the clinician to normalize the experiences that families are having, which seem different to what they had been expecting, based on what had happened previously in their birth family. For example, there may be issues of the timing of autonomous and independent behaviour and an expectation of when past wounds should have been healed. A commonly expressed concern by adoptive parents is why their child has not yet “got over” their trauma and “settled down”. Being able to refer to an accepted “norm” of a much longer timescale required for children placed from care to adapt to their new environment is reassuring to parents. The explanation that the child’s slow development may be to be expected, considering their past deficits of care, and is not a fault inherent either in the child or in their current parenting, reduces unrealistic expectations, guilt, and anxiety. The particular issues for fostered and adopted children can be embedded in the stages of the life cycle of the family. Key stages such as going to school, enteri...