![]()

Part I

Fundamentals of Music and Audio

![]()

Part IA

Fundamentals of Music

![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Pitch

Even the most complex subjects can be reduced to a series of far less intricate components. In learning to read and write in English, you first learned the letters of the alphabet, how these letters combine to form words, how words combine to form sentences, how sentences combine to form paragraphs, and how paragraphs combine to form compositions. The same process applies to the study of music. In this chapter, you will concentrate on the smallest elements of the Western musical language, and these elements will be combined in later chapters to form more elaborate structures.

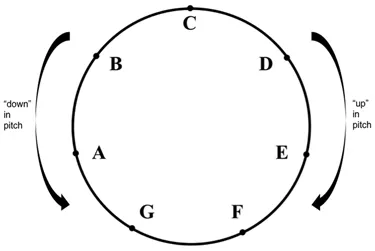

Music is often described as being composed of four major elements: melody, harmony, rhythm, and form. In order to discuss melody and harmony, you first need to understand the primary element of pitch. A pitch is a musical sound occurring at a point along the continuum of audible frequencies from low to high. Pitches are traditionally named using the seven letters A through G, which combine to form the musical alphabet. It may be helpful to view the musical alphabet—an infinitely repeating series of seven letters—on a clock face diagram, as shown in Figure 1.1. Counting “up” in pitch involves moving clockwise through the diagram, such as the move from C to D, or from G to A, or, notably, from B up to C. Conversely, counting “down” in pitch is associated with counterclockwise moves.

Fig. 1.1 Clock face diagram of the musical alphabet

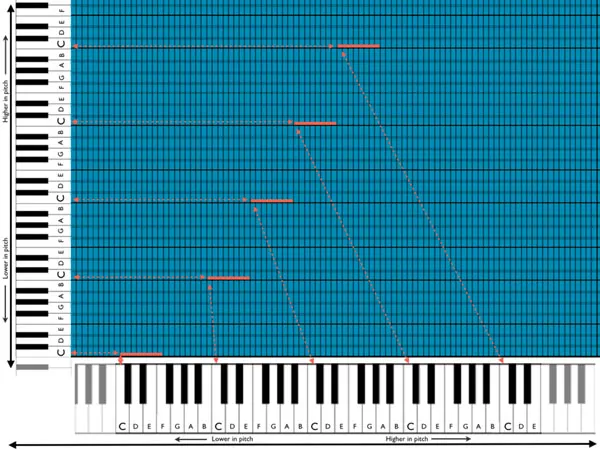

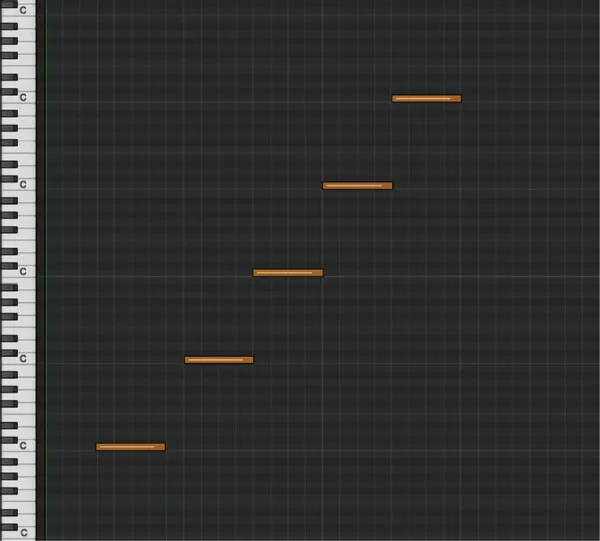

The Keyboard and the Piano Roll Editor

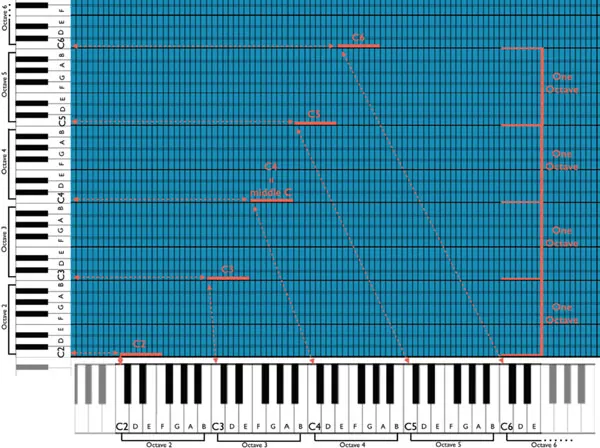

Though Figure 1.1 can be helpful in understanding pitch relationships abstractly, this book more frequently uses a diagram of the piano keyboard. This is because the keyboard provides us with the clearest visual representation of pitch organization of any instrument. It is also a very common instrument in a variety of musical contexts. Indeed, basic keyboard skills are essential for any serious musician today, regardless of one’s primary instrument, and they are assumed in most professional situations. Moreover, the keyboard is the primary tool used for entering MIDI information in sequencing projects and is directly related to the main method of displaying pitch in today’s digital audio workstations—the piano roll editor, which was first discussed in the Introduction (see Figures 1.2a and b). Note that pitches sound lower on the keyboard as you move to the left, while they sound higher as you move to the right. As you may recall, this left/right relationship is simply rotated 90 degrees in the formation of the piano roll editor, allowing you to view pitches in a down/up manner that more directly relates to the auditory experience and staff notation.

Fig. 1.2a Pitch relationships between the keyboard and the piano roll editor

Fig. 1.2b Piano roll editor in Apple’s Logic Pro X software

Pitch and Pitch Class

The pitches represented in Figures 1.2a and 1.2b share the same letter name, C, and sound quite similar to one another. This is because they are members of the same pitch class—a group of pitches possessing the same letter name and similar sounds that are separated by octaves. An octave is the interval—or distance—from one pitch of a given letter name to another with the same letter name that is heard in a different pitch region, or register. Octaves are seven positions away from one another in the musical alphabet, for a total covered distance of eight positions—hence the term “oct-ave.”

Pitch class members that are separated by one or more octaves do not sound exactly the same, as they possess differences in both tone “height” and tone color, or timbre. However, they do sound similar, and can be considered roughly equivalent in many musical contexts. This principle is known as octave equivalence. Pitches sharing the exact same sound and letter name are called unisons.

In many cases, it is necessary to be able to discuss a given pitch very precisely, taking into account its specific register. To accomplish this, it is common to label pitches with numbers relating to the octave in which they reside. These numbers, or octave designations, follow the labeling system created by the Acoustical Society of America (see Figure 1.3). Notice how each member of pitch class C begins a new octave, with middle C, the pitch performed nearest the center of the 88-key keyboard, labeled as C4. It is important to note that octave designations are not internationally standardized, and indeed, some music production software and hardware labels middle C as C3 instead of C4. This book, however, will consistently follow the Acoustical Society of America standard.

Fig. 1.3 Pitch relationships between the keyboard and the piano roll editor with octave designations

Half Steps and Whole Steps

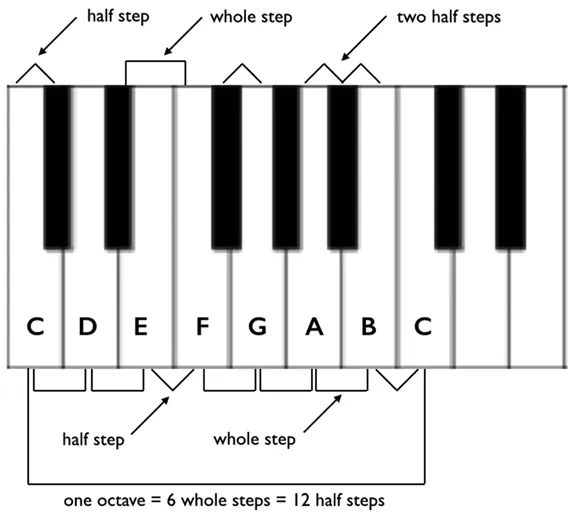

All of the adjacent pitches in Figure 1.3 are members of the same pitch class, C, and are separated by exactly one octave, which is a relatively large interval. It is also necessary to discuss smaller intervals between members of different pitch classes. The smallest distance between two different pitches is called a half step or semitone, which is the interval between adjacent keys on the keyboard. For example, the distance from a black key to a white key on either side is always a half step interval. There are also half steps between some white keys—B and C as well as E and F. Each octave interval is made up of 12 half steps.

A whole step or tone is an interval that is twice the size of a half step. In other words, two half steps equal one whole step. This is the second smallest distance found on the keyboard. A whole step above A is B because it spans two half steps and skips a key on the keyboard. A whole step below F is performed on the black key directly to the left of E, as E would be only a half step below F. Each octave interval is made up of six whole steps (see Figure 1.4).

Fig. 1.4 Half and whole steps on the keyboard

Accidentals

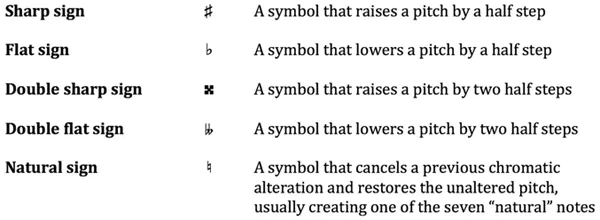

Thus far, you have learned the seven letters of the musical alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. These letters are associated with pitches performed on the white keys on the keyboard. In order to refer to the pitches that are played using the black keys on the keyboard, accidentals are used. An accidental is a symbol used to alter the pitch of a note in a given direction without changing its letter, creating a chromatic alteration. The most common accidentals are sharp signs and flat signs. A sharp sign raises a note by a half step, while a flat sign lowers a note by a half step. Another common accidental is the natural sign, which typically directs the performer to one of the “natural” notes (A, B, C, D, E, F, or G) and has a “canceling effect” in music notation that is discussed in further detail later in this chapter. Less common accidentals include the double sharp sign, which raises a note by two half steps (or a whole step), and the double flat sign, which lowers a note by two half steps (or a whole step). A summary of accidentals is provided in Figure 1.5.

Fig. 1.5 A summary of accidentals and their effects

Enharmonic Equivalents

Although the majority of the notes that include sharp signs and flat signs are performed on the black keys, a few are actually played on the white keys, in the same positions as “natural notes.” Examples include EB, BB, Cb, and Fb, which are performed using the same keys as F, C, B, and E respectively (see Figure 1.6). Additionally, most notes that include double flat signs and double sharp signs are played on the white keys. Indeed, every note can actually be named in a few different ways. For example, a GB and an Ab within the same octave will produce the same pitch and use the same key on the keyboard. Notes like these, which sound the same but are named differently, are called e...