Child and Adolescent Drug and Substance Abuse

A Comprehensive Reference Guide

- 624 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Child and Adolescent Drug and Substance Abuse

A Comprehensive Reference Guide

About this book

By offering unique analysis and synthesis of theory, empirical research, and clinical guidance in an up-to-date and unbiased context, this book assists health and social care professionals in understanding the use of drugs and substances of abuse by children and adolescents.

A comprehensive reference for health and social care professionals, the book identifies and corrects related false narratives and, with the use of the authors' combined experience of over 70 years of clinical and academic experience in drug and substance abuse, provides current pharmacotherapeutic and psychotherapeutic approaches for the treatment of alcohol or other dependence or use disorders among children and adolescents. The book also provides a useful reference for identifying brand/trade and street names of the drugs and substances of abuse commonly used by children and adolescents. Also included is a comprehensive, cross-referenced subject index.

Clear, comprehensive, accessible, and fully referenced, this book will be an invaluable resource for professionals and students who aim to treat children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Drug and Substance Abuse is the 19th clinical pharmacology and therapeutic text that the Pagliaros have written over the past 40 years and is the sixth that deals exclusively with drug and substance abuse.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

Alcohol

- Achieve a desired dose-dependent disinhibition euphoria;

- Attain a sense of well-being;

- Be like “everyone else,” whose “parents let them do it;”

- Decrease social and sexual inhibitions;

- Fit in with peers;

- “Just have fun;”

- Relieve anxiety, tension, or stress—to “cope” with “life’s pains, disappointments, and impossible tasks.”1

- Long history of medical and personal use of alcohol in the U.S.;

- Identification of alcohol as a neurotoxin in humans;

- Discontinued medical use of alcohol as a “psychostimulant” during the last century;

- Cultural inculcation of alcohol into social gatherings, parties, and celebrations in the U.S.;

- Potential for significant alcohol-related physical, mental, and social harm, including severe and irreversible teratogenic effects—Fetal Alcohol Syndrome/Spectrum Disorder (FAS/FASD)—when used by adolescent girls and young women during pregnancy;

- Use of alcohol, in the U.S., as a “rite of passage” from adolescence to adulthood;

- Current use of alcohol by more than 80% of adolescents and young adults in the U.S.

Pharmacology

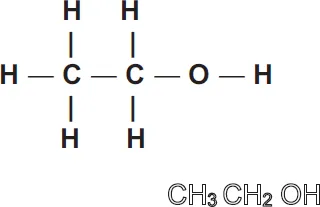

Chemistry

- “Type” of the alcoholic beverage ingested (e.g., beer versus whiskey);

- “Proof” (i.e., the equivalent to double the percentage concentration of the alcoholic beverage—for example, 40 proof indicates 20% alcoholic concentration);

- “Amount” of the alcoholic beverage ingested (e.g., one can of beer or a six-pack of beer) per unit of time (e.g., hour, day, or week).

Pharmacodynamics: Mechanism of Action and Blood Alcohol Concentrations

Mechanism of Alcohol Actions

- Alcohol readily crosses the blood-brain barrier disrupting the function of brain membrane lipids and glucose metabolism;

- Alcohol acts at two specific receptor sites in the brain—gamma aminobutyric acid (GABAA) receptor sites and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor sites (e.g., Brower, 2001; Gonzales & Jaworski, 1997; Pagliaro & Pagliaro, 2009; Peoples, Li, & Weight, 1996).

Blood Alcohol Concentrations

| BAC (gram % or grams per 100 ml) | Physical Effects | Mental Effects |

|---|---|---|

| 0.01 to 0.03 | Generally, normal appearance | Generally, normal behavior |

| 0.03 to 0.06 | Feel warm and relaxed with mild impairment of coordination and diminished ability to perform fine motor tasks | Mild euphoria (e.g., feelings of intense excitement and happiness) with decreased inhibitions and increased sociability and talkativeness Mild decreases in alertness and concentration |

| 0.06 to 0.08 | Increasing loss of coordination with a slight loss of both balance and speaking ability | Mild impairment of reasoning and memory with intensification of emotions Increased disinhibition euphoria with apparent “stimulant effect” on behavior and extroversion Lowered interest in sex |

| 0.08 to 0.10 | Mild imp... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Preface and Introduction

- Epigraph

- 1. Alcohol

- 2. Amphetamines and Cocaine

- 3. Caffeine and Nicotine

- 4. Cannabis and Other Psychodelics

- 5. Prescription Opiate Analgesics and Heroin

- 6. Prescription Sedative-Hypnotics

- Index