![]()

1

Terms and Motives

Rooted in past centuries, town and terraced housing was a product of necessity, since building in dense urban settings forced land-use efficiency. Similar to other housing prototypes, they migrated, along with their builders, and replicated elsewhere. Their key architectural features—small footprint, tall, attached—remained a continuous attraction. Contemporary social, environmental, and economic realities are once again turning interest to this design. This first chapter defines and clarifies principles and terms associated with townhouses and describes their relevancy to our times. Throughout the book the prototype will be referred to as a “townhouse.”

Defining Characteristics of Townhouses

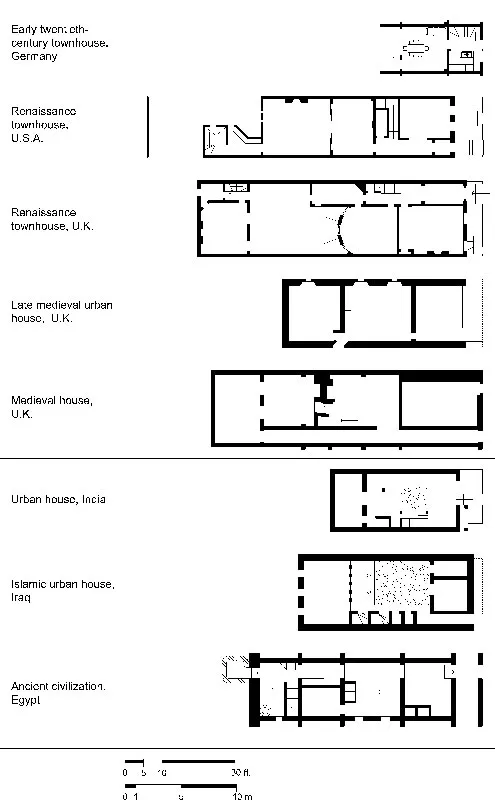

Townhouses were originally defined by Vitruvius in the first of his Ten Books on Architecture as “any home in the town.” Constructed to house many people within the city walls, they were low-rise, ground-related, attached units built in rows or blocks. According to Gorlin (1999), contemporary townhouses evolved from their ancestors in ancient Rome, the London house and the French hôtel particulier (Figure 1.1).

1.1 Selected examples of ground-floor plans of townhouses in various regions and times

Townhouses share a common wall and are often formed by a repetition of recurring units, made into a single assembly through their continuous façade. Pfeifer and Brauneck (2008) suggest that this repetition fosters “continuity, reliability, stability and homogen-eity,” as illustrated in Figure 1.2. Each structure is characterized by a vertically oriented circulation and a narrow footprint. Their small size allows more units to be built within the same area, thereby increasing density.

1.2 Nineteenth-century terraced homes in London, U.K.

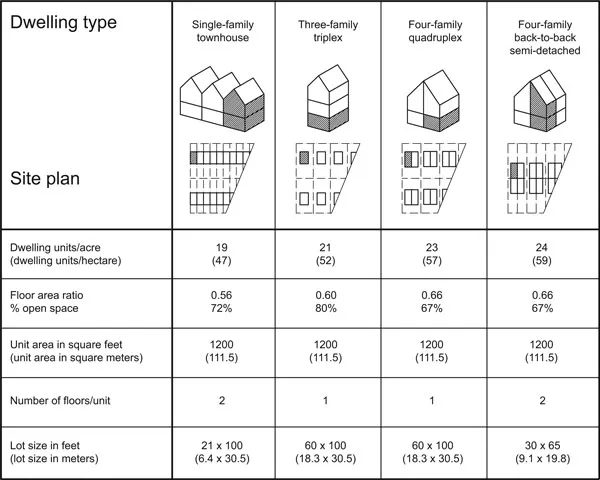

Since their introduction centuries earlier and even more so at present, one of the main attractions of townhouses rests with their ground-related qualities and human scale. Whether used by one or several households, their low-rise design permits easy access to a back and front yard. Unlike apartment living, where a number of occupants share the same main door, exterior space and hallway, townhouses offer independence and privacy despite the elevated density. In fact, according to Schoenauer (1992), townhouses can reach residential densities as high as other multi-unit prototypes without the drawbacks of crowded living, as shown in Figure 1.3.

1.3 Comparative densities between single-family townhouses and multi-family prototypes

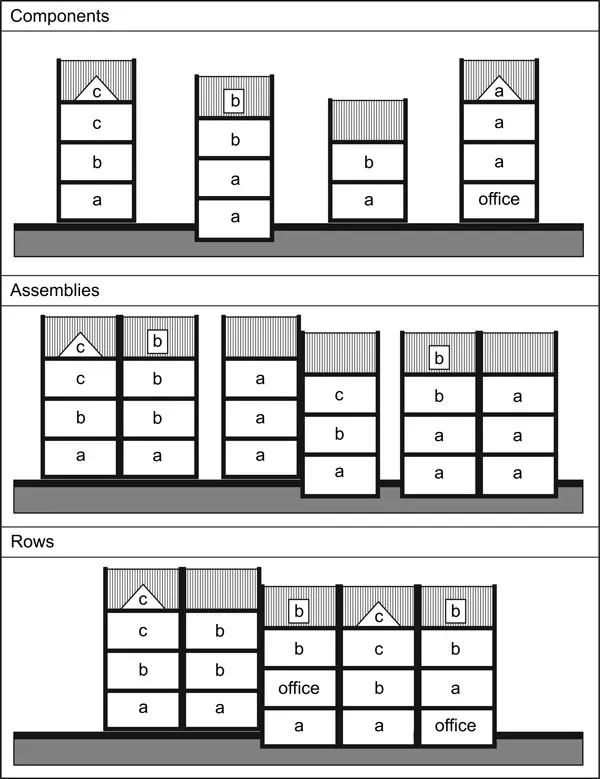

An historic survey shows that a width range of between 14ft. (4.3m) and 20ft. (6.1m) includes most townhouse designs. Reflecting on their narrow widths and parallel walls, Gorlin (1999) suggests that the townhouse is “a typology of enormous restrictions, and therefore a laboratory of creative possibilities within a very limited realm.” Yet despite these constraints, this prototype lets architects design dwellings that, depending on their overall configuration and variety of spatial arrangements, can also define townhouses. The most ubiquitous forms are single-family units placed in rows. When a structure (i.e. one slice of a row) houses two households, it is known as a duplex. A building that houses three families will be known as a triplex. Another option, known as the stuck townhouse, offers savings by placing two two-storey dwellings on top of each other. Units taller than four storeys are rare, since they can lose their ground-related qualities. Some of these variations are depicted in Figure 1.4.

1.4 Spatial vertical arrangements, attachments and ground relations of townhouses (the letters indicate households)

Townhouse units or communities can have various forms of tenure, including freehold, co-ownership and condominium. Freehold tenure is often associated with detached homes, and involves individual propriety of both the unit and the lot. Co-ownership involves a group of residents who share ownership over the units and lots. Condominium tenure, on the other hand, involves individual ownership of the units and shared ownership of the lots and open spaces. Townhouses can take the form of any of the above-mentioned tenures.

Pfeifer and Brauneck (2008) argue that “the city as we know it today does not fulfil the demands we will place on it in the future.” As such, architects and planners have recently been encouraged to investigate smaller housing prototypes and densification strategies. The search for affordable and sustainable dwellings adaptable to changing family needs has led to a renewed interest in townhouses. The following sections will outline those contemporary societal challenges and the possible use of townhouses to address them.

Environmentally Friendly Dwellings

In a society which is becoming increasingly aware of the human toll on the environment, common housing practices are being re-examined to lessen their impact. The proliferation of large detached suburban homes is supporting evidence that, for the first time, local actions have a global effect. Seen from a contemporary perspective, the townhouse can be regarded as a solution to some of the environmental consequences of urban sprawl. They can therefore be viewed as a form of sustainable development, stemming from their high density and resource reduction.

The term sustainable development began to draw public attention beginning in the mid-1970s. An oil shortage sparked interest in reducing energy consumption. The dis-course that followed revolved around how to meet present needs without compromising the ability for future generations to meet their own. Although these needs are largely undefined, they included social equity, fair distribution of resources within and among nations, and the need to resolve the conflict between development pressures and the environment.

The construction of new detached dwellings beyond the urban fringe leads to the decentralization of the urban core through the unlimited outward extension of dispersed development. In many developed countries, extensive use of agriculture and forested land causes damage to the environment, a condition which has been taken as an indication that humanity is stretching the carrying capacity of the Earth to its limits.

Dispersed developments and the suburban lifestyle have also led to a car dependency and the resulting air contamination. Vehicle exhaust is culpable for urban pollution and climate change, as between 70 percent and 90 percent of carbon monoxide emissions come from motor vehicles (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 1995). The elevated density of townhouses cultivates walkable communities on a pedestrian scale and with a public transit system.

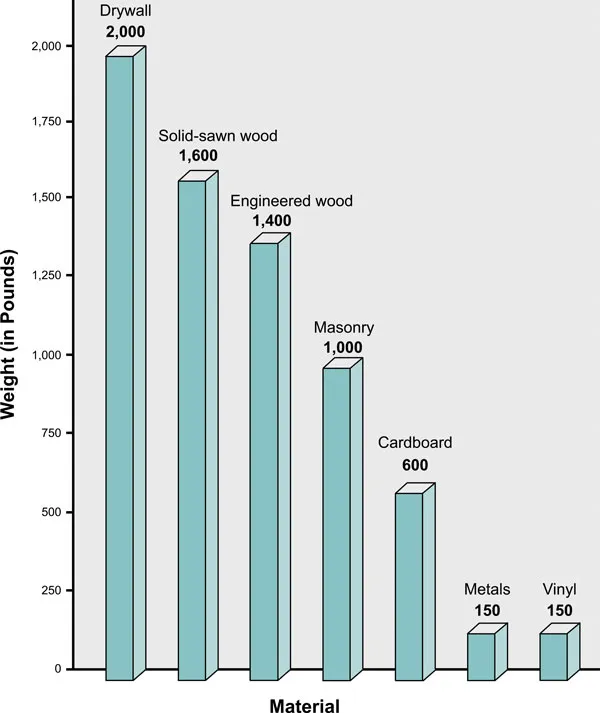

Unfortunately, the damage of urban sprawl on the environment does not stop with automobiles. The proliferation of detached homes also leads to increased waste and overuse of the Earth’s natural resources. One acre (0.4 hectares) of forest is needed to build a 1700 sq. ft. (160 m2) home (Nebraska Energy Office 2007). A 2007 study by the Nebraska Energy Office also demonstrated that, on average, 8,000 lb. (3.6 tonnes) of waste is produced when a 2,000 sq. ft. (190 m2) home is constructed, all of which is shipped to landfills (Figure 1.5).

1.5 Typical amount of waste generated by construction of a 2,000 sq. ft. (190m2) home with brick veneer and vinyl siding

The nature of townhouses results in the reduction of materials used in their construction. While the popular North American wood-frame, single-family detached home contributes to deforestation, the shared walls of townhouses reduce timber requirements. Efficient use of building materials, conservation of water, durability and longevity of building components can be better achieved through the construction of small-footprint, higher-density housing. Grouping homes into rows reduces wall surface by up to 53 percent for units in the middle of a row, eliminating unnecessary building materials. The construction of townhouses results in resource efficiency, both in the construction and operation phases and are, therefore, attractive to a society that has become more aware of the depletion of the Earth’s natural resources.

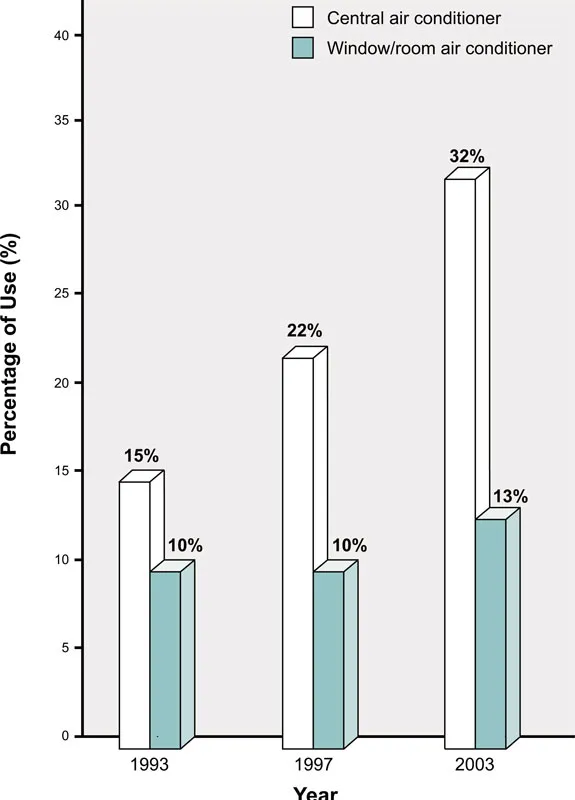

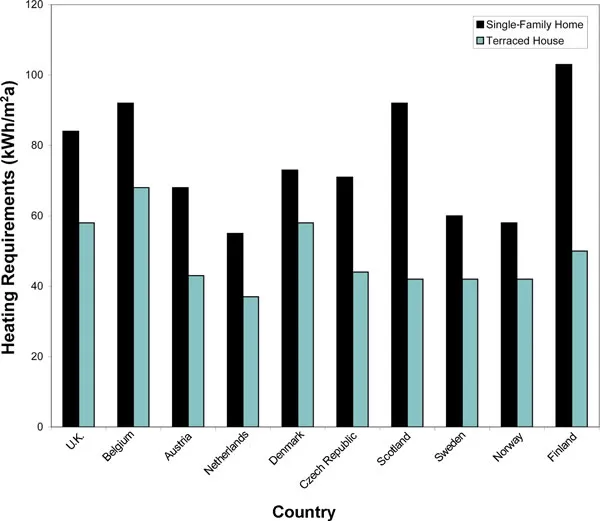

Detached dwellings further lead to increased heating and cooling requirements due to their exposed envelope. Air conditioning, for example, consumes as much energy during one summer season as the yearly consumption of all other appliances combined, and their purchase and use have only increased in recent years (Figure 1.6). The nature of townhouses, exposed to the elements on only two sides, conserves energy. When heat escapes through the common wall of one unit, it is likely to enter an adjacent unit. Grouping units in a row reduces heat loss by 42 percent in the middle units (Friedman et al. 1993). Depending on local climates, townhouses can consume up to 68 percent less energy than detached homes (Figure 1.7) (International Energy Agency 2008).

1.6 Purchase and use of air conditioners in Canada have increased between 1993 and 2003, which is attributed in part to hotter summers

1.7 Townhouses reduce energy requirements by up to 68 percent, depending on local climate as this chart demonstrates

In recent years, governments and construction associations around the world have begun to establish standards for sustainable building practices. These standards go beyond national building codes and set stricter efficiency level criteria, and act as accredi-tation systems. Builders and projects are qualified and distinguished according to the scope of their environmental pursuits. In North America, the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) established the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) (U.S. Green Building Council 2008). The standard in the U.K. is known as Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM). These methods have become a way of developing new building strategies

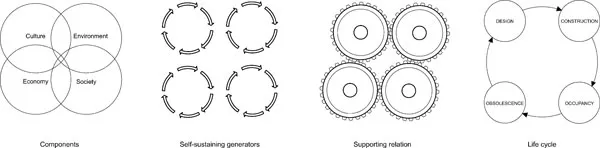

When designing sustainable dwellings, a number of principles, which are illustrated in Figure 1.8, can be considered. The path of least negative impact focuses on limiting both short- and long-term adverse effects on environmental, economic, societal and cultural facets of a development project. For example, townhouses lessen the initial impact of construction through reduced building materials. The long-term effects of a project can be assessed in terms of being a self-sustaining process of resources and activities, such as townhouses reducing energy requirements by including photovoltaic panels. As certain systems become more independent, others can also work in a supporting relationship. While this approach requires an expanded understanding and heightened sensitivity, building smaller houses to reduce urban sprawl and infrastructure costs is a well-known example. Finally, the life cycle approach regards the evolution of successful paths of least negative impact, as the continuity of a system throughout all the phases of its use.

1.8 Principles of sustainable systems

The devastating effects of human activities on the environment have led to fundamental changes in current development patterns, based on sustainable principles. Communities made up of dwellings built in rows can be considered to be cohesive, sustainable developments. These projects encompass features which work together to improve the environment for future generations, such as higher density, reduced land allocation to roads and heightened conservation of energy and natural resources. In the interior, other aspects fall naturally into place, such as an effici...