![]()

In its early history, technical analysis dominated the field of risk assessment and analysis, despite the fact that the study of natural hazards dates all the way back to 1946 when Gilbert F. White (White 1946) published his Ph.D. dissertation entitled Human Adjustments to Floods.

But the modern risk analysis really begins with nuclear power. In the so-called Rasmussen Report, the Reactor Safety Study, WASH-1400 (US Nuclear Regulatory Commission 1975), a NRC panel enumerated the estimated probabilities for different accident scenarios. This set off a plethora of risk assessment probes, in which some 15–20 large-scale assessments were completed. These studies set the early agenda for risk assessment thinking and analysis. Risk assessment came to be understood as a process in which hazard identification, exposure assessment, and dose-response analysis provided the risk analysis needed for sound decision-making of the safety of envisioned new technologies. Over time, this approach became enshrined in the so-called Red Book (National Research Council 1983), which rapidly became and still enjoys widespread use in the US Federal agencies of Government and prominent leading private corporations.

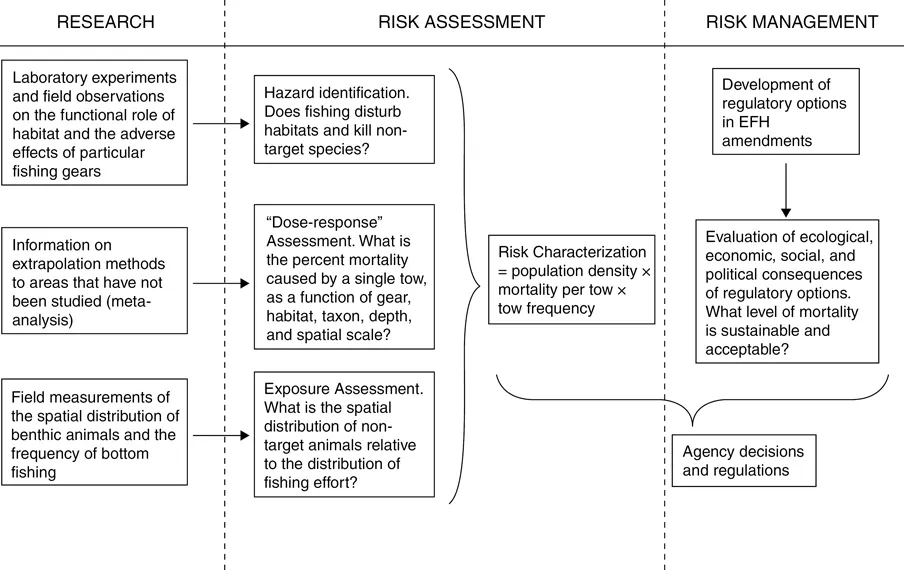

This analysis concentrated on technology and the potential for accidents. The Red Book, in simplified versions, sees risk assessment and management as clearly different tasks. Risk assessment, in this view, is a scientific job. Risk management is where values and the public come in. There is a clear division of labor. And so the risk assessment task is as described in Figure 1.1.

In effect, let’s be clear, publics have little role prior to risk management decisions where they are part of the risk management process only. This has formed the basis for much of US thinking and underlies the so-called deficit model, and is still the bible of most corporations and federal and state agencies.

Because of its widespread adoption and use by federal agencies in the US Government and by major corporations and its understandable embrace by all private sector corporations and state governments, the deficit model deserves attention in the history of risk analysis. The Red Book process, widely adopted and still paramount, was as follows:

There was not much debate about this projected framework of analysis. It was assumed to be looking forward on what a risk analysis perspective might set forth and do.

So a few questions. But then in the 1980s, extensive research showing that experts and broader publics might hold widely different perspectives (Slovic et al. 1980), culminated in the so-called Orange Book (Stern and Fineberg 1996).

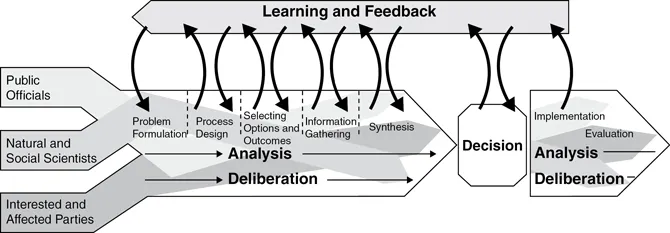

The so-called Orange Book took the Red Book view account of the wisdoms set forth beyond the Red Book, but took the second step of enlarging the notion of risk. So while due respect was paid to expert assessment for technologists, a broader perspective was set forth as indicated in Figure 1.2, with associated discussion as follows:

Assessment, it was appreciated, was needed to address a larger panoply of risk. Appreciating that experts and publics may have different conceptions of risk, the Orange Book conceived of risk as an amalgam of expert judgments of technological risk, and what may go wrong with technological practice, including events at the outer spectrum of uncertainty (such as the giant tsunami at Fukushima), as well as ongoing risks that are unassessed by technical experts (since they are beyond the domain of technology, such as community and local institutional effects).

But life has gone on. Spending several years in Europe (four in Sweden, two in Denmark), with numerous visits to other European risk centers, has shown us that things are often quite different in Europe and the US. In Europe, much attachment has been made to setting aside social science theory and concentrating on what bottom-up assessments of publics might reveal. Social science in the US, it is often claimed, is unduly positivist and an outgrowth of existing social science theory. European analysis, it is claimed, should be fresh, and bottom-up by comparison. This is very much in the French tradition of social science.

And so there is active debate and disagreement. What risk should we be addressing? The natural hazards analysts point out that there is continuing neglect of hurricanes, earthquakes, drought, and other environmental changes. And so climate change assumes even greater importance. The recent analysis of risk assessment by the US National Research Council to improve risk analysis concludes that risk assessment is at a crossroads and its value and relevance are increasingly questioned (National Research Council 2009). And the major thrust of concern relates to the deficit model. The fact is that stakeholders possess much of the relevant needed knowledge – will it be accessed and brought into an integrated assessment? And resilience thinking introduces a broader measure of considerations – how should preparation best proceed? How may adaptation take account of the dynamics of change in human-environment systems? What do we learn from Gunderson and Holling about the cycles of change and dynamics of change in Panarchy? (Gunderson and Holling 2002). And what role does social capital play, as outlined by Robert Putnam in Italy? Social amplification studies call attention to “ripple effects” in consequences. We often externalize them in risk assessment – something even beyond thinking in the Orange Book. How does this affect how we address the risks that matter and must be assessed and internalized in any serious framework of analysis?

What goes on in the natural hazards community of analysis is also important. Natural hazards are almost always underestimated – at least in probabilities. Kunreuther (2015) has found that ordinary people may buy insurance against floods or earthquakes, but if events do not occur soon, insurance payments are cancelled. We seek security against natural disasters but timeframes are short in seeking confirmation. Why waste money on insurance if events do not happen?

Technical experts versus publics

Years ago, Baruch Fischhoff (1995) wrote perceptively that to access risks properly we “must get the science right” and “we must get the right science.” And so, despite occasional social science claims, it is important that in appraising risks that what scientists, engineers, and technologists bring is essential for understanding risks. As an example, the legion of studies on nuclear accidents is essential for technology design, worker training, and the selection of evacuation zones and needed domains for risk communication.

But that type of knowledge is usually there. What is not there is a larger conception of hazard and risk. Elsewhere we have defined hazards as “threats to people and what they value” (Kates et al. 1985). The second part of this is important and a continuing issue of debate. Science and technology assessment provides part of the puzzle. But there is more. The second part of the hazards – threats to values – is also important. And we found out from nuclear power that process issues and threats to civil liberties (values) are also important. But that surfaces a larger issue – risk is not only about potential harms to persons (health effects) but also involves disturbances on nature, communities, and other things people value. As the social amplification approach to risk has made clear (Pidgeon et al. 2003), risk consequences affect communities, institutions, and identity. These are not easy issues but must be addressed. And then there are “ripple effects” – those effects of risk beyond the immediate locality. People, institutions, and economy beyond the local scale might be affected. They need to be considered, so a full risk assessment goes beyond the usual harm to people in their physical being. How are communities affected? And what about suppliers in supply chains beyond local businesses? They are all part of the story.

So how does this relate to the risks we should work on? The traditional view, the deficit model, is that publics are uninformed, emotional, and prone to NIMBY attitudes. Analyses of NIMBY have universally rejected the simplistic thinking assumed, and the propensity to let others take the risks, whatever they are. But experimental studies at Decision Research and elsewhere have destroyed this simplistic view. Rather what they have shown, in considerable detail, is that publics assess risks very differently than experts, but they are quite rational in their view. Pushed farther, this evidence makes clear that scientific/technical assessments are part of the story of what risks matter, but only part of the story. Such assessment is an important piece, but only a piece of a robust assessment. It can be viewed as overly narrow and in that sense, if taken to be the base of risk decisions, irrational in its own way. Nonetheless, the Red Book remains the bible of US federal agencies, with publics only involved in the final stage of risk management, and not in assessment, even though they are experts on risk to societal values and to local communities.

But thinking about risk assessment and the risks that merit attention has gone on. So the so-called Orange Book has built on the thinking during the 1980s and 1990s but taking another jump. As Figure 1.2 shows (see above) early public engagement with risk management is not only about improving the process of public support and engagement and the creation of community consent but also drawing in that expertise often missing from risk assessment and laying the base for guiding what risks to work on which, in the end, matter less.

Values: What do we know about them? How do they enter in?

If hazards are threats to people and their values, we have done much on the first and little on the second. But this is no easy matter. One the one hand, the concern over threats to civil liberties played a significant role in public concern about nuclear power. But values are obviously a complex matter. Risk perception studies show substantial anchoring of perceptions and concerns in social values. But few studies have explored the linking of perceptions to values. An early exploration was Von Winterfeldt (1992) who defined an array of values that entered into and drove perceptions. Then Douglas MacLean, a philosopher, explored these values in some depth (1982).

The value issues that have received greatest attention have been in the natural hazards domain, namely identity with place. In 1992 Ralph Keeney built on this in his Value-Focused Thinking: A Path to Creative Decision-Making. More recently, Gregory et al. (2012) have extended this discussion and indicated how value issues can be incorporated in addressing decision problems with some guidance, notably

•develop a complete understanding of what matters and structure these into explicit objectives;

•include things that matter whether they are easy to measure or not;

•distinguish clearly between means and ends;

•develop alternatives to meet multiple objectives. Invite people to develop relevant alternatives.

(Gregory et al. 2012)

Values and culture: What are the links?

Risk in one place is often not risk in another. There are many reasons for such discrepancy, which we explain at some length. But risks differ with cultures. As Douglas and Wildavsky (1987) have shown, culture structures not only the risks of concern but even what people eat and avoid. Subsequent studies (Rayner and Cantor 1987) have posited a quadrant of various cultures.

It should be noted that the dominant perspective in public perceptions and concerns over risk has clearly been the psychometric paradigm, as developed particularly by Slovic and Fischhoff. But the cultural perspective affords additional insight. Subsequent studies by Rayner and Cantor have shown that political culture has far-reaching effects on public perceptions and the processes used for ranking societal decisions. A clear example is that of GMOs where US science has affirmed, according to usual perception, the basic safety of GMOs. In Europe, by contrast, a broader conception of risk has inquired into effects upon various animal species and nature written broad. And so what has been a non-issue for American regulatory groups and corporate entities has become a major issue of debate in Europe.

But political culture raises broad issues. Putnam (1993) in his analysis of political culture changes in southern and northern Italy shows clearly how changes in social capital produce changes in social culture. Such change has far-reaching effects on democratic procedures and levels of political engagement. And in the end, they shape what democracy can be. All this is directly related to governance and risk, and what may happen.

Emotions. Emotions also play an important role in public response, as Slovic (2010) has recently shown. While much of past work, including that of Slovic and Fischhoff, has centered upon cognitive issues in risk perception and responses, recent work has shown ...