![]()

1 Introduction

Jargon busting

Learning a new subject is made much harder when you are faced with a barrage of acronyms. On the other hand, continuing to use the full name makes life difficult too. To get everyone on the same starting line, let's learn the acronyms right at the beginning:

Table 1.1 Acronyms.

| EA | | Equality Act |

| DDA | | Disability Discrimination Act |

| EHRC | | Equality and Human Rights Commission |

| SEN | | Special Educational Needs |

| SENCO | | SEN Co-ordinator |

| CRB | | Criminal Records Bureau |

| SEND | | SEN and Disability (Tribunal) |

| IPSEA | | Independent Parental Special Education Advice |

| DED | | Disability Equality Duty |

| DES | | Disability Equality Scheme |

Appreciative inquiry

This is the name of an approach that looks at issues in a different way. It asks us not to look for what is broken and fix it, but rather to look at what works. We approach our schools with an appreciative eye. It's not about looking at what we do through ‘rose-tinted glasses’ but about recognising our achievements.

For example, suppose you receive the results of a survey that was designed to assess parental satisfaction. It says that 94 per cent of your school's children's parents are happy with the service you provide. What would you normally do? You may decide to interview the 6 per cent that are unhappy. Appreciative inquiry says that you should ask the 94 per cent what you did to make them happy.

It is easy to view this as a rather simplistic way to face the school's biggest challenges, but it is also easy to be cynical and dismissive of this approach. We should encourage a working environment of appreciation of what works, which will then lead to a positive shift in attitudes. At the end of your next meeting, try asking this simple question: ‘What did we do well in this meeting?’

As you read this book, remember all the good practices your school already has. Remember the successful outcomes you have achieved for all your pupils with SEN and disabilities, no matter how small these might have been. Use this information to performan appreciative enquiry into your inclusive practice, as these will be your building blocks for future successful outcomes.

History of disability legislation

From October 2010, the Equality Act (EA) came into force. This book explains how the EA applies to those providing education in schools. It provides examples of how the duties work and suggests some simple approaches that may help to ensure that children with disabilities are not discriminated against.

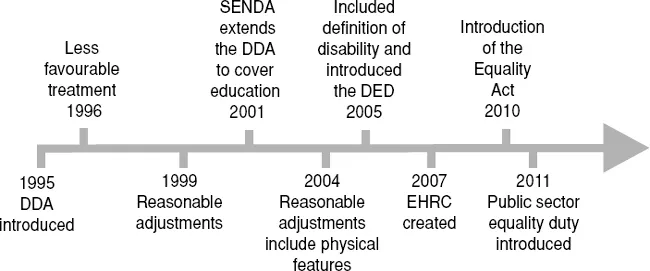

The largest single change in disability legislation happened when the Disability Discrimination Act was introduced in 1995. This made it unlawful to discriminate against people in respect of their disabilities in relation to employment, the provision of goods and services, education and transport. In addition to imposing obligations on employers, the Act placed duties on service providers and required ‘reasonable adjustments’ to be made when providing access to goods, facilities, services and premises.

In 1996 it became unlawful for service providers to treat people with disabilities less favourably for a reason related to their disability (termed ‘Less Favourable Treatment’). In 2001, the Special Educational Needs and Disability Act extended the DDA to cover education. In 2003, people who are registered as blind or partially sighted were automatically deemed as being disabled for DDA purposes. In 2004, part 3, which deals with organisations offering services, was amended to ensure service providers made reasonable adjustments to physical features of their premises to overcome barriers to access. In 2005, the scope of the DDA was extended to cover people with HIV, cancer and multiple sclerosis.

The Disability Discrimination Act 2005 brought in the Disability Equality Duty for all public authorities. In addition, specific duties, which include the development of a disability equality scheme, apply to some public authorities. Public bodies and local authorities are included in the specific duties. These duties apply to the provision made by organisations and local authorities but also need to be taken into account when organisations and local authorities procure goods and services from other agencies to whom the duties may not apply; for example, where service provision is run by a voluntary organisation or a private company.

Figure 1.1 Timeline of recent disability legislation

In 2007, the Disability Rights Commission was subsumed into the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC). The EHRC has powers to issue guidance on and enforce all the equality enactments (covering race, sex, disability, religion and belief, sexual orientation and age).

In 2010, the Equality Act was introduced, which combined discrimination and equality law for race, sex, disability, religion and belief, sexual orientation and age into one single act.

A new fundamental principle

The Disability Discrimination Act 1995 departed from the fundamental principles of older UK discrimination law (the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 and the Race Relations Act 1976). These acts depended on the concepts of ‘direct discrimination’ and ‘indirect discrimination’. However, those concepts were deemed insufficient to deal with the issues of disability discrimination. The core concepts in the DDA 1995 were, instead:

• ‘less favourable treatment’ for a reason related to a person's disability;

• failure to make a ‘reasonable adjustment’.

‘Reasonable adjustment’ is the radical concept that made the DDA so different. Instead of ‘indirect discrimination’, where someone can take action if they have been disadvan-taged by a policy or practice, reasonable adjustment is an active approach that requires employers, schools and service providers to take steps to remove barriers from participation by disabled people. The concept is retained in the new Equality Act.

Models of disability

Trying to understand human intelligence has been a preoccupation of many scientists and psychologists since antiquity. There is nothing new in trying to pigeonhole people, whether it's the way we dress, where we live or what our political persuasion might be. The need to identify who we are and what we are capable of is part of being human. We all have labels given to us whether we like it or not — fat, slim, black, white, clever or stupid. Putting people into groups is a very human practice, but when labelling becomes a matter of political policy, when those labels stop you from fulfilling your potential in life, when doors are closed to you due to unfair and biased labelling, then it is time to reassess and account for our attitudes and open ourselves up to new ways of thinking.

The medical model of disability

The medical model promotes the view of a person with a disability as dependent and needing to be cured or cared for, and it justifies the way in which people with disabilities have been systematically excluded from society. The person with the disability is the problem, not society. Control resides firmly with professionals; choices for the individual are limited to the options provided and approved by the ‘helping’ expert. The medical model, naturally enough, concentrates on disease and impairments. It puts what is wrong with someone in the foreground. It is concerned with causes of disease. It defines and categorises conditions, distinguishes different forms and assesses severities.

Figure 1.2 Labels.

However, there is a place for the medical model in school, and that is to help understand a pupil's medical needs, i.e. medication and emergency procedures. It should not be used to predict how the child will fare within the school environment.

The medical model is sometimes known as the ‘individual model’ because it promotes the notion that it is the individual person who must adapt to the way in which society is constructed and organised.

Powerful and pervasive views of people with disabilities are reinforced in the media, books, films, comics, art and language. Many people with disabilities internalise negative views of themselves that create feelings of low self-esteem and achievement. The ‘medical model’ shows people with disabilities in a negative light and creates a cycle of dependency and exclusion, which is difficult to break. The ‘medical model’ thinking often predominates in schools where special educational needs are thought of as resulting from the individual, who is seen as different, faulty, and needing to be assessed and made as normal as possible. If people were to start from the point of view of all children's right to belong and be valued in their local school we would start by looking at what is wrong with the school and the strengths of the child.

What is unhelpful about the medical model?

It is likely to inspire pity or even fear. Pity is not a useful emotion. Many people are scared of impairments, sometimes irrationally so. The medical model risks objectifying people, lumping them together because of their condition, not because of who they are. Perhaps the most important consequence of the medical model is that bringing the impairment into the foreground risks pushing the person into the background. They become less of a person and more a collection of symptoms. What is more, it doesn't have very much to say about people's lives and how they live them.

The social model

This second approach is based on the social model of disability. The social model of disability is a different way of thinking about disability. It is often said that a big part of the battle to overcome the barriers faced by people with disabilities has to do with changing ‘hearts and minds’. The idea is to replace old-style thinking with a very different perspective. The aim is to help people to see the person first, not the disability. That helps remove much of the fear and anxiety that people have about disability, and can clarify what changes need to be made in...