![]()

| 1 | History lessons |

| Drug use trends amongst

young Britons 1980–2010 |

Introduction

Illicit and illegal drug taking by young Britons began to rise at the end of the 1980s and continued to do so until the millennium. In retrospect, we now know that the ‘children of the nineties’, of whom the Illegal Leisure cohort were a part, became the most drug-involved generation of the twentieth century. Our research spanned much of the ‘decade of dance’ and included therefore the cultural phenomenon of dance music and clubbing that emerged alongside ecstasy. It was the various publications reporting the results of the North West England Longitudinal Study – including the first edition of Illegal Leisure (Parker et al., 1998a) – that were pioneering in recording and explaining the unprecedented level of drug taking amongst these teenagers during the 1990s.

In 1998 when the first edition of Illegal Leisure was published, we did not have the luxury of good, nationally representative and annually collected data on drug use amongst young people. Prior to this time, the available evidence was patchy, or not of the same quality that we find today, making it more difficult to identify the trends in drug taking amongst young people that is our concern in the first part of this chapter.

From the late 1990s onwards, annual survey programmes that included self-reported drug taking began to appear, and two of these have become reliable trend indicators for adolescents and young adults: (1) the Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use (SDD) series of schools surveys on 11–15 year olds in England;1 and (2) the Home Office’s British Crime Survey (BCS), which picks up at age 16.2 As concerns grew about the widespread use of drugs such as cannabis, amphetamines and LSD amongst mid 1990s young people, surveys like these grew in size and detail, allowing an increasingly detailed picture to be drawn. But even these surveys are not perfect. They exclude or under-represent the young people most likely to be drug-involved (such as those in young offender institutions, excluded from school or not living in private households) and their results must be interpreted with this limitation in mind.3 Nevertheless, they allow us to chart the national trends in adolescent and young adult drug taking that have occurred since the publication of the first edition of Illegal Leisure.

The illicit drugs use ‘peak’ of the 1990s

Prior to the 1990s, government surveys on drug taking of the kind we described above were the exception rather than the rule, and most of the evidence we have from this period came from market research and media polls. Newcombe (1995), in an exhaustive review of this evidence, concluded that lifetime prevalence4 of illicit drug taking amongst young adults (typically 16–24 years) rose steadily from less than 5 per cent in the 1960s, to around 10 per cent in the 1970s, to 15–20 per cent in the 1980s. This approximate doubling each decade documents a slow but steady rise in drug taking by young people over the period. From the 1990s, however, drug taking began to rise much more dramatically. Between 1990 and 1995, the proportion of young people disclosing drug trying doubled from roughly one quarter to nearly one half of mid adolescents (Miller and Plant, 1996; Mott and Mirrlees-Black, 1995; Ramsay and Percy, 1996; Ramsay and Spiller, 1997; Roberts et al., 1997). These sharply rising rates of youthful drug taking in Britain during the early 1990s have also been documented in other developed countries (see Bauman and Phongsavan, 1999).

The second half of the 1990s began with a small but temporary drop in drug taking (Balding, 2000; Plant and Miller, 2000). The SDD surveys captured this brief downward trend in lifetime drug use rates amongst 11–15 year olds and then noted a late decade upward trend, as did the British Crime Survey, where around half of 16–24 year olds had disclosed at least some drug use in their lifetimes by the end of the decade (Ramsay et al., 2001). Overall, therefore, it appears that the 1990s were characterised by an initially steep rise that was interrupted briefly in the second half of the decade, with rates returning to their peak levels before the start of the millennium.

These historically high rates of drug trying reflected the widespread availability of many illegal substances, with increasing numbers of young people reporting having been in situations where drugs were available. Amongst those disclosing drug use, surveys during this period noted a propensity to try several substances, most often cannabis (herbal and resin) followed by amphetamines, ‘poppers’ and ecstasy, with LSD more often reported early in the decade and cocaine at its end (Ramsay and Percy, 1996; Ramsay et al., 2001). Although we recognise the limitations of the term, the youthful drug taking observed during the 1990s in the main could be characterised as predominantly ‘recreational’; that is, involving mostly weekend use of drugs in (recreational) social settings and at (recreational) leisure times. We do not suggest that ‘recreational’ use is exclusively unproblematic however (see Aldridge, 2008), and use the term throughout this book with care, to distinguish the use of the vast majority of adolescents and young adults from the daily, dependent and chaotic heroin and crack consumption usually characterised as ‘problem drug use’.

An unprecedented feature of recreational drug taking that occurred across the 1990s was the involvement of substantial proportions of groups traditionally assumed to be ‘protected’ from drug taking: girls and young women, and people from a range of higher income and professional backgrounds and aspirations. Surveys of university students, particularly medical students (e.g. Newbury-Birch et al., 2000), for example, confirm these diverse demographics.

Post 2000 drug use trends

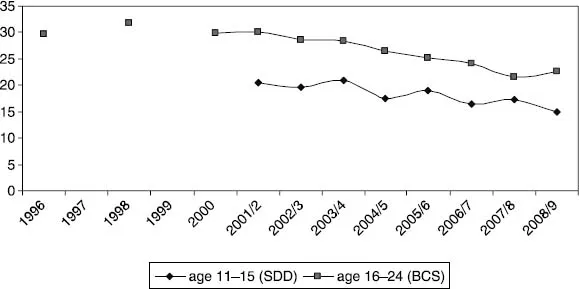

The key feature of post millennium trends in youthful drug taking is gradual overall decline. As depicted in Figure 1.1, we can see that the decrease in the prevalence of past year drug taking occurs for both younger adolescents (aged 11–15) and older adolescents and young adults (aged 16–24). In 2001, 20.4 per cent of 11–15 year olds reported the past year use of a drug, compared to 15.0 per cent in 2008. Amongst the older group, we see a more pronounced drop: from 30.0 per cent in 2001/2 to 22.6 per cent in 2008/9. Similar reductions in use also occurred for more recent use, and for frequent use in older adolescents and young adults (Hoare, 2009). It appears therefore that it is the range of using styles amongst young people that is declining: one-off trying through to regular and frequent use.

This clear downward trend in drug use amongst young people seems compelling. Have the teenagers of the 1990s ‘aged out’ of a period of excess and settled down, to be replaced by a much more moderate generation of adolescent psychoactive consumers? This is probably at least part of the story. However, these general downward trends may also obscure some important evidence that sheds a somewhat different light on the close of the ‘noughties’.

Figure 1.1 Past year prevalence (%) of ‘any drug’ use for 11–15 and 16–24 year olds: trends over time*

Sources: Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use Schools Surveys (Jotangia and Thompson, 2009); British Crime Survey (Hoare, 2009)

Note:

* The figure depicts connected data points where data are comparable. Although the SDD surveys were conducted in 1998, 1999 and 2000, the survey instrument used a different questionnaire format during these years resulting in past year prevalence figures of 11 per cent, 12 per cent and 14 per cent, respectively, suggesting a considerable lack of comparability with data collected from 2001 onwards.

The first question we might ask is this: if drug taking has been declining since the new millennium, how low did it really go? The most recent data we have for the 16–24 age group (BCS 2008/9) finds levels of drug taking not very far from their earlier millennium peak, and in reality, at almost the level surveys from the early 1990s were beginning to document.5 For example, past year use of a drug was 23 per cent6 in 1994 (Ramsay and Percy, 1996) – almost identical to the level in 2008/9 of 22.6 per cent. This similarity between levels of use in the late noughties and in the early 1990s is also apparent for younger adolescents. For example, in 2007, 33 per cent of 14 year olds indicated having ever tried a drug in the past year (Jotangia and Thompson, 2009), a figure very near to the one we found for our Illegal Leisure cohort at the age of 14 (36 per cent) in 1991. It is worth noting that when we released these early 1990s findings, the figures were regarded as unprecedented, and met with disbelief coupled with scepticism that any research that included Manchester,7 the ‘rave capital of Great Britain’ (Coffield and Goften, 1994: 5) could be representative of the rest of the country.

In other words, in spite of a near decade long decline in drug taking amongst young people, their rates of drug use remain not so very far from historically high levels. Perhaps more importantly, the levels of drug taking today sit at roughly the same as we found for our Illegal Leisure cohort in the early 1990s. In contrast to the view that today’s generation of young people is disinclined to ‘illegal leisure’, it seems they instead share much in common with adolescents of the 1990s. We will return in the concluding chapter to the question of whether the 1990s were indeed ‘special’ in relation to the advent of normalisation, or whether – taking in a much broader historical perspective across the century – the 1990s represented no more than a periodic blip in always fluctuating trends.

With the exception of Wales where rates are higher, a similar profile is found in Scotland and Northern Ireland (United Kingdom Focal Point on Drugs, 2008). Each of the UK countries still sits amongst the most drug-involved populations in the European Union and overall have the highest rates in North West Europe. For 15–16 year olds, the European Schools Survey Project, which compares substance use rates across 29 countries, continues to situate the UK in the ‘Top 5’ for lifetime prevalence particularly for cannabis and cocaine (EMCDDA, 2009).

The obvious counter to this observation is that the trend remains downward, and so long as this trajectory continues, young people’s drug taking should soon fall below levels documented amongst their early 1990s counterparts. And perhaps this will happen. However, there are some indications (albeit early ones) to suggest that drug taking may be about to plateau, possibly even increase.

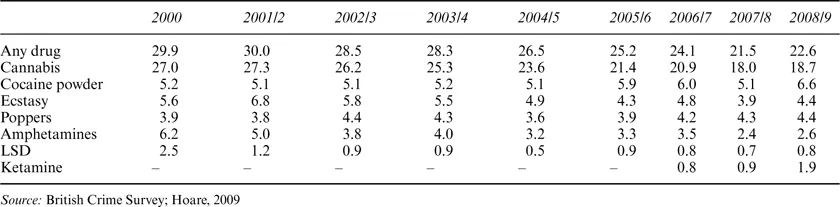

As can be observed in Figure 1.1 above, the solid downward trajectory in past year drug taking amongst 16–24 year olds has been interrupted in 2008/9, for the first time in ten years, by taking a small upward turn from 21.5 per cent to 22.6 per cent. Turning to Table 1.1 below, we can see the source of this upturn.

The increases from 2007/8 to 2008/9 in drug taking that are proportionately largest are for ketamine (from 0.1 per cent to 1.9 per cent) and cocaine powder (5.1 per cent to 6.6 per cent), as well as for any Class A drug (from 6.9 per cent to 8.1 per cent). All of these increases are statistically significant.

These small increases are not apparent across the whole of the 11–15-year-old group (Figure 1.1 and Table 1.1), but when only the oldest respondents (the 15 year olds) in this group are separated out, 8 stable or increased use for some drugs is found between 2007 and 2008. These increases occurred particularly for ketamine, the use of which doubled over the year (0.8 per cent to 1.6 per cent); with small rises for opiates (0.7 per cent to 1.3 per cent) and tranquillisers (0.6 per cent to 0.9 per cent); and stable levels of use reported for stimulants like cocaine, ecstasy and amphetamines (Jotangia and Thompson, 2009). Combined with the less pronounced rate of decline in drug taking amongst the younger adolescents over the new millennium (put another way, past year use dropped by 30 per cent amongst 16–24 year olds but only by 20 per cent amongst 11–15 year olds), these findings are indicative of the possibility that the steady decline in youthful drug taking may be coming to an end.

Amongst all young people cannabis remains dominant in drug-taking repertoires. For young adults (see Table 1.1), we find past year use of cannabis by just over one in four at the start of the decade, falling to just under one in five near its close. Similarly, for younger adolescents (see Table 1.2), past year use of cannabis fell from roughly 20 per cent in 2001 to 15 per cent in 2008. This decline in cannabis use appears to be a Europe-wide phenomenon (EMCDDA, 2009). However, there are other indications that a continued orientation toward psychoactive experimentation remains evident across the noughties.

Table 1.1 Past year prevalence (%) of drug taking amongst 16–24 year olds for ‘any drug’ and selected drugs, 2000–2008/9

Looking at the 16–24 year olds captured by the BCS surveys (Table 1.1), we can see that, whilst use of drugs aside from cannabis takes place amongst a smaller subset, we find some interesting changes over the period in the use of these stimulant and psychostimulant drugs. Firstly, use of cannabis early in the decade represented just over 90 per cent of all substance use; but by the end of the decade, this proportion had slipped to 83 per cent. This suggests that although consumption of psychoactive substances has dropped overall, a greater proportion of these consumers are selecting from a broader repertoire of drugs aside from or in addition to cannabis. This sustained orientation toward psychoactive experimentation and polydrug use amongst the minority is evident in the stability of past year use of cocaine powder over the period, which by 2008/9 actually sits at an all-time high of 6.6 per cent – the second most popular drug in the survey. In contrast, the popularity of amphetamines and LSD have both declined substantially. Perhaps most indicative of all, past year use of ketamine doubled from 2006/7/8 levels to near 2 per cent in 2008/9, and shows sustained and then rising past year use even amongst 11–15 year olds, with 1.6 per cent of 15 year olds reporting past year use in 2008 (Jotangia and Thompson, 2009).

When we started collecting data in the early 1990s, even the most enthusiastic young drug users we encountered were scathing about the taking of cocaine – its use was considered to be beyond the pale; hand-in-hand with heroin. In the first edition of Illegal Leisure, we concluded that ‘hard drugs had no place in the normalisation thesis’ (Parker et al., 1998a: 149). What this analysis shows is how quickly perceptions about drugs can change. Amongst older adolescents and young adults (including, as we shall see in coming chapters, our cohort), cocaine emerged to become the second most popular drug behind cannabis, having even overtaken ecstasy in popularity. It seems likely that the popularity of cocaine may have peaked: 2009/10 BCS figures suggest t...