eBook - ePub

Media, Culture And The Environment

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Media, Culture And The Environment

About this book

This book is intended for final year undergraduates and postgraduates in cultural and media studies, as well as postgraduate and academic researchers. Courses on culture and the media within sociology, environmental studies, human geography and politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Media, Culture And The Environment by Alison Anderson,Alison Anderson University of Plymouth.,Anderson, Alison in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Pressure politics and the news media

Introduction

We live in a society in which mass communication is becoming an increasingly pervasive part of our lives. Everywhere one looks it is hard to escape from the images relayed by the media. With the development of new media technologies such as video, satellite, cable and the internet, the boundaries between nations are to some extent blurring. These new technologies have also profoundly changed political behaviour and the nature of political negotiation. In fact one theorist claims that the mass media: are “so deeply embedded in the [political] system that without them political activity in all its contemporary forms could hardly carry on at all” (Seymour-Ure 1974: 62). Election campaigns in advanced industrial societies, for example, have become highly managed media spectacles. Party image has in many respects come to be perceived as more important than policy content. Personalities have become as important as issues. Party “spin doctors” hold powerful positions.

In the Introduction to this book I argued that global systems of communication have to some degree compressed time and space. In other words movement and communication across space is more fluid. It is now possible, for example, for millions of viewers around the world to view the same live instantaneous broadcast. However, I would not want to exaggerate the extent to which boundaries have dissolved. Time–space compression is experienced differently by various social groupings and it affects places in different ways. Here Doreen Massey’s notion of “power-geometry” is useful (Massey 1993). Massey uses the term “power-geometry” to describe how individuals and social groups have different degrees of power and control in relation to communication flows and movements. Politicians and journalists in the wealthy Northern hemisphere, for example, typically have much greater opportunity to turn power to their own advantage compared to poor labourers in the Southern hemisphere. Of course the media form only a part of the processes of globalization, but nevertheless they play a central role in lubricating consumerist ideologies.

Media theory

The media, then, are at the heart of processes of political negotiation. In my view they provide us with the frames with which to assimilate and structure information about a whole range of social problems and issues. Judgements concerning the newsworthiness of items reinforce dominant power relations and perceptions of order (see Ch. 2). Those stories that are selected are likely to resonate with existing stocks of social and cultural “knowledge”. And at the same time the news media play a part in shaping future cultural referants (Negrine 1989). Far from the political system being external to the news media, it is deeply bound up with it through a complex web of influences.

Any consideration of the role of the news media in pressure politics hinges upon the issue of media effects. Before moving on to consider how concern over particular social issues is mobilized, I want to look briefly at how mass communications theorists have conceptualized the role of the media in relation to audience effects. The history of media research can be broadly divided into three main periods: the effects tradition, the uses and gratifications paradigm, and critical theory (see McQuail 1991).

The effects tradition

The first major period was between roughly 1900 and 1940. The earliest theories of media effects viewed the audience as highly susceptible to manipulation and propaganda. The European “mass society” tradition was highly critical of moves towards mass education and the development of the press. The theory was not based upon empirical research but anecdotal evidence of the increasing influence of the media in people’s lives. Although mass society theory has greatly influenced modern European social and political thought, it was based upon a simplistic view of the audience. Typically people were seen as a homogeneous mass of damp sponges, uniformly soaking up messages from the media. It failed to account for the sheer diversity of interpretations that could be drawn by different subsections of the population.

Modern communications theory can also be traced back to another major influence; that of the “hypodermic model”, which became popular in the USA following the emigration of members of the Frankfurt School during the early part of the twentieth century. Again this theory was not grounded in empirical research and it treated the audience as though it was in a social and historical vacuum. The audience was conceived of as essentially passive; the media simply injected messages into the audience like a syringe and individuals responded in a predictable way.

Uses and gratifications

Both mass society theory and the hypodermic model were challenged during the 1940s by the rise of a new commercially oriented approach to the media in the USA. This became known as the “uses and gratifications” approach and dates from approximately 1940 to 1960. In contrast to earlier theories, it was based upon empirical research into the ways in which people use the media. The audience were rightly viewed as active receptors who were selective about the information they received from the media. For example, Katz and Lazarsfeld’s (1955) “Two-step flow” model implied that the effects of the media on the audience were limited, while the social and cultural contexts in which communication took place were of great importance. Rather than viewing the audience as a mass of atomized individuals, they recognized that individuals were members of social groups and that responses to the media are mediated through these networks. Thus media were seen as having an indirect rather than a direct influence. However, this paradigm was based upon a liberal-pluralist conception of the media in society and overemphasized individual autonomy. The liberal-pluralist position makes a number of basic assumptions. First, it assumes that having a diverse range of newspapers and broadcasting outlets ensures that different points of view can be given adequate representation. However, in my view, the assumption that all interests can be adequately represented has long since ceased to stand up to critical scrutiny. Second, the theory suggests that we have a free press that is not controlled by the state. Private ownership of newspapers is seen as guaranteeing editorial independence. Third, it maintains that consumers have ultimate sovereignty since they can always switch to another channel or purchase a different newspaper. If a particular point of view is not represented in the press this is seen as reflecting the fact that it does not have enough support among the public. Finally, I think it overplays the extent to which public opinion is formed through a rational process.

In recent years this traditional perspective has come under increasing attack. In particular, it failed to recognize the ideological character of the informational role of the media; that a number of social and political groups are competing with one another to influence media agendas, and some versions of reality privilege the interests of one section of society over another.

Critical theory

Finally, the third major phase of mass communications research dates from the 1960s to the present day. A number of critical approaches to the North American effects tradition have been developed by British and European scholars. These perspectives can be broadly located within the Marxist school of thought although they encompass a very wide range of thinking. Rather than being concerned with the question of effects, up until present times critical research was largely preoccupied with the processes of production and content and with the concept of ideology (Fejes 1984). The critical school of thought attacked the idea that the media have minimal influence. Theorists such as Stuart Hall (1977) and Stanley Cohen (1972) built their models around the premiss that the media play a central role in the reinforcement of ruling-class ideology, although there was disagreement as to the precise nature of the ideological role of the media and their relationship with the wider social structure. Three main strands have emerged within the critical theory of mass communications; the political economy perspective, the structuralist approach and cultural theory (Curran et al. 1982). However, there are a number of different variants on these approaches, and a significant degree of convergence.

First, the political economy perspective suggests that the workings of the media need to be understood in the context of their economic determination. This strand of theory focuses upon ownership and control of the media, and the impact of commercial imperatives. Researchers such as Murdock & Golding (1977) argue that the media produce a false consciousness that legitimates the position and interests of those who own and control the media. Thus studies within this tradition place more emphasis upon the economic structure of the media and production processes, than on ideological content (for example, Garnham 1986, Halloran et al. 1970, Murdock & Golding 1974). The complexity of the exact mechanisms through which economic factors shape media messages is acknowledged. However, this strand of media theory has tended to be primarily concerned with macro structural influences. Until relatively recently, little work has been carried out into micro-relations, such as the relationship between journalists and their sources. As Curran et al. (1982: 20) observe,

… the macro-level at which the “political economy” analysis is conducted leaves some micro-aspects of this relationship unexplored. In particular, questions concerning the interaction between media professionals and their “sources” in political and state institutions appear to be crucial for understanding the production process in the media.

Structuralism forms the second major strand of media theory This collection of diverse approaches is primarily concerned with forms of media representation and signification, through the analysis of media texts such as newspaper articles, television programmes or photographs (Curran et al. 1982). The concept of ideology is central to structuralism and many studies in this tradition have applied Althusser’s concept of ideology to the study of semiotics (cf. Althusser 1965). This approach was most notably associated with Stuart Hall and colleagues, at the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, during the 1970s. Clearly, it was a move forward from the idea that media texts mirror reality, but there were tensions between the fusion of the economic determinacy of Marxist theory and linguistic theory concerning the structure of texts. Cultural theory developed, in part, as a response to structuralism’s deterministic assumptions and its failure to consider socio-cultural factors.

Finally, in contrast to the above approaches, culturalist studies of the media tend to be more preoccupied with “lived traditions and practices”, and with micro-level aspects of news production processes. As its label suggests, the concept of “culture” occupies a key place within this paradigm. This strand of theory views media institutions and cultural practices as bound up in a complex web of interrelationships. Cultural theorists (for example, Corner 1986, Hoggart 1957, Johnson 1986, Williams 1974) rightly view social phenomena as being determined by much more complex factors than purely the economic infrastructure (cf. Curran et al. 1977). They distinguish between “public” and “private” types of cultural production and consumption and suggest that a variety of different “readings” can be made of texts. For example, Morley (1983: 117) maintains:

To understand the potential meanings of a given message we need a cultural map of the audience to whom that message is addressed – a map showing the various cultural repertoires and symbolic resources available to differently placed sub-groups within that audience. Such a map will help to show how the social meanings of a message are produced through the interactions of the codes embedded in the text with the codes inhabited by the different sections of the audience.

In a classic study, entitled Policing the crisis, Hall et al. (1978) sought to blend a culturalist approach with structuralism. This interesting account of the moral panic over “mugging” explores the mechanisms through which the state attempts to manage the ongoing crises of legitimacy and economic difficulties associated with advanced industrial society. Central to Hall et al.’s approach is the concept of class-biased ideology, or “hegemony”. The notion of “hegemony” (associated particularly with the theoretical work of Gramsci) suggests that the news media present us with a very narrow view of the world which upholds the interests of the dominant class. According to this perspective, although differing points of view are given some expression, “establishment” opinions are invested with greater significance. This is seen as an inevitable feature of the news production process rather than resulting from a direct conspiracy between the media and the state. Rather than ideology being forced upon the populace, this view suggests that control is achieved more subtly through gaining the voluntary consent of the subordinate classes.

There is abundant evidence to suggest that journalists are socialized into their own particular newsroom culture where many judgements are taken as “common sense” and rarely questioned. Moreover, as we shall see later on, institutional voices tend to enjoy advantaged access to the media. In contrast, relatively powerless members of the public, or representatives of anti-establishment political organizations, tend to have a much more difficult task in securing favourable coverage on their own terms (Golding & Middleton 1982).

Marxist challenges to the liberal-pluralist concept of power partly led researchers to review the role of the media and to recognize the importance of studying media institutions and the actual processes involved in the production of news (for example, Tunstall 1971, Murdock 1982, Schlesinger 1987). This sort of analysis, which locates the media within the wider context of the political structure, without assuming determinism, is one of the most promising recent developments. Recent approaches have increasingly recognized that the process of manufacturing consensus is complex, and there has been a degree of convergence between liberal-pluralist and Marxist thought (cf. Schlesinger 1990).

Conceptualizing the role of the media

The problem of determining media effects

Despite decades of empirical investigation into media effects little consensus among researchers has been reached about the long-term impact of, for example, television violence on real-life aggression or political campaigns on voting behaviour. McQuail (1991: 251) observes: “The entire study of mass communication is based on the premise that there are effects from the media, yet it seems to be the issue on which there is least certainty and least agreement.” In some ways this is relatively surprising since media effects are often taken for granted at a common sense level. However, one of the major problems is that it is difficult, if not impossible, to isolate the role of the media from other major social influences such as the education system, the peer group or religion. I think it is all the more complicated with deeply contested issues that may invoke powerful emotional responses. Also, it makes little sense to generalize about “media effects” when research suggests there are important variations between and within the media.

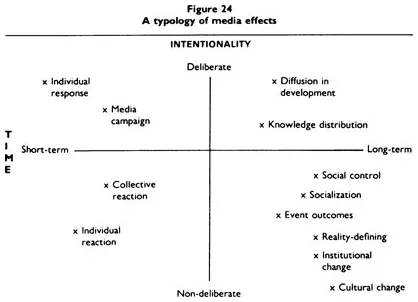

Much depends upon how “effects” are defined (McQuail 1991). Effects may be short term or long term. They may be temporary or relatively permanent. Effects can be measured in terms of direct behaviour change among individuals. Or media can be said to have affected individuals more subtly through acting as a catalyst. Effects may be intended as part of a planned campaign or they may be unintended, resulting from inbuilt biases within the news-making process. Media may reinforce existing attitudes or contribute to new knowledge or opinion. Finally, media may play a part in producing collective hysteria following, for example, food scares over salmonella in eggs or BSE (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 A typology of media effects. Source: McQuail 1991: 258.

Perhaps one of the most striking ways in which the news media exert an individual and collective influence is through “agenda-setting” (see for example Allen & Weber 1983, Benton & Frazier 1976, Gormley 1975). The term “agenda-setting” was first used by McCombs & Shaw (1972) to refer to the process by which issue hierarchies are mediated to the public through election campaigns. From this perspective the news media may not tell us what to think, but they present us with a range of issues to think about. On any typical week day there is a remarkable amount of consensus among the news media concerning prominent lead items. A number of studies ha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Pressure politics and the news media

- 2. News production

- 3. The environmental lobby

- 4. News and the social construction of the environment

- 5. Contested ground: news sources and the media

- 6. Mediating the environment

- Conclusion

- References

- Index