![]()

Chapter 1

Managing knowledge in project environments – an introduction

Knowledge and knowledge management

We create and use knowledge to make sense of the world, to make decisions and to take action. No project would be possible without knowledge. Knowledge is the fuel that powers projects, programmes, portfolios, business as usual and all their associated processes.

To manage a single project, we need knowledge about project management: risk, quality, scheduling and so on. We need some domain knowledge to determine the solutions chosen to satisfy project requirements: at least enough to be able to communicate with the people who are building the houses or developing the software system. We also need knowledge about the context of the project: the culture of the sector in which the project is being delivered, for example – and many other factors including the organisational policies and processes used to govern the project.

No individual has all the knowledge needed to deliver a project: the knowledge is spread between team members, users and stakeholders. Knowledge from other projects is needed to make sure past mistakes aren’t repeated and existing good ideas are re-used. Knowledge from outside the project might be needed unexpectedly, for example if a risk materialises in a way no-one has anticipated.

Projects create knowledge, too: when people make sense of what needs to be done and do the work. Knowledge is embedded in project outputs – and further knowledge is created when people learn how to use them. The individual, team and organisational experience gained from doing projects is another form of knowledge: deeper understanding of what is possible, of project management and of the technical domain of the project.

All this knowledge has to be managed for project work to be successful, so it is no surprise that knowledge management (KM) is one of the most talked about topics in project management. Neither is it a surprise that everyone involved in project work is already practising KM, at least informally. Every time we seek or give advice, we are sharing knowledge. Every time we brainstorm for ideas, we are creating knowledge. Every time we produce and use good practice guides we are re-using knowledge.

KM isn’t limited to projects. It is also concerned with making sure there is a way for knowledge generated in projects to cross into business as usual; making sure knowledge is used to meet strategic organisational goals; and making sure the knowledge gained during a project is used effectively to shape and deliver projects in the future. Taking an even wider view, project KM is concerned with the global body of knowledge about project, programme and portfolio management – and how this is developed and used.

KM in project environments

KM has been around as a discipline and organisational practice since the 1990s but isn’t yet widely recognised in project environments. Specific KM activities and their associated costs and benefits are rarely included in business cases; KM doesn’t feature in most project management training; and professional associations didn’t include KM in their published guides until 2012 (APM1) and 2017 (PMI). Why? We think there are three reasons:

- 1 KM is complex. It can’t be reduced to a neat, linear process in which following pre-defined steps leads to guaranteed success.

- 2 KM is highly dependent on context. There is no one-size-fits-all way of doing it. What works in one situation can be an unmitigated disaster in another.

- 3 There is no widely accepted definition of KM.2 Different people attach different meanings to the term.3 This causes great confusion and leads to misconceptions and misunderstandings. We will see in Chapter 2 that the root of this confusion is often different perspectives on the meaning of ‘knowledge’.

In many project environments, KM is limited to end of project ‘lessons learned’ activities; based on the misconception that KM is about capturing and disseminating knowledge. ‘Lessons learned’ has become the project management term for KM and although it sometimes refers to good KM practices, all too often it means maintaining a repository of ‘lessons’ that are never used (Figure 1.1). This is not an effective way of managing knowledge!

Why does any of this matter? Because KM adds value and can contribute significantly to project, programme and portfolio success – and the project management world is missing out on it. KM experience and thinking from beyond the project management world can change this.

Project environments

The importance of project management across every industry sector has led to the formalisation of project management techniques into frameworks such as PRINCE2® and development of the project management profession by bodies such as the Project Management Institute (PMI) and the Association for Project Management (APM). Each has its own definitions for terms such as project, programme and portfolio. The practice of delivering projects remains very diverse and techniques are used with varying degrees of structure and rigour. Additionally, the terms ‘project’ and ‘project management’ have become shorthand for project, programme and portfolio management.

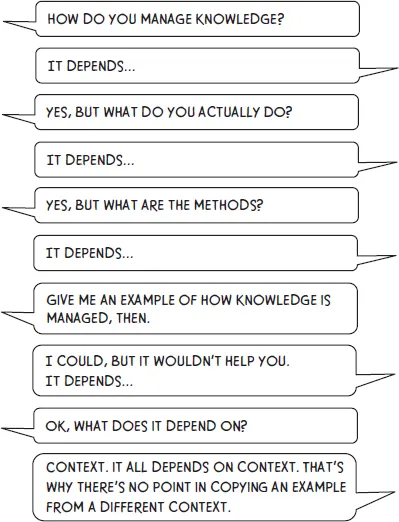

Figure 1.1 Lessons learned. A typical conversation between a project manager and a knowledge manager

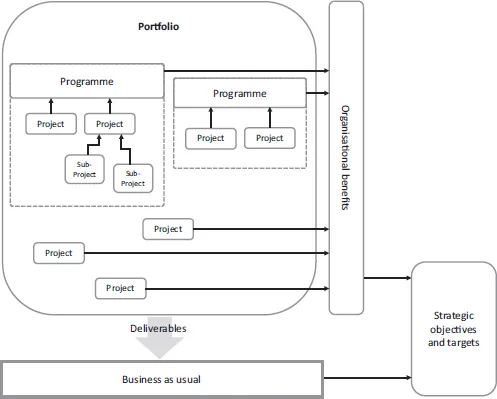

To clarify the terms we use in this book, project environment refers to any arrangement of portfolios, programmes and projects; the structures used to manage and support them; and how these elements relate to each other, to business as usual and organisational benefits. Project environment can also refer to situations where multiple organisations work together and where benefits are created for external users. Project work and project management are used as shorthand for the work done in project environments.

Figure 1.2 shows the elements of a project environment in a traditional, hierarchical relationship. In practice there are many variations in the way the elements are arranged and in the relationships between project work and users of project outputs.

Figure 1.2 The project environment

Aim of Managing Knowledge in Project Environments

The aim of this book is to help you understand how to manage knowledge effectively so that it contributes to successful project work. The book can be used to build KM into project management practices, design new KM interventions and to evaluate and improve existing KM practices.

There are plenty of ‘how to do KM’ practitioner guides out there. Some of them are very good. Most cover only one or two aspects of KM and don’t explain the importance of context. There are some excellent academic texts on managing knowledge. Most don’t actually explain how to do KM. This book aims to fill the gap between practitioner guides and academic texts by presenting theory and practice – and explaining the connections between the two in project environments.

Intended readership

Managing Knowledge in Project Environments is written for project practitioners working on projects, programmes and portfolios. This includes people who work in PMOs and people such as project sponsors who can make a difference to the way knowledge is managed.

It is also written for knowledge managers who find themselves in project environments and need a way of explaining KM to project practitioners who expect a series of processes with accompanying templates.

More than anything, Managing Knowledge in Project Environments is written for people who want to improve the management of knowledge: people who are frustrated by poor knowledge sharing; people who are learning about project management and want to understand what KM is about; and people whose experience tells them the ubiquitous ‘lessons learned’ database approach to KM in projects doesn’t always work.

The thinking behind Managing Knowledge in Project Environments

In KM, knowledge is not managed directly. It can’t be, because knowledge is intangible. KM focuses on creating a working environment that supports and motivates people to engage in the KM thinking and activities needed for the work being done.

Managing knowledge in project environments is not just a case of adding a few KM activities to projects. It involves looking at project work through a knowledge lens: understanding how knowledge contributes to the success of project work and therefore of organisations, and actively considering and managing the knowledge aspects of project work to create better organisational outcomes. KM is not separate from project management: it is part of project management and can make project work more effective.

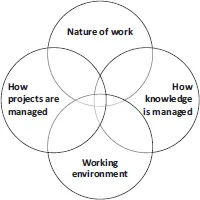

The KM context

Different kinds of project work require different working environments and different KM activities. The working environment is heavily influenced by the way projects are managed, the way knowledge is managed and, to some extent, by the KM activities themselves. We call these overlapping influences the KM context (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 The KM context

No one-size-fits-all

It follows that there is no one-size-fits-all way of doing KM and that copying what someone else is doing is unlikely to be successful. This is not to devalue learning and experience, both of which are important. It just means that what works in one context won’t necessarily work in another (Figure 1.4).

KM success

KM is not done for its own sake: it is done to further organisational and project goals, solve problems and improve performance. Like projects, KM is successful when it has a positive impact on goals, problems and performance.

Figure 1.4 How do you manage knowledge? A typical conversation between a project manager and a knowledge manager

KM context factors and clusters

We define the KM context using a set of factors – things that make a difference to the success of KM. The factors are grouped into the four clusters shown in Figure 1.3: the nature of the work being done; the working environment; the way projects are managed and the way knowledge is managed. Each cluster influences, and is influenced by, the other three. The common thread running between the clusters is people. Decisions made in all four clusters affect the motivation and ability of people to work effectively.

For KM to contribute to the success of project work, the clusters need to be aligned so that they work together in harmony. At a more detailed level, individual factors need to be aligned. Aligning the clusters and factors is the basis of a KM strategy: what you plan to do so that KM helps you meet your project, programme and therefore organisational objectives. Each cluster and each factor is also important in its own right.

Because the context factors are the things that make a difference, they are the focus for building KM into project management practices. They can also be used to analyse and improve the effectiveness of existing KM practices. The context factors are explained further in Chapter 3.

KM scope, KM actors and judgement

KM can ...