- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fathers, Families and the Outside World

About this book

This is the second monograph to be published under the auspices of Winnicott Studies, the Squiggle Foundation's renowned series of publications on contemporary applications of Winnicott's thought. Like its predecessor, which concentrated on the True and False Self, this volume focuses on a single topic: Winnicott's treatment of fathers. The volume includes a reprint of Winnicott's 1965 paper, "A child psychiatry case illustrating delayed reaction to loss", which is followed by John Forrester's "On holding as a metaphor", which expands and comments on many of the issues which Winnicott raises. John Fielding then provides an insight into Shakespeare's treatment of father-figures; Graham Lee outlines a new approach to the Oedipus complex in the light of Winnicott's insights; and Val Richards concludes with some clinical and theoretical thoughts. Taken together, these papers provide an intriguing composite picture of Winnicottian thought today, on a topic which is of increasing social and cultural interest.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fathers, Families and the Outside World by Gillian Wilce, Val Richards in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

A child psychiatry case illustrating delayed reaction to loss

Written for a collection of essays in memory of Marie Bonaparte, 19651

On his eleventh birthday Patrick suffered the loss of his father by drowning. The way in which he and his mother needed and used professional help illustrates the function of the psychoanalyst in child psychiatry.

In the course of one year Patrick was given ten interviews and his mother four, and during the four years since the tragedy occurred I have kept in touch, by telephone conversations with the mother, with the boy’s clinical state as well as with the mother’s management of her son and of herself. The mother started with very little understanding of psychology and with considerable hostility to psychiatrists, and she gradually developed the qualities and insight that were needed. The part she was to play was, in effect, the mental nursing of Patrick during his breakdown. She was very much encouraged by being able to undertake this heavy task and by succeeding in it.

Family

The father had a practice in one of the professions. He had achieved considerable success and had very good prospects. Together they had a large circle of friends.

There were two children of the marriage, a boy at university and Patrick, who was a boarder at a well-known preparatory school. The family had a town house in London and a holiday cottage on an island off the coast. It was in the sea near the holiday cottage that the father was drowned when sailing with Patrick on the day after his eleventh birthday.

The evolution of the psychiatrist’s contact with the case

The evolution of the case is given in detail and as accurately as possible because this case illustrates certain features of child psychiatry casework which I consider to be vitally important.

Whenever possible I get at the history of a case by means of psychotherapeutic interviews with the child. The history gathered in this way contains the vital elements, and it is of no matter if in certain aspects the history taken in this way proves to be incorrect. The history taken in this way evolves itself, according to the child’s capacity to tolerate the facts. There is a minimum of questioning for the sake of tidiness or for the sake of filling in gaps. Incidentally, the diagnosis reveals itself at the same time. By this method one is able to assess the degree of integration of the child’s personality, the child’s capacity for holding conflicts and strain, the child’s defences both in their strength and in their kind, and one can make an assessment of the family and general environmental reliability or unreliability; and, in certain cases, one may discover or pinpoint continuous or continuing environmental insults.

The principles enunciated here are the same as those that characterize a psychoanalytic treatment. The difference between psychoanalysis and child psychiatry is chiefly that in the former one tries to get the chance to do as much as possible (and the psychoanalyst likes to håve five or more sessions a week), whereas in the latter one asks: how little need one do? What is lost by doing as little as possible is balanced by an immense gain, since in child psychiatry one has access to a vast number of cases for which (as in the present case) psychoanalysis is not a practical proposition. To my surprise, I find that the child psychiatry case has much to teach the psychoanalyst, though the debt is chiefly in the other direction.

First contact

A woman (who turned out to be Patrick’s mother) telephoned out of the blue to say she had reluctantly decided to take the risk of consulting someone about her son, who was at a prep school, and she had been told by a friend that I was probably not as dangerous as most of my kind. I certainly could not have foretold at this initial stage that she would prove capable of seeing her son through a serious illness.

I was told that the father had been drowned in a sailing accident, that Patrick had been to some extent responsible for the tragedy, and that she, the mother, and the older son, were still very disturbed and that the effect on Patrick had been complex. The clinical evidence of disturbance in Patrick had been delayed and it now seemed desirable that someone should investigate. Patrick had always been devoted to his mother, and since the accident had become (what she called) emotional.

In this brief account of a long telephone conversation I have not attempted to reproduce the mother’s rush of words or her scepticism in regard to psychiatric services.

First interview with Patrick (two months after this telephone conversation)

Patrick was brought by his mother. I found him to be of slight build, with a large head. He was obviously intelligent and alert and likeable. I gave him the whole time of the interview (two hours). There was no point in the interview at which the relationship between him and me was difficult. Only during the most tense part of the consultation was it impossible for me to take notes. The following account was written after the interview.

Patrick said he was not doing very well at school, but he “liked intellectual effort”. We were seated at a low round table with paper and pencils provided, and we started with the Squiggle Game. (In this I make a squiggle for him to turn into something, and then he makes one for me to do something with.)

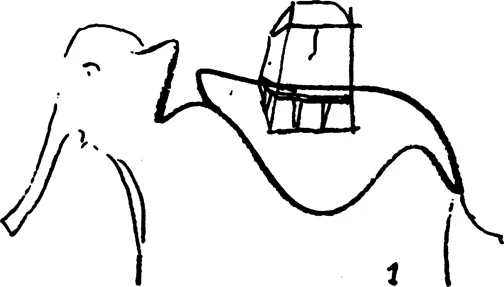

- He made mine into an elephant.

- He made his own into “a Henry Moore abstract.” Here he showed that he was in contact with modem art and later it became clear that this is something which belongs to his relationship to his mother. She takes an active part in keeping him well informed in the art world, which has been important to him since the age of five years. It also shows his sense of humour, which is important prognostically. It shows his toleration of madness and of mutilation and of the macabre. It might be said that it also shows that he has talent as an artist, but this comes out more clearly in a later drawing. His choosing to turn his squiggle into an abstract was related to the danger, very real in his case, that because of his very good intellectual capacity he would escape from emotional tensions into compulsive intellectualization; and because of paranoid fears, which later became evident, there could be a basis here for an organized system of thought.

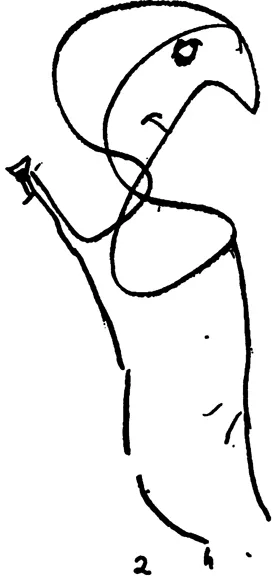

- I turned his squiggle into two figures which he called “mother holding a baby.” I did not know at the time that here was already an indication of his main therapeutic need.

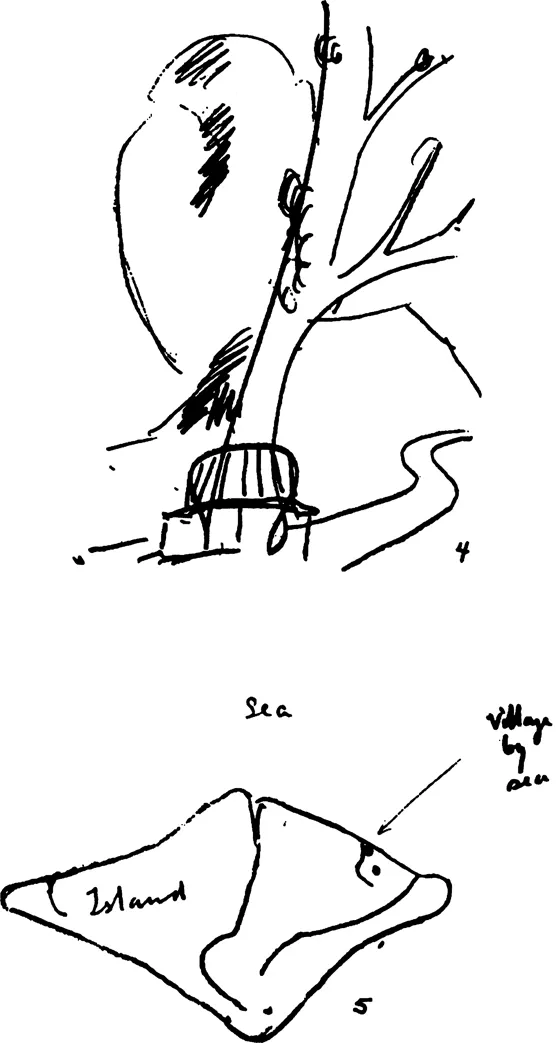

- He turned mine into an artistic production. It was done quickly and he knew exactly what he was doing. He said it was a tree at F. I did not know at that time that F. was the site of the tragedy, but in this drawing there was already incorporated his drive to cope with the problem surrounding his father’s death.

- This is his drawing, done at my request, of the holiday island, with F. shown.

- He turned his own into “a mother scolding a child,” and here one might see something of his wish to be punished by the mother.

- He turned mine into Droopy.

- I made his into some kind of a comical girl figure.

- This was important. He made my squiggle into a sculpture of a rattlesnake. “It might have been by a modern artist”, he said. In this case he took hold of a squiggle with all its madness and incontinence and turned it into a work of art, in this way gaining control of impulse that threatens to get out of control.

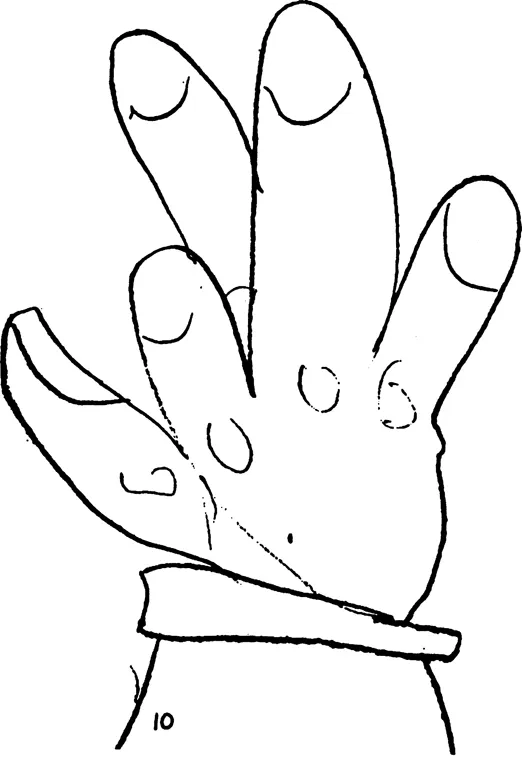

- In the next I turned his into some kind of a weird hand, and he said it might be by Picasso. This led to a discussion of Picasso in which he displayed his knowledge of Picasso in a way that sounded a little precocious. We agreed that the recent Picasso exhibition at the Tate Gallery was very interesting. He had been twice to it. He said he liked Picasso best in the “pink” and “blue” period and seemed to know what this meant, but I was aware that he was talking language which belonged to his discussion of these matters with his mother.

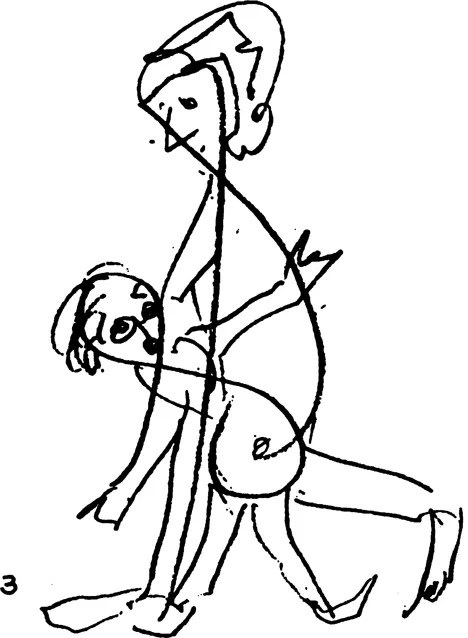

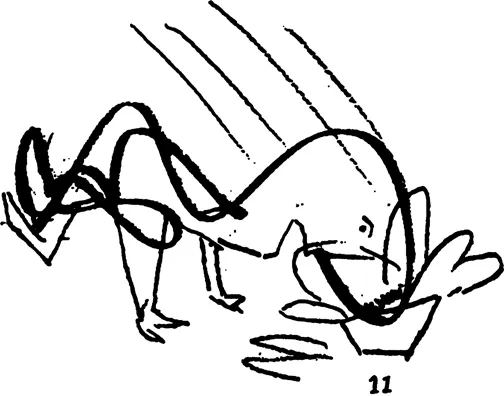

- This was rather a surprising picture. He made my squiggle into a person who slipped into some dog’s food. There is a lot of life in the picture, but I was not able to find out why this idea had turned up. I would think he was mocking me or perhaps all men.

He then started talking, and drawing became less important. What we talked about included the following:

In the first term at school he had had a dream. He had been ill with some kind of epidemic two nights before half-term, which he said is “an exciting time for a new bug.” In the dream the Matron told him to get up and go to the hall where the tramps are fed. The Matron shouted: “Is everyone here?” There were fifteen but one was missing; nobody knew that one was missing. It was weird in some way because there was no extra person. And then there was a church with no altar, and a shadow where the altar had been.

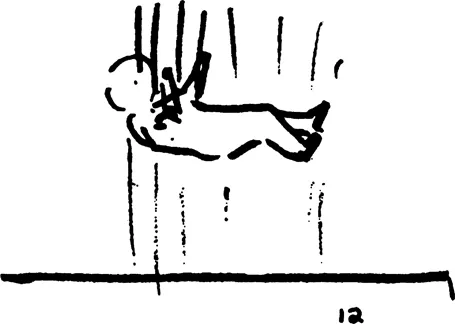

The rest had to do with a baby jumping up and down, of which he drew a picture (no. 12). The baby was screaming, going up and down on the mattress. He said that the baby was about 18 months old. I asked him whether he had known babies and he said: “About three.” It seemed, however, that he was referring in the dream to his own infancy. This dream remained obscure, but its meaning became elucidated in the fourth interview, four weeks later. It was thought that there was a reference to the dead father in the one person missing.

At this stage I did not know that he had not been told at once about his father’s death.

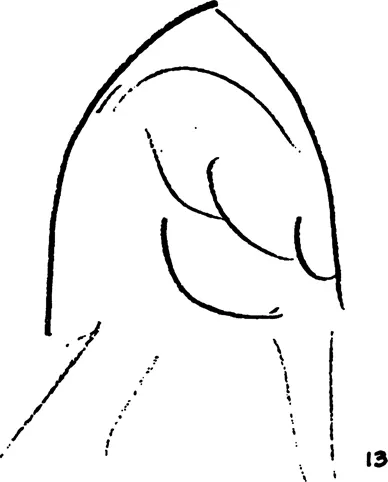

- 13. Here is his drawing of the church with a shadow instead of an altar. I asked: “What would be a nice dream?” He said quickly: “Bliss, being cared for. I know I want this.”

When I put the question he said he knew what depression was like, especially since father’s death. He had a love of his father, but he did not see him very much. “My father was very kind. But the fact is that mother and father were constantly under tension.” He went on to talk about what he had observed: “I was the link that joined them; I tried to help. To father it was outrageous to perarrange

anything. This was one of his faults. Mother would therefore complain. They were really very suited to each other, but over little things they would begin to get across each other, and the tension would built up over and over again, and the only solution to this was for me to bring them together. Father was very much

overworked. He may not have been very happy. It was a great strain to him to come home tired and then for his wife to fail him.” In all this he showed an unusual degree of insight.2

The rest of this long and astonishing interview consisted in our going over in great detail the episode in which his father died. He said that his father “may have committed suicide”3 or perhaps it was his own (Patrick’s) fault; it was impossible to know. “After a long time in the water one began to fight for oneself.” Patrick had a life belt and the father had none. They were nearly both drowned, but sometime after the father had sunk, just near dark, Patrick was rescued by chance. For some time he did not realize that his father was dead, and at first he was told that he was in the hospital. Then Patrick said that if his father had lived, he thinks his mother would have committed suicide. “The tension between the two was so great that it was not possible to think of them going on without one of them dying.” There was therefore a feeling of relief, and he indicated that he felt very guilty about this. (It will be understood that this is not to be taken as an objective and final picture of the parental relationship. It was true, however, for Patrick.)

At the end he dealt with the very great fears he had had from early childhood. He described his great fear associated with hallucinations both visual and auditory, and he insisted that his illness, if he was ill, antedated the tragedy.

- 14. This is a drawing of Patrick’s home with the various places marked in which persecutory male figures appear. The principal danger area was in the lavatory, and there was only one spot for him to use when urinating if he would avoid persecutory hallucinations.

There was a quality about this phobic system that seemed to belong more naturally to an emotional age of 4 rather than to 11 years, with phobias closely linked with hallucinations. The whole ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- CONTRIBUTORS

- Introduction: Papa versus Pooh

- CHAPTER ONE A child psychiatry case illustrating delayed reaction to loss

- CHAPTER TWO On holding as metaphor: Winnicott and the figure of St Christopher

- CHAPTER THREE “So rare a wonder’d father”: Winnicott’s negotiation of the paternal

- CHAPTER FOUR Alone among three: the father and the Oedipus complex

- CHAPTER FIVE “If father could be home…”

- REFERENCES

- INDEX