![]()

PART 1

EXPLORING AND EXPLAINING CRIME

![]()

| |

| | Introduction |

| | The History of Juvenile Crime |

| | Studying The History of Crime |

| | Communities and the Control of Crime |

| | Changing Definitions of Crime |

| | Summary |

Crime – The Historical Context

INTRODUCTION

Crime, criminals and how they are dealt with by society are topics of endless fascination. Look at any newspaper or glance at what’s on television or at the cinema and it is immediately clear that there is a vast and seemingly insatiable interest in crime and criminals. We are interested both in ‘real life’ crime and criminals and in fictional accounts. We could ask why there is so much interest in this area; even if many people break the law from time to time, most people are not involved in spectacular criminality, yet we seem to love to watch and read about it. Maybe such an interest demonstrates a sense of moral outrage and the enjoyment of seeing the wrongdoer punished and justice being done – given that in most fictional crime stories the criminals tend to come off worse eventually. Or perhaps it reflects a sympathy with the underdog and a degree of admiration for those who try to beat the system, with yesterday’s public enemies and villains having a habit of becoming present-day cult figures. Or maybe this interest just demonstrates the excitement and enjoyment gained from reading about and watching that which we ourselves would not engage in – a sort of substituted excitement or vicarious pleasure. Whatever the reasons, murder, robbery, fraud, drug smuggling, gang warfare, rape, football hooliganism and so on make good subjects of conversation and exciting and profitable films. Indeed a visitor from another culture might assume crime was a basic and ever present feature of everyone’s everyday lives. Yet apart from minor law breaking, very few people go on to become professional criminals.

QUESTION BREAK: CRIMINALS AS CELEBRITIES

‘Mad Frankie Fraser’ a notorious (ex)gangster is now a popular speaker at social functions. The following extracts are taken from his own website:

Frank has been a contract strong-arm, club owner, club minder, company director, Broadmoor inmate, firebomber, prison rioter but – first and last – a thief. 26 convictions. 42 years inside. In the 60s Ron and Reggie Kray sought his services but Frank chose to pitch in with Charlie and Eddie Richardson and their South London alleged ‘Torture Gang’.

• List other criminals that have become celebrities.

• Why do you think people admire such criminals?

This interest in criminality has been present throughout history. The briefest scan of the history of literature reveals the central role played by crime and criminals – from the Greek tragedies, to Shakespeare’s Hamlet, to Bill Sykes in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, to George Orwell’s 1984. Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment is a classic work of criminal psychology, while the New Testament story of Jesus tells of wrongful accusation, arrest, trial, conviction and execution.

However crime is not a clear cut or static phenomenon. What was viewed as criminal in the past was often quite different to current notions; just as many contemporary criminal acts would not have been viewed so in earlier times. Indeed in studying crime and punishment over time one of the most obvious ‘findings’ is the relative nature of crime. What is seen as and defined as criminal varies according to the particular social context in which it occurs, as the extracts and questions below illustrate.

QUESTION BREAK: THE CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL RELATIVITY OF CRIME

It is easy to think of examples of behaviour which one society sees as criminal and another as quite acceptable and normal; and there are behaviours which are seen as criminal now but which were perfectly acceptable in previous times. Consider the extracts below and the questions that follow them.

It is easily observable that different groups judge different things to be deviant. This should alert us to the possibility that the person making the judgement of deviance, the process by which the judgement is arrived at, and the situation in which it is made will all be intimately involved in the phenomenon of deviance …

Deviance is the product of a transaction that takes place between a social group and one who is viewed by that group as a rule breaker. Whether an act is deviant, then, depends on how people react to it … The degree to which other people will respond to a given act as deviant varies greatly. Several kinds of variations are worth noting. First of all, there is variation over time. A person believed to have committed a given ‘deviant’ act may at one time be responded to much more leniently than he would at some other time. The occurrence of ‘drives’ against various kinds of deviance illustrates this clearly.

(From H. S. Becker, Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance, 1963, pp. 4–12)

Burning and hanging women as witches was commonplace in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. Witches were believed to have made pacts with the Devil which gave them supernatural powers. They were blamed for all sorts of personal and social misfortunes – illnesses, bad weather, loss of and damage to property.

Although many people associate burning at the stake with witchcraft it was used much less in England than other parts of Europe – particularly France, Switzerland and the Nordic countries. Only a few witches were burnt in England, the majority were hanged, possibly as a cost saving exercise and possibly because the public would not tolerate such a barbaric punishment. Scotland did burn witches and there are at least 38 recorded instances, the last being in 1722.

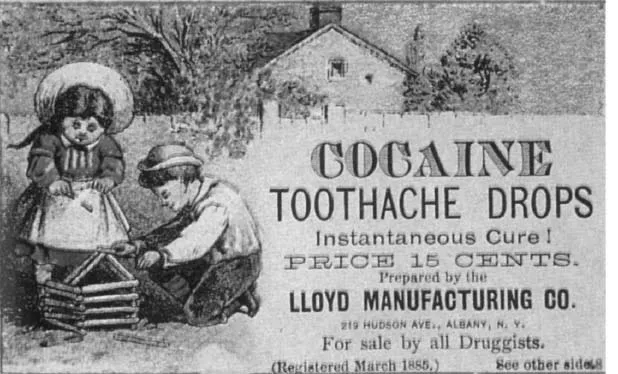

In the late 19th century cocaine was widely used as a pain killer in the USA – much as aspirin is today – and advertised with pictures of children at play.

(From A. G. Johnson, Human Arrangements, 1989, p. 249)

1 Alcohol drinking and bigamy illustrate the relative nature of crime anddeviance.

(a) List other types of behaviour that have been categorized as criminal or deviance in one society but not another.

(b) Give examples of behaviour that has been criminal or deviant at certain periods of time but not at others.

2 In looking at responses to crime and deviance Becker refers to ‘drives’ against certain types of behaviour. What types of crime or deviance have been subject to such drives in recent years in the UK?

The fact that crimes, and the ways in which they have been punished, vary from place to place and time to time highlights the importance of social reaction in determining what behaviour is categorized as criminal. There is no particular action that is criminal in itself – an action only becomes criminal if society defines it as such. So even an action such as killing another person, which, in the form of murder, can be the most serious of crimes in modern society, in many contexts can be quite acceptable. Indeed in some situations killing other people can be seen as heroic and people can be punished for not wanting to engage in killing – conscientious objectors were imprisoned in Britain in the First World War as were those who tried to ‘dodge the draft’ to fight for the US army in Vietnam in the 1960s.

Bearing in mind the relativity of crime and how it is dealt with, it would be useful to consider the history of crime before examining theoretical explanations for it in later chapters. In considering the history of crime we will examine the historical myths and traditions that surround the way in which crime has been and is viewed. Although there is a general awareness that there was horrendous violence and crime in the past, it is a widely held notion that modern, Western societies have become more and more criminal and dangerous places to live in. Given this tendency to think that things are much worse nowadays, we will start our historical overview by considering if there ever was a ‘golden age’, when ‘things were so much better’, when violence and criminality were only a marginal part of everyday life.

THE HISTORY OF JUVENILE CRIME

We will start our account by referring Geoffrey Pearson’s study of the history of juvenile crime (1983). Pearson used literary and journalistic accounts of crime to argue that it was important not to view criminality in modern society as a new or unique problem and to make the point that, when examining the history of crime, an appropriate subtitle would be ‘there’s nothing new under the sun’. Pearson takes issue with the notion of moral degeneracy (of young people in particular), not in an attempt to underplay the problem of violent crime in modern society but to demonstrate that, if anything, it is a continuation of traditions rather than a new phenomenon. He shows that for generations Britain has been plagued by very similar problems and fears that the myth that Britain has historically been a stable, peaceful, law-abiding nation and that violence is somehow foreign to our national character shows little sign of waning.

The most striking aspect of the history of delinquency is the consistency with which each generation characterises the youth of the day and the way of life of twenty years previously. In 1829 Edward Irving is quoted as inquiring, ‘Is not every juvenile delinquent the evidence of a family in which the family bond is weakened and loosened?’. He talks about the ‘infinite numbers of unruly and criminal people who now swarm on the surface of this great kingdom’ (see Pearson 1983). Thus, while hooliganism and delinquency still make news as alarming and unusual, such behaviour is clearly not new.

QUESTION BREAK: JUVENILE CRIME – THERE’S NOTHING NEW UNDER THE SUN

The following quotes are taken from press, political and literary sources; many are taken from Pearson (1983) although some more recent ones have been added. Place these quotes in historical order and suggest when they might have been said. (The answers are at the end of the chapter – but see how many you can locate correctly before turning to them.)

(a) One of the most marked characteristics of the age is a growing spirit of independence in the children and a corresponding slackening of control in the parents.

(b) We have to recognize where crime begins … we must do more to teach children the difference between right and wrong. It must start at home. And it must also be taught in our schools.

(c) Looked at in his worse light the adolescent can take on an alarming aspect: he has learned no definite moral standards from his parents, is contemptuous of the law, easily bored.

(d) The morals of the children are tenfold worse than formerly.

(e) (On the increase in juvenile crime). In many cases they [juveniles] find themselves in a large city without friends, without family ties, and belonging to no social circle in which their conduct is either scrutinized or observed.

(f) Parents failed to instil respect in their children … neighbourliness had broken down in villages, towns and cities. Decades of poor parenting and increasing selfishness have made life a misery for the police.

(g) People are bound to ask what is happening to our country … having been one of the most law-abiding countries in the world – a byword for stability, order and decency – are we changing into somewhere else?

(h) The most characteristic part of their uniform is the substantial leather belt heavily mounted with metal. It is not ornamental, but then it is not intended for ornament.

(i) There seems to be a general corruption throughout the kingdom … the spirit of luxury and extravagance that seems to have seized on the minds of almost all ranks of men.

(j) These people are simply savages, angry, blind and brutal. They are in this condition because of what they have been drinking. They are all so ill-educated or made crude by inadequate civilizing influences in their homes that they seem unable to drink in an acceptable ‘continental’ fashion.

(k) Any candid judge will acknowledge that manifest superiority of the past century; and in an investigation of the causes which have conspired to produce such an increase of juvenile crime, which is a blot upon the age …Is it not [the case that] the working classes have generally deteriorated in moral condition?

Pearson starts his study by looking at contemporary society – and, as the book was published in 1983, at the late 1970s and early 1980s. In introducing his historical account he makes the point that if each generation has a tendency to look back fondly to the recent past, it is sensible to start with present-day society and compare it with the situation twenty or so years previously, and then to compare that generation with its predecessor. Of course, there are bound to be difficulties in comparing different ages and periods – there will be differing definitions of crime and different measuring techniques and, in particular, a lack of adequate records in previous times. Nonetheless, an impression of the style and extent of crime, and of the popular concerns about it, can be gained by looking at contemporary accounts from newspapers and books of the particular period.

As mentioned, Pearson’s study starts with present-day attacks on our ‘permissive age’ by contemporary public figures and ‘guardians of morality’. In March 1982 the Daily Telegraph suggested that ‘we need to consider why the peaceful people of England are changing … over the 200 years up to 1945, Britain become so settled in internal peace’. There were warnings of a massive degeneration among the British people which is destroying the nation. Kenneth Oxford, the Chief Constable of Merseyside, prophesies that the ‘freedom and way of life we have been accustomed to for so long will vanish’. There are numerous instances of such statements from prominent politicians and public figures alleging that contemporary society is witnessing an unprecedented increase in violence and decline in moral standards. Indeed there is a great consistency in the view of Britain’s history was based on stability and decency, and that the moderate ‘British way of life’ is being undermined by the upsurge in delinquency.

QUESTION BREAK: IMAGES OF CONTEMPORARY YOUTH

• How are youth viewed today?

• What words are commonly associated with contemporary youth? (Consider how many of these words are negative and how many positive.)

• Looking back a generation, how would you characterize British society in the 1960s?

• What words would you associate with British youth of the 1960s?

Twenty years previously, however, we can find remarkably similar comments. At the Conservative Party conference in 1958 there was discussion of ‘this sudden increase in crime and brutality which is so foreign to our nation and our country’. The Teddy Boys were arousing similar apocalyptic warnings of the end of British society. The Teds’ style of dress was derived from men’s fashion of the reign of Edward VII, which explains the name of Teddy Boys. Rock and roll was the musical focus of this youth subculture, and the reaction which the Teddy Boys engendered was one of outrage and panic. The press, in particular, printed sensational reports of the happenings at cinemas and concerts featuring rock and roll films and music. A letter in the Daily Sketch (a popular newspaper of the period) in 1956 announced that ‘the effect of rock’n’roll on young people is to turn them into devil worshippers; to stimulate self-expression through sex; to provoke carelessness, and destroy the sanctity of marriage’, while an article in the Evening News of 1954 suggested that, ‘Teddy Boys …are all of unsound mind in the sense that they are all suffering from a form of psychosis. Apart from the birch or the rope, depending on the gravity of their crimes, what they need is rehabilitation in a psychopathic institution [sic].’ This reaction w...