![]()

PART I

High Stakes

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The High-Stakes World of M&A

When companies merge or acquire, stakeholders rightly expect the whole to become greater than the sum of its parts. Unfortunately, this happens less than half the time. Not only does one plus one not equal three, but too often mergers and acquisitions (M&A) result in losses. A once exceptional organization can quickly take a turn toward mediocrity, or worse.

Study after study puts the failure rate of M&A between 70% and 90%. Many researchers have tried to explain these abysmal results, usually by analyzing the characteristics of deals that worked and those that didn’t. That’s a start, but it only informs decision makers about the features of the deals that caused or prevented failures. Statistics don’t truly get to the core of the cause–effect relationships among planning, evaluating, and integrating—the essential traits for successful M&A.

Deciding whether to do the deal presents the first round of tough calls, decisions about integration, the second. In the heat of finalizing the deal, leaders often leave integration until the last minute or give it short shrift. Leaders need clarity about what they should consider when they attempt to align two disparate organizational environments, histories, and cultures. When leaders make the decision to merge or acquire, they know the stakes are high, and they also know they can set the stage for success. Too often, however, these same leaders inadvertently invite dilemmas and disasters to come from the wings to take a bow in the spotlight.

Why does this happen? Because the leaders who made the initial decision to merge or acquire stop making the necessary tough calls to make the deal work. Realizing the dire consequences that can result, why would sane leaders choose to place themselves and their companies in the line of fire?

Why Do a Deal?

When a company considers an M&A deal, leaders need well-honed judgment, courage, vast experience, and unimpeachable integrity to make the tough calls associated with any growth initiative. Unfortunately, judging from the number of failed deals, most decision makers lack one or more of these four constructs. They also need, but frequently fail to obtain, a clear answer to the question, “Why do we want to do this deal?”

The answer to this question starts with the CEO and board of directors agreeing about why they want the deal, but then things get more complicated. The senior team, who must make the deal work, need to know why, and they need to be enthusiastic about the answer. Then, leaders need to test their conclusions with key groups and stakeholders. Otherwise, everyone involved will lose the energy needed to make the deal work. In these situations, companies end up with a lot of props but no performance.

For instance, if you had evaluated Blockbuster in 2002, while Netflix was in its infancy and the web still nascent technology, you would have given the company high marks as an acquisition target. You also probably would have advocated for integration of the two. But if you had asked how well prepared Blockbuster was to deal with emerging distribution systems, you would have felt less confident about the company’s ability to sustain even its own value. With some vision, you might have predicted that Blockbuster would be six years from irrelevancy and nine years from bankruptcy. The same test could apply to companies in the music and publishing industries over the past five to seven years.

When asking the reasons to do a deal, “We want to get bigger”—the response that often fuels the passion for a deal in the first place—is not the right answer. These reasons are better:

• Our reputation in the industry will skyrocket.

• We will attract top talent.

• We will improve our position with investors. Customers will benefit.

• We will enjoy better financial results.

• A combined organization will better position us to compete.

• Operational synergies become possible.

Another truth often fuels enthusiasm for deals. Many will deny and even decry this reason: “The other kids are doing it.”

When an industry consolidates, leaders wonder whether they are missing out by not acquiring or merging. Financing available? Why, yes, thank you, we’ll do a deal. These emotional and often unconscious motivations tug at decision makers, often relentlessly. Because professional people don’t like to say they want to borrow billions of dollars based on “gut feelings,” they conduct studies, analyze data, and hire consulting firms to validate their theses. The findings from this kind of research can build confidence in the future success of the deal, but ultimately, clear benefits like these should surface:

• Increased speed to market

• Increased revenue and margin

• More profit

• Synergy

• Integrated teams and coordinated efforts

• A bigger, stronger company uniquely positioned for growth

• A new high-performing combined culture

• A+ talent, the envy of others

• The avoidance of costly mistakes that could tarnish the brand

• Elimination of guesswork in choosing leaders for the newly created enterprise

• Rapid rewards of the merged organization

Obviously, no one says to McKinsey, “Validate my thesis.” But the desire to amass data to authenticate gut feelings often serves as a powerful motivator—even more so because people don’t admit why they want the data. The urge to respond to what Robert Cialdini calls “social proof”1 is profound and reliable among human beings. As Cialdini explained, the principle of social proof asserts that people think it appropriate for them to believe, feel, and act in ways that others also believe, feel, and act. No matter how smart they are, leaders are still human. We can deny what happens, laugh at it, or ignore it, but these reactions create the path to perdition—not to good deals.

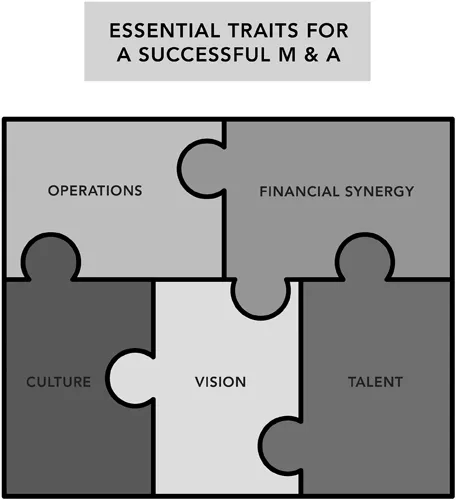

Five Essential Traits of a Successful Deal

Even if the decision to go forward with the deal is well formulated, more dilemmas surface during the integration stage. During both formulation and integration, leaders should consider the essential traits of a successful deal and apply these principles to other difficult decisions (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Essential traits.

A simple but clear vision helps you see where you’re going—a critical first step in formulating strategy. It defines what you want in the future; it inspires, motivates, and challenges. In conjunction with your corporate values, vision also helps you take a stand on all sorts of issues, including ethical ones.

Before discussing the company’s vision, however, leaders do well to revisit the mission. The mission clarifies why the organization exists; the vision identifies where the company intends to go; and the strategy specifies what everyone has to do to head into that ideal future. Vision comes from the mission, and strategy (which is shorter term and more specific) comes from both vision and mission—or at least it should.

Thinking about an organization’s future and imagining potential growth does not involve a tough call—at least not initially. Organic growth can happen slowly and deliberately, an approach that tends not to demand too much change too fast. It has an advantage in that people don’t usually fear organic growth. Nor do they need advanced critical thinking skills to formulate tactics for it. Even a little experience will serve to help replicate what you’ve done in the past. If the growth honors the mission of the organization, integrity issues typically don’t appear.

Decisions related to this kind of strategy formulation don’t usually involve tough calls—neither initially nor eventually. That may seem like a relief, but great leaders consider this safe zone more imaginary than real. A current rate of unacceptable growth is one reason leaders look to merge or acquire. When they do, the decisions they need to make will change markedly, and the speed at which they need to make them will accelerate. Most leaders find embarking on such a strategy far more challenging after many years of reliable, though slow, growth. When considering an M&A transaction, decision makers will face a particularly tough set of decisions about people. While a company may have many excellent people upon whom they can rely in the short run (even generating positive results in the near term), their reliability does not guarantee future success. Of course, decision makers will evaluate people in the usual ways—looking for evidence of a strong work ethic, high integrity, and effective interpersonal skills—but because deals tend to make things more complex, they will need to demand higher-caliber decision making among the talent in the new organization.

A key attribute that differentiates those who will succeed from those who will not involves the ability to discern. People with a keen ability to discern see patterns, anticipate consequences, and solve the complicated problems a deal invites. They have a finer ability to distinguish critical issues from unimportant ones, and they don’t easily lose sight of why things need to happen. They differentiate, detect, and determine the tough calls they should make and the essential criteria they must use. While important in all situations, the powers of discernment show their value most clearly in high-stakes situations such as M&A.

Brilliant talent, a breakthrough product, dazzling service, or cutting-edge technology can put you in the game, but only rock-solid execution of a well-developed strategy can keep you there, especially after a deal. You have to deliver—to translate your brilliant strategy and operational decisions into action. Your stakeholders will wait impatiently for these results, and they will usually fear the worst.

Therefore, you have to make things work—quickly. Even very smart leaders, in an effort to improve slipping performance, address the symptoms of reduced performance, not the root causes of it. Meanwhile, as the leaders look around to determine which changes they need to make, people in the organization get nervous. Nervous people are distracted people. Before you know it, they don’t have eyes on the ball. Rather, they abandon their roles as star players and assume that of umpire or critic—two roles you don’t need at any time. A focus on what’s going wrong instead of why you’re experiencing problems never works. Too often, people get distracted by emotions when they should search for logical explanations.

Successful deals start with a strong investment thesis—a clear objective about what the organization wants to accomplish. Clear strategy leads the process; great performance completes it. However, we often get confused. We over- and misuse strategy to describe anything important, and strategic planning becomes an oxymoron. Leaders formulate the strategy; they plan the execution—or at least the successful ones do. Execution involves discipline, requires senior leader involvement, and should be central to the organization’s culture. Done well, execution pushes you to decipher your broad-brush theoretical understanding of the strategy into intimate familiarity with how it will work, who will take charge of it, how long it will take, how much it will cost, and how it will affect the organization overall—and the customer, most importantly.

Operating plans often masquerade as strategic plans. (As an aside, we frequently insist that our clients talk about strategy and implementation plans. Strategic planning too often involves a list of goals or set of tactics from which it is impossible to derive solid decision criteria.)

In a newly merged organization, you don’t want your operating plan to concentrate on the past—to focus on the reflection in the rearview mirror. After all, at whose past would you be looking? And to what end? Furthermore, you will seriously undermine your ability to see the future. You’ll create an image more like the one you’d see in a fun-house mirror than an...