- 273 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Ebola: Clinical Patterns, Public Health Concerns is a concise description and discussion of the Ebola virus and disease. The intended audience is medical practitioners, including those working in endemic areas as well as health-facility planners and public health practitioners. The book fills an important gap between large texts covering not only Ebola but other hemorrhagic fever viruses and brief pamphlet-style publications on the public health aspects of the infection. In light of the recent large outbreak in West Africa, this book is a part of the developing foundation needed to deal with emerging diseases.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ebola by Joseph R. Masci,Elizabeth Bass in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Epidemiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

The History of Ebola

The 2014–2016 Epidemic and Earlier Outbreaks | 1 |

The pattern of Ebola virus disease (EVD) before the 2014–2016 epidemic in West Africa was of sporadic outbreaks in rural areas of East and Central Africa (Feldmann and Geisbert 2011) involving a few dozen to a few hundred cases.

Five species of the Ebola virus have been recognized:

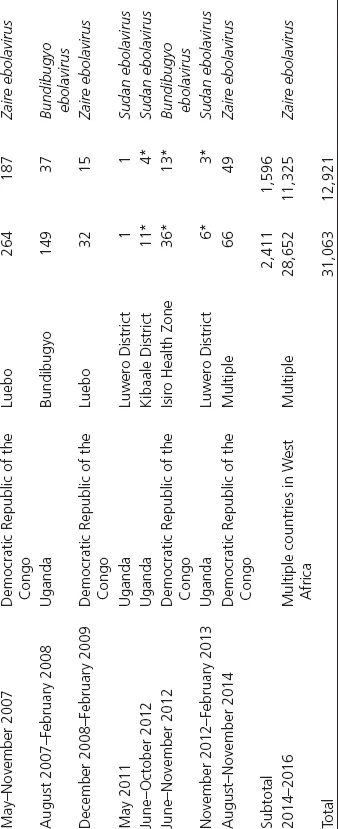

• The Zaire species, which was responsible for the West African outbreak of 2014–2016, was first recognized in 1976 and caused most of the past outbreaks of Ebola (Khan 1999).

• The Sudan species caused four epidemics in Sudan and Uganda (Onyango et al. 2007; Sanchez et al. 2004).

• The Bundibugyo species, first recognized in Uganda in 2007, caused a limited outbreak with a relatively low case-fatality rate (MacNeil et al. 2010; Clark et al. 2015).

• The Ivory Coast species has been recognized to cause disease in only one person, who appeared to acquire the infection after performing a necropsy on a chimpanzee found in an area of primate die-off (Formenty et al. 1999).

• The Reston species has only been identified in monkeys and pigs in the Philippines. Human infection has been documented by the identification of IgG antibody to the virus in a small number of individuals with only mild or asymptomatic infection (Miranda et al. 1999). Unlike other strains of the virus, the Reston virus has not been encountered in Africa. From 1989 through 1996, seven small outbreaks of this strain have been recognized in animals (CDC 2016a). These are not included in the data listed in Table 1.1 or shown in Map 1.1.

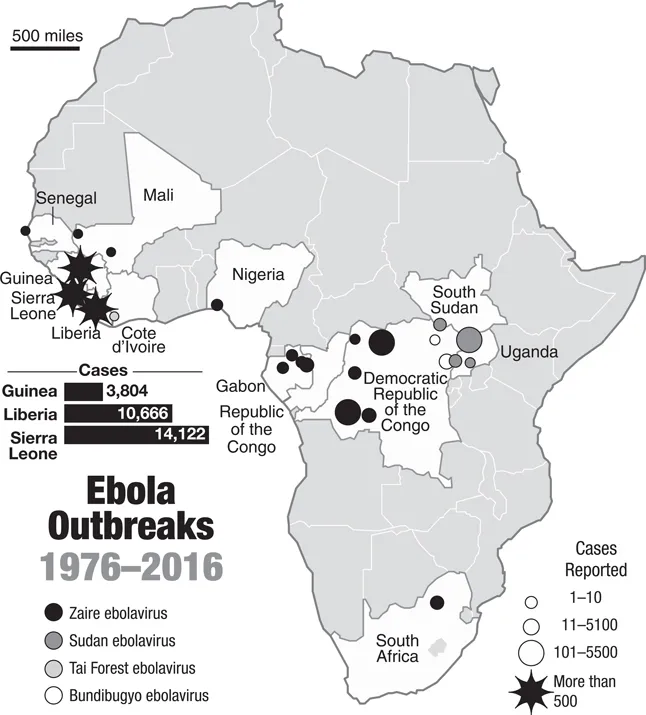

The source of Ebola outbreaks typically was not established, and transmission often involved health care facilities and workers. The first recognized outbreak of Ebola virus disease (EVD) occurred in Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo, DRC) in 1976 (Johnson et al. 1977) and was among the most significant of the Ebola outbreaks until 2014, with more than 300 cases and an observed mortality of 88%. Although the exact origin of the outbreak is not clear, transmission occurred primarily by means of contaminated needles used by health care workers (Ealy and Dehlinger 2016) at a specific hospital. The virus was named after the outbreak that occurred in the area of the Ebola River. Over the next 38 years, 21 outbreaks were recognized; most caused by either the Ebola–Zaire (ZEBOV) or the Ebola–Sudan (SEBOV) strains of the virus (Johnson et al. 1977; WHO 1978a, 1978b; Baron et al. 1983; CDC 2001). All occurred in East Africa, primarily in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Sudan, Gabon, and Uganda, and involved no more than approximately 400 cases. These were typically brought under control in relatively short periods of time, but the largest outbreak prior to 2014, which occurred in Uganda, involved more than 400 cases and lasted for one year (Ealy and Dehlinger 2016). The caseloads and death tolls from these outbreaks are shown in Graphs 1.1 and 1.2.

Despite the relatively small number of cases in these outbreaks, important insight into the epidemiology of EVD was gained. Significantly, it was recognized that close, physical contact was required for transmission and contact within health care facilities as well as burial practices were identified as particularly important factors in spread of the disease. Preliminary work on vaccines was also begun (Bukreyev et al. 2006; Martin et al. 2006; Warfield et al. 2007; Swenson et al. 2008; Geisbert et al. 2009; Tsuda et al. 2011).

Despite the understanding of the Ebola virus and EVD that was gained through investigation of these outbreaks, the West African epidemic of 2014–2016 again raised questions about the means of transmission and necessary steps for control. Its magnitude and geographical scope were both unprecedented. Graph 1.3 shows how dramatically it outstripped all previous experiences with Ebola. The fact that this outbreak occurred in a region of Africa that had not experienced EVD before, raised concerns that even more widespread disease would occur. The reason for the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa has not yet been identified, although a change in distribution of animal vectors, such as fruit bats, is likely to be a major factor. The magnitude of the outbreak, with more than 20,000 cases, is also not fully understood, although the fact that the West African cases occurred in or near large cities represented a different pattern than the earlier East African outbreaks.

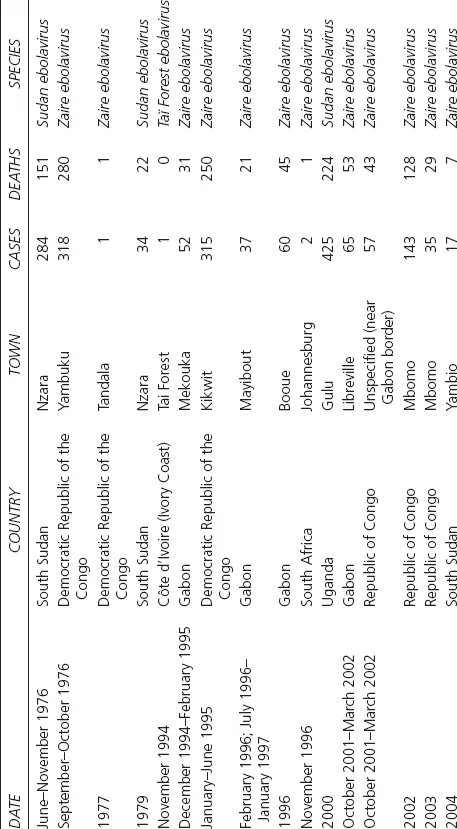

TABLE 1.1 Ebola outbreaks in Africa, 1976–2016 (accompanies Map 1.1)

Source: CDC, 2016a, https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/history/chronology.html, https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/history/distribution-map.html.

* Numbers reflect laboratory confirmed cases only.

Outside Africa, only three human cases were reported before 2014: One nonfatal case in England in 1976 attributed to a laboratory needlestick injury, and two fatal cases in Russia, one in 1996 and one in 2004, both attributed to laboratory contamination.

MAP 1.1 Outbreaks since 1976, as listed in Table 1.1. (Map by Rod Eyer.)

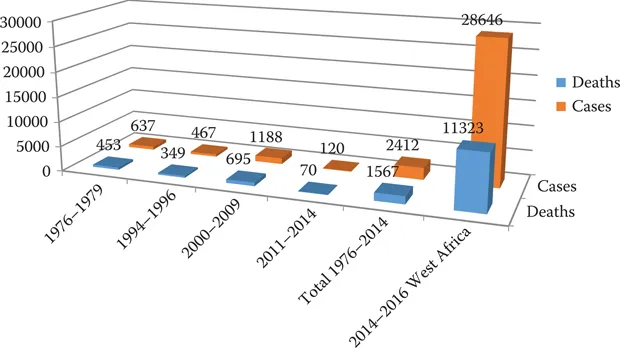

GRAPH 1.1 Ebola Cases and Deaths 1976–2014. Before the West African epidemic of 2014–2016, Ebola had been seen in a total of 24 relatively small outbreaks spread over 38 years in Central or Southern Africa, plus three laboratory cases that occurred in Russia and England.

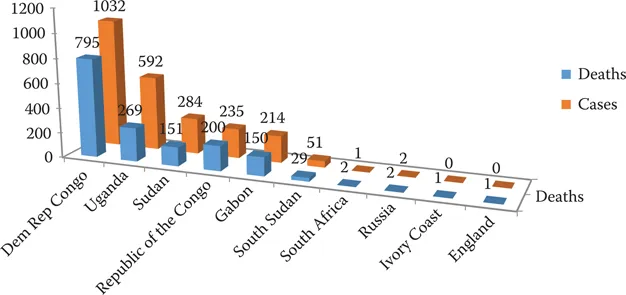

GRAPH 1.2 Ebola Cases and Deaths by Country, 1975–2014. Before the West Africa epidemic of 2014–2016, the burden of Ebola fell mostly on the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Zaire) in Central Africa and Uganda in East Africa.

GRAPH 1.3 Ebola Cases and Deaths since 1976. The West Africa epidemic of 2014–2016, which occurred primarily in three countries that had never seen a case before, dwarfed all previous outbreaks.

Although prior Ebola outbreaks had, on occasions, attracted media attention beyond Africa, the magnitude of the 2014–2016 epidemics raised unprecedented concerns all over the world. As discussed in Chapter 3, fears of spread outside West Africa led to measures that restricted travel, screened travelers from the involved countries, and consumed substantial international resources from both governmental and nongovernmental sources. The global reaction also featured high levels of fear and confusion. On a more productive note, research into vaccine development was greatly accelerated and limited data on treatment strategies were developed. On the basis of this experience, it is likely that Ebola will remain a much greater cause for concern among public health officials and governments that it ever was prior to 2014.

OUTBREAKS PRIOR TO 2014

The following information is drawn from CDC accounts (2016b) and from country-specific reports referenced below.

1976

Zaire: Zaire virus. First recognized outbreak. Occurred in Yambuku area. Transmission by close personal contact and contaminated health care needles and syringes.

Cases: 318 Deaths: 280 Mortality rate: 88%

(WHO 1978a)

Sudan: Sudan virus. Occurred in Nzara and Maridi areas. Transmission by close personal contact. Many health care workers infected.

Cases: 284 Deaths: 151 Mortality rate: 53%

(WHO 1978b)

England: Sudan virus. Needlestick injury in laboratory.

Cases: 1 Deaths: 0 Mortality rate: 0%

(Emond et al. 1977)

1977

Zaire: Zaire virus. Case identified retrospectively.

Cases: 1 Deaths: 1 Mortality rate: 100%

(Heymann et al. 1980)

1979

South Sudan: Sudan virus. Same site as the 1976 outbreak.

Cases: 34 Deaths: 22 Mortality rate: 65%

(Baron et al. 1983)

1994

Gabon: Zaire virus. Gold mining camps in the rain forest.

Cases: 52 Deaths: 31 Mortality rate: 60%

(Georges et al. 1999)

Ivory Coast: Scientist infected after performing an autopsy on a chimpanzee in the Tai Forest.

Cases: 1 Deaths: 0 Mortality rate: 0%

(LeGuenno et al. 1995)

1995

Democratic Republic of the Congo: Zaire virus. Outbreak thought to have originated from a worker who had acquired the infection in a forest near Kikwit.

Cases: 315 Deaths: 250 Mortality rate: 81%

1996

Gabon: Zaire virus. Dead chimpanzee was butchered and eaten. Cases occurred among 19 people with direct contact with the animal. The remainder were within their family members.

Cases: 37 Deaths: 21 Mortality rate: 57%

(Georges et al. 1999)

Gabon: Zaire virus. Index case occurred in a hunter possibly acquired from dead chimpanzee.

Cases: 60 Deaths: 45 Mortality rate: 74%

(Georges et al. 1999)

South Africa: Zaire virus. Medical staff member traveled to South Africa after having acquired the infection in Gabon.

Cases: 2 Deaths: 1 Mortality rate: 50%

(WHO 1996)

Russia: Zaire virus. Laboratory contamination.

Cases: 1 Deaths: 1 Mortality rate: 100%

(Borisevich et al. 2006)

2000–2001

Uganda: Sudan virus. Contact through funerals, family members, and patients without appropriate personal protective equipment.

Cases: 425 Deaths: 224 Mortality rate: 53%

(Okware et al. 2002)

2001–2002

Gabon: Zaire virus.

Cases: 65 Deaths: 53 Mortality rate: 82%

(WHO 2003)

Republic of the Congo: Zaire virus. Outbreak on the border of Gabon and the Republic of the Congo.

Cases: 57 Deaths: 43 Mortality rate: 75%

(WHO 2003)

2002–2003

Republic of the Congo: Zaire virus. Outbreak in Mbomo district.

Cases: 143 Deaths: 128 Mortality rate: 89%

(Formenty et al. 2003)

Republic of the Congo: Zaire virus. Outbreak in Mbomo district.

Cases: 35 Deaths: 29 Mortality rate: 83%

(WHO 2004)

2004

South Sudan: Sudan virus. Outbreak in Yambio county of South Sudan.

Cases: 17 Deaths: 7 Mortality rate: 41%

(WHO 2005)

Russia: Zaire virus. Laboratory contamination.

Cases: 1 Deaths: 1 Mortality rate: 100%

...Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Authors

- PART ONE The History of Ebola

- PART TWO Science and Medicine of Ebola

- PART THREE Tools for Preparing

- Appendix

- Index