- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Using play as the method against which all others are compared, this book presents the strengths and weaknesses of different models of teaching, examines various methods of guiding young children's behavior, and shows how to create and maintain a positive learning environment. Finally, it discusses how to work as a team member in ECE settings.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Early Childhood EducationCHAPTER 1

PLAYING TO LEARN—LEARNING TO PLAY

Play is more than just a pleasurable activity for children; it is also a diagnostic tool that offers valuable clues about each child’s psychological “world.

Hughes

▼ Chapter Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define play, and discuss a variety of historical and theoretical perspectives.

- Explain the learning that takes place during sensorimotor, motor, pretend, and dramatic play.

- Identify general developmental, environmental, and cultural variations in play.

As you think about and apply chapter content on your own, you should be able to:

- Refine and clarify your own views on the definition of play in early childhood.

- Explain to parents and other professionals the role of play in early education.

- Tie play activities directly to learning goals for infants, toddlers, preschoolers, and primary-age children.

“Can I play with you?” “Let’s play school.” “My blocks. She took my blocks!” “This is the bus. This one is you, and this one is me; we’re going downtown.” “Let’s dress up and be firefighters; or astronauts.” “Wanna play checkers?” “Do you play basketball for your school?” “Can you come out to play?” “Here is a game everyone can play.”

Play has many faces. Observe young children engaged in their own pursuits, and you will find yourself observing play. Left to their own devices, nearly all youngsters play, although the activities and devices of play may differ greatly across ages, abilities, cultures, and settings. Infants, toddlers, preschoolers, and primary school children play with items they find indoors and outdoors, with toys purchased in stores and made by hand. They play with adults and with each other. They play in imitation of adult activities, take on the identities of characters in stories, and compete in games and sports. Fueled by everyday experience and powered by imagination, play is an essential element in the daily experience of young children; it is impossible to conceive of a healthy childhood without play.

The language of play is likewise rich and extensive, describing almost every human activity imaginable. Toys, games, and sports. Dolls, teddy bears, blocks, educational toys, games of chance, board games, card games, sports with balls of different sizes and shapes, played alone and with others. Partners, teams, positions, and rules. Taking turns, winning, losing, being a good sport. Pretending, imagining, dressing up. Reclaiming babyhood and extending into idealized and whimsical identities as parents, employees, famous people, animals, and super heroes.

As children play they learn. Infants learn about the properties of objects and interactions with adults. Toddlers and preschoolers learn to represent the real world in play and learn social skills as they play with peers. Primary school children learn to apply rules to their own behavior and learn about cooperation and competition as they play. In this chapter, we explore play as an important context for learning during the early childhood years and present an organizational framework for the study, observation, interpretation and facilitation of play. First, we explore some of the many divergent opinions about what exactly play is, the value and meaning of play in early childhood, and reasons why children play.

WHAT IS PLAY, AND WHY DO WE STUDY IT?

On the face of it, play may not seem to need definition, explanation, or study; most of us would say we recognize play when we see it. Play is often construed by adults as the opposite of work, something we do on the weekends, during vacations, or with children. A more academic understanding of play is critically important to our role as early childhood educators for a number of reasons; although the concept seems very simple, in reality the study of play in all its variations and applications is quite complex.

Play is a meaningful context for learning during early childhood, so knowledge of the development of different types of play provides a foundation for appropriate teaching strategies. The best teaching has been characterized as occurring at the midpoint on a continuum between work and play (Goodman, 1994), especially for young children. Also, children use their most sophisticated developmental accomplishments in play activities, and teachers who understand theories and sequences of play will be better prepared to use play as a context for assessment and instruction of important physical and motor, social and emotional, and cognitive skills. Finally, teachers of young children need strong academic backgrounds in play to be able to analyze problems and provide support for children who have difficulties playing. The content of this chapter can assist early childhood professionals in becoming more successful at appraising children’s developmental status, using play as a framework for teaching, identifying problems, and facilitating learning in all domains.

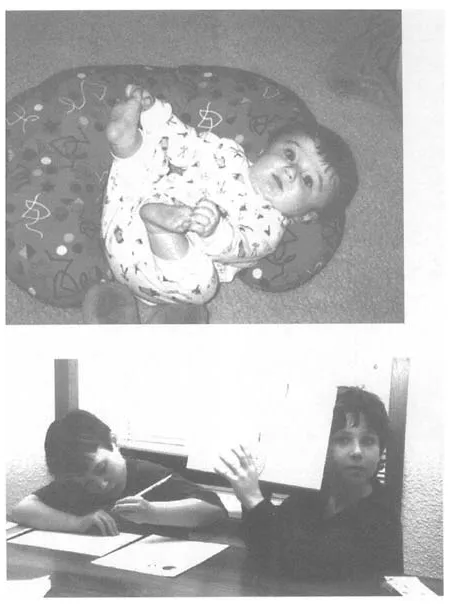

Play seems like a simple concept, but can be difficult to define. Is the baby playing with his toes or exercising his legs? Are the two boys playing school or working on assignments?

Defining Play

Most contemporary definitions of play derive from a list of essential elements proposed by Rubin, Fein, and Vandenberg in 1983. They defined play as active involvement in pleasurable activities that are freely chosen, intrinsically motivated, and carried out as if the activity were real, with a focus on the process rather than on any particular product. This definition conjures up an image of children having fun, busily moving about, interacting with one another or manipulating objects of their own choosing or both, without direction by adults or concern for correctness, accuracy, exacting standards of behavior, or predetermined outcomes. Play that includes all elements of this definition encompasses activities as diverse as object play, imaginary play, and physical games.

The defining elements of play proposed by Rubin, Fein, and Vandenberg (1983) have occasioned some interesting discussions and controversies among early childhood specialists in classrooms and in professional journals, also. Most everyone agrees that the value of play is in the activity itself rather than in any predefined outcomes and that children are intrinsically motivated to play. There is also consensus that play often involves using objects and taking roles in creative, flexible (nonliteral) ways, as when a front step becomes a castle, dirt becomes food, a teddy bear talks, or a dishtowel becomes a cape, and that youngsters engage in these activities as if the activities were real.

Observations of young children suggest that play is more often pleasurable than not, but smiling and laughing, relaxed postures, and positive tones of voice are by no means universal to play activities. Infants often appear to be studying their toys with serious intent as they explore and manipulate, and social games like peekaboo may initially produce fear or distress. Toddlers and preschoolers often recreate events in play that frighten them or cause conflict in real life. Although the fear and anger expressed may not have the intensity of the authentic situation, the imaginary interactions do not always appear pleasurable. Older children often exhibit signs of stress when playing games or sports that require skill or have an element of competition. Do indications of seriousness, fear, distress, or anger during childhood activities mean that children are not playing?

Different opinions also exist about the elements of engagement and external control of play. Parents generally initiate and control the interactions of nursery games until infants have the skills to do so themselves. Preschool teachers often set up scenarios, provide costumes, and specify ground rules for dramatic play centers. Youngsters playing board games or sports have to follow rules inherent to the games. Does the existence of external rules mean that the ensuing activity is something other than play? Older children often appear to replace imaginary play with daydreaming. When children in primary school sit at their desks daydreaming and doodling during free play, are they playing?

The distinction between learning and play may be blurred purposefully in early education settings where play is accepted as a critical component of early learning. Whether play is freely chosen may be difficult to assess in developmentally appropriate preschool classrooms where early childhood teachers go to great lengths to create playbased learning activities. If at a certain time of day children select play activities from a limited number of centers in the classroom, are their choices totally voluntary? If a child makes a game out of an assigned task, is it work or play? Or both? The recognition that play provides both a context and developmental content for early learning raises questions about the exact definition of play and, perhaps more important, is influencing current philosophies of parenting and teaching in Western cultures. In order to place these changes in context, it is helpful to review briefly philosophies of childhood and play throughout history.

A Brief History

Play has recently been described as a universal cultural phenomenon and is also readily observed among the young in all animal species with organized social structures (Hughes, 1999). Ancient writings and artifacts indicate that children have probably always played, although the concept of play has taken on many different meanings throughout the course of history. The adult perspective on play during any given era is preserved in books and stories, illustrations and paintings, and remnants of toys and recreational pastimes that reflect the prevailing notions about childhood. Definitions of play can be seen to vary over time and location, therefore, depending on the meanings play has within the values and beliefs of the culture.

The Greeks and Romans valued games and competition for adults, for example, and art of the period depicts with affection children at play. Childhood seems to have been appreciated as a less serious, more dependent time during which youngsters played both to practice future skills and for immediate enjoyment. During the Renaissance (1300–1600 A.D.), children were seen as imperfect adults, as reflected in European museums’ displays of toys and games from that period that were used in the play of adults and children alike. Play is depicted as a more earnest endeavor, with less spontaneity and more emphasis on adultlike behavior. By the 17th century, there were different toys and games for adults and children in northern Europe but also a growing emphasis on the value of work. John Locke (1632– 1704) wrote of children as “blank slates” who required strict direction and guidance from adults in authority as they developed internal control over their behavior. He focused on play as a mechanism for learning and for encouraging the business of becoming more mature. Although Locke seemed less impressed with the pleasurable aspects of play, he invented educational games and suggested sending kids outside for materials to make their own toys (Locke, 1692/1964). The Puritans brought a similar perspective on play to the United States, emphasizing discipline and learning over fun and games. Children were seen as unruly and unreasonable by nature, needing adults to shape their behavior toward more meaningful spiritual, educational, and vocational pursuits. The emphasis on childhood as a time for learning is reflected in the books designed specifically for the education of children.

In France a generation later, Rousseau (1712–1778) introduced the viewpoint that children are qualitatively different from adults, inherently innocent, affectionate, and playful. He wrote of childhood as a unique period during which play is a natural activity that adults should encourage and observe to better understand children (Rousseau, 1762/1911). Rousseau’s views were also transported across the Atlantic and during the 18th century in the Americas, there seems to have been a range of opinions about play spanning the perspectives of both Locke and Rousseau. A variety of toys, books, board games, and active games indicated acceptance of play as a healthy activity for children; at the same time, parental authority and discipline were evident as important forces in the lives of children. Youngsters were seen as individuals with unique personalities but also were valued as helping hands and working family members.

Scientific approaches by scholars such as G.Stanley Hall (1844–1924) gave rise to the study of child development in 20th-century America. Increased attention to the maturation and learning of children from infancy through early school years was evident in both professional and popular literature of the time. Childhood was studied as a significant period, with particular interest in the role of early experiences in shaping personality and behavior later in life. By the mid-1900s, the results of studies in developmental and experimental psychology were being interpreted and explained in terms of optimal caregiving practices. Publications by influential scholars revealed widely divergent opinions on the value of play. Behaviorists cautioned parents to control children’s environments and use play as a reward for hard work or an opportunity to teach rules of social conduct (Watson, 1928). Developmental psychologists urged parents to encourage and support play as an essential avenue for mastery of physical, emotional, and cognitive abilities (Gesell, 1945).

Theories of Play

Theories attempt to explain why children play and to account for variations in play across children of different ages, cultures, and abilities. Classical theories of play grew out of philosophical reflections on the nature of childhood and the perceived value of playful activities before 1920. These theories emphasized biological, innate aspects of play, using physiological and evolutionary explanations rather than a focus on children’s activities as a point of departure. You will probably recognize the impact that each theory has had on practices in early childhood education, an indication that although none of the theories presented explains play entirely, each has contributed to our understanding of play in the lives of young children.

Play was described early on as a mechanism for discharging surplus energy and releasing tension. This perspective held that children have excess energy to expend and do so during play, especially rough and tumble games. The surplus energy theory underlies assumptions that it is unreasonable to expect young children to sit and attend to instruction or work for long periods and is reflected currently in enduring routines for recess and outdoor play. It also provides an explanation for the fact that adults play less than children do: Growing up means taking on more work (vocational, parenting) and using more energy, thus resulting in less surplus for play. A related theory also viewed work as expending energy but focused on play as a source of renewal (Patrick, 1916). Play, like sleep, was thought of as a way to renew energy resources and provide a medium for avoiding boredom and reviving effort. A remnant of the energy-renewal theory can be seen in home and classroom schedules that alternate work and play or stagger strenuous physical activity with quiet, manipulative play. Another early theory viewed play as an innate mechanism for children to practice the roles and skills they would be required to exhibit as adults (Gross, 1901). Play as mimicry and practice of adult roles is still reflected clearly in preschool play centers that emphasize housekeeping, dress-up, and dramatic play scenarios such as offices, hospitals, schools, and stores.

Theories developed after 1920 are considered to be modern theories of play, developed primarily from observations of children at play as a point of departure. Child development researchers used empirical approaches to collect specific information about play in naturalistic settings. The same methods used at the time to study developmental changes from infancy to primary school were applied to studying individual differences in play due to age, gender, and culture and the relationship between play and developmental status (Fein, 1981; Hughes, 1999).

Innate explanations of play continued to be refined in the 20th century with a shift to theories that included psychological as well as physical hypotheses. Anna Freud (1895–1982) and Erik Erikson (1902–1994) both discussed play from perspectives consistent with their unique psychoanalytic theories. Freud (1974) highlighted the role of power and control over the environment in play and the resulting reduction of anxiety, fear, and guilt, whereas Erikson (1963) underscored the importance of play for building self-esteem by learning about the self, mastering new skills, and practicing culturally appropriate interactions.

After the mid-1900s, innate theories revisited the physiological notion that play allows children to maintain an optimal level of arousal (Berlyne, 1969) by generating stimulation through novelty and risk (Fein, 1981). Other biologically based theories attempt to explain rough-and-tumble play as a socially acceptable outlet for aggressive impulses, especially for boys (Reynolds, 1981), and view dramatic play as a mechanism for introduction to intimate social interactions such as friendship, mating, and parenting (Pagan, 1995). These theories focus on the role of pretend play in facilitating real skills that will be necessary for successful interactions later in life and derive in part from an extensive research base on the play of young animals across species.

Interactive theories explain childhood play as healthy activity that reflects the flexibil...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- TO OUR READERS AND THEIR INSTRUCTORS: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE SERIES

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER 1: PLAYING TO LEARN—LEARNING TO PLAY

- CHAPTER 2: TEACHING AND LEARNING

- CHAPTER 3: GUIDING CHILDREN’S BEHAVIOR

- CHAPTER 4: ENVIRONMENTS FOR LEARNING

- CHAPTER 5: WORKING WITH OTHER ADULTS: PARTNERSHIPS AND COLLABORATIONS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Teaching Young Children by Kristine Slentz,Suzanne L. Krogh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Early Childhood Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.