![]()

Part I

Why should we be concerned about children?

Children are the living messages to a time we will not see.

(Neil Postman, 1984)1

If we are to create peace in our world, we must begin with our children.

(Attributed to Mahatma Gandhi)

Reference

1 Postman, N. The disappearance of childhood. Vintage, 1984

![]()

1 Where have we come from?

When we sob aloud, the human creatures near us pass by, hearing not, or answer not a word.

(Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 1843)1

All children have the right to life. Governments should ensure that children survive and develop healthily.

(UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1959)2

The history of childhood is a nightmare from which we have only recently begun to awake. The further back in history one goes the lower the level of childcare and the more likely children are to be killed, abandoned, beaten, terrorised and sexually abused.

(Lloyd de Mause)3

The dogs are barking, but the caravan moves on.

(Arabic proverb, etymology unknown)

Historical perspective*

Unless we understand how our attitudes to children and childhood have developed, we won’t be able to improve the lives of our children now. How we have treated our children through the centuries and into today is an uncomfortable process.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that historians even bothered to study children as people in their own right and childhood as a specific entity. Philip Aries’ landmark book is still seen to be a milestone in the history of childhood.4

Nicholas Orme in his wonderful book5 on medieval children shows that during the Middle Ages a concern for the well-being of children was expressed for the first time. Children were seen to be different to adults and had their own culture.

Breughel’s painting Children’s Games in 15596 shows children playing more than 80 different games, many of which survive to this day The word ‘childhood’ emerged, describing how a child has to learn to read and write to become a good, God-fearing adult. The printed word spread schooling and education, Shakespeare describing ‘the whining schoolboy, with his satchel and shining morning face, creeping like a snail, unwillingly to school. How resonant today!7

John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau are key philosophers, with Locke arguing that a child’s mind, far from being a source of evil as in some aspects of the Christian tradition, was a tabula rasa or blank slate on to which it was the responsibility of adults to write.8 Rousseau’s view was different. He suggested that children have rights of their own (this idea remains controversial to this day); he was also concerned with the spirit of childhood – its joie de vivre – by writing about their sense of wonder and awe, the vigour and the enthusiasm of childhood.9 Rousseau also thought that children learn best through experience – a concept built on by Froebel and Montessori in their own distinctive approaches to teaching and education.10,11

The very different philosophies of Locke and Rousseau may have set the trajectories for the subsequent diverging approaches to children in society in Anglo-Saxon and European countries. For example, my good friend Clyde Herzman in Vancouver told me before he died that he had traced from the national archive of passenger lists of ships arriving from Europe how his family had immigrated to Canada. He noted that all children from France and Southern Europe were identified individually by name, e.g. Anne-Marie Boucher aged 2, whereas those from England were listed only as ‘child aged 2’, perhaps reflecting the view that children here were the chattels of parents and not individuals in their own right as in Europe.

The prevailing public view of childhood in eighteenth-century England was complex. Instead of being their custodians, adults often regarded their children as millstones around their necks. Many were abandoned. They were, quite literally, left out to die.

In London in medieval times, rich and poor lived cheek by jowl. After the Great Fire the rich migrated west and the poor to the east – a polarity that still exists today. The gulf between rich and poor fuelled an unprecedented crime wave. Newspapers – another new phenomenon – published sensational stories about highwaymen and murderers, designed to terrify their readers. The reality of crime, and the exaggerated fear of crime, made London a truly frightening place to live. Does this sound familiar today?

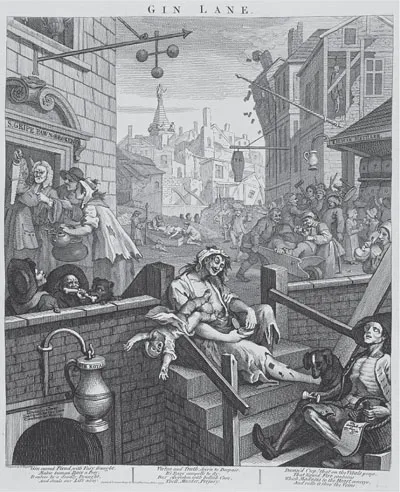

William Hogarth, the artist,12 was one of the first to portray the reality of children living in appalling social conditions. At that time, more than 50% of children died before they were 5 years old, illegitimacy was rife, and countless numbers of children were abandoned by parents ruined by the effects of gin – shockingly portrayed by Hogarth in his picture of Gin Lane in 1751 (Figure 1.1). There were no safety nets, no systems in place to support these children. How would Hogarth portray contemporary society, I wonder?

This was the situation Coram saw for unwanted babies left out to die, but it was not the picture throughout Europe, where foundlings had been cared for down the centuries.13 In Venice, for instance, an institution for foundlings had been established as early as the twelfth century – but not in England. Here there was a fear of encouraging promiscuity, as a contemporary quotation illustrates: ‘It is better for such creatures to die in a state of innocence than to grow up and imitate their mothers; for nothing better can be expected of them.’14 So, there was a world of difference then between Europe’s enlightened attitude to children and foundlings, and the deeply hostile approach in England.

Thomas Coram found himself fighting against this for the cause of foundlings. A man ‘of integrity and courage in an age of corruption and moral complacency’, Coram was as outraged as Hogarth at what he saw. He could not sit by and let these babies die.15

Coram’s inspiration was to harness the interests of 16 high-born ladies, 25 dukes, 31 earls, 26 other peers and 38 knights, and to couple their support to entrepreneurial fund-raising by engaging with the arts through Hogarth and Handel.

In October 1739, he was able to write: ‘After seventeen years and a half’s labour and fatigue I have obtained a charter for establishing a hospital for the reception, proper maintenance and employment of exposed and deserted young children.’15

The association between fund-raising, high society and the arts to support destitute, ill and disadvantaged children remains as powerful today as it was 300 years ago.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century basic education became more widely available particularly through Sunday schools fuelled by the indignation of churchmen intent on saving the souls of the poor.

The nineteenth century saw a significant divide for the middle and upper classes from others in education for boys and girls, with the creation of famous ‘public’ schools for boys, whose main function was to provide the servants of the emerging British Empire. In 1811 the Church of England created the National Society for Promoting Religious Education16 to give education to poor children across the country, the first attempt to provide systematic education. Its aim of establishing a church school in every parish led by 1850 to 12,000 schools across England and Wales, 20 years before the state took any responsibility for education. The National Society lives on today as the largest independent provider of education, supporting over 4,000 Anglican schools across England, working with the Children’s Society17 established in 1882 that continues to work for vulnerable children by research, reports and providing services.

In 1836 John Wesley the founder of Methodism and his successor the Reverend Jabez Bunting committed the movement to Christian education through creating a General Committee of Education. Some 600 Methodist schools were created alongside 150 others opened by other Free Church organisations. A strong input into teacher training persisted until the 1990s, a noteworthy contribution to the ethos of confronting poverty...