Ports and Networks

Strategies, Operations and Perspectives

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Ports and Networks

Strategies, Operations and Perspectives

About this book

Written by leading experts in the field, this book offers an introduction to recent developments in port and hinterland strategies, operations and related specializations. The book begins with a broad overview of port definitions, concepts and the role of ports in global supply chains, and an examination of strategic topics such as port management, governance, performance, hinterlands and the port-city relationship. The second part of the book examines operational aspects of maritime, port and land networks. A range of topics are explored, such as liner networks, finance and business models, port-industrial clusters, container terminals, intermodality/synchromodality, handling and warehousing. The final section of the book provides insights into key issues of port development and management, from security, sustainability, innovation strategies, transition management and labour issues.

Drawing on a variety of global case studies, theoretical insights are supplemented with real world and best practice examples, this book will be of interest to advanced undergraduates, postgraduates, scholars and professionals interested in maritime studies, transport studies, economics and geography.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part 1

Ports and networks

1

Port Definition, Concepts and the Role of Ports in Supply Chains

1.1 Introduction

1.2 The primary function of a port and its main actors

- Bulk cargo can be defined as cargo that is transported unpackaged in large quantities. Often a distinction is made between dry and liquid bulk cargo. The main dry bulk cargoes are coal, iron ore and grain.

- Liquid bulk products are usually split up in two groups: crude oil and refined oil products. Of course, the latter category consists of a variety of products, such as naphtha, gasoline, diesel fuel, kerosene and liquefied petroleum gas.

- General cargo, sometimes also referred to as ‘break bulk’, includes steel, nonferrous metals; and paper, wood and fruit if transported on pallets and in rolls, bales, sacks, ‘big bags’, packages and bundles. In contrast with dry and liquid bulk, general cargo can be counted apiece if the goods are loaded and unloaded.

- Container cargo is cargo stored in standardised boxes, generally 20 or 40 feet in length. Containers are units that are used for a large variety of goods, such as electronics, textiles, chemicals and machinery. Because of the standardised measures, containers can be handled in the same way in container ports and in port-related transport, resulting in low transport costs.

- Roll-on/roll-off cargo is ‘wheeled cargo’. It encompasses all transport flows where vehicles like cars, trucks, semi-trailer trucks and trailers drive on and off the ship.

- A final commodity group is project cargo, consisting of all kinds of special cargoes that need to be transported overseas and require a special transport

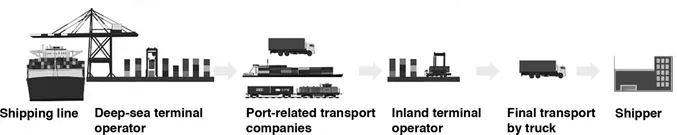

- Deep-sea terminal operator (also called stevedore or terminal operating company). The main activity of a deep-sea terminal operator is loading and unloading ships and the temporary storage of the goods. A deep-sea terminal operator focuses mainly on the handling of one cargo type, because the technologies with regard to handling and storage of the different commodities vary. In general, deep-sea terminal operators have two different customers: shipping lines and the importing or exporting companies (shippers). In some transport chains, where cheap and reliable access to port services is important, shippers choose to vertically integrate. In this case, they have their own terminal operating company, or they have a majority share in a terminal. Some terminal operators exploit terminals in different ports all over the world, while others are only active in one port.

- Shipping line. The core business of shipping lines is to operate ships and provide shipping services. In maritime transport, a distinction can be made between liner shipping and tramp shipping. Liner shipping offers transport with a fixed route and fixed schedule. This can be compared with a bus line service on a route with a fixed timetable and stops. Shipping lines in tramp shipping do not have a fixed route. Ships sail from one port to another depending on the demand for cargo. Liner shipping is offered for containers, cars and RoRo-cargo (roll-on/roll-off–cargo), while tramp shipping is used for commodities such as oil and iron ore. Shipping companies do not necessarily own ships. In many cases, specialised ship-finance and ship-owning companies play a role and charter ships for a relatively long period to the shipping companies. The main business of shipp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of boxes

- List of formulae

- List of contributors

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- PART 1 Ports and networks: strategies

- PART 2 Ports and networks: operations

- PART 3 Ports and networks: perspectives

- Index