- 110 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

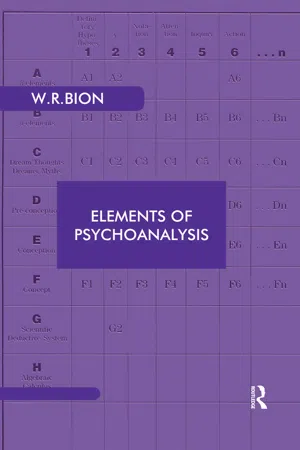

Elements of Psychoanalysis

About this book

Elements is a discussion of categorising the ideational context and emotional experience that may occur in a psychoanalytic interview. The text aims to expand the reader's understanding of cognition and its clinical ramifications.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Elements of Psychoanalysis by Wilfred R. Bion in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

BECAUSE PSYCHO-ANALYTIC theories are a compound of observed material and abstraction from it, they have been criticized as unscientific. They are at once too theoretical, that is to say too much a representation of an observation, to be acceptable as an observation and too concrete to have the flexibility that allows an abstraction to be matched with a realization. Consequently a theory, which could be seen to be widely applicable if it were stated abstractly enough, is liable to be condemned because its very concreteness makes it difficult to recognize a realization that it might represent. Conversely, if such a realization is available, the application of the theory to it may seem to involve a distortion of the meaning of the theory.1 The defect therefore is twofold: on the one hand description of empirical data is unsatisfactory as it is manifestly what is described in conversational English as a “theory” about what took place rather than a factual account of it2 and on the other the theory of what took place cannot satisfy the criteria applied to a theory as that term is employed to describe the systems used in rigorous scientific investigation.3 The first requirement then is to formulate an abstraction,4 to represent the realization that existing theories purport to describe. I propose to seek a mode of abstraction that ensures that the theoretical statement retains the minimum of particularization. The loss of comprehensibility that this entails can be made up for by the use of models to supplement the theoretical systems. The defect of the existing psycho-analytic theory is not unlike that of the ideogram as compared with a word formed alphabetically; the ideogram represents one word only but relatively few letters are required for the formation of many thousands of words. Similarly the elements I seek are to be such that relatively few are required to express, by changes in combination, nearly all the theories essential to the working psycho-analyst.1

Most analysts have had the experience of feeling that the description given of characteristics of one particular clinical entity might very well fit with the description of some quite different clinical entity. Yet that same description is rarely an adequate representation even of those realizations to which it seems fairly obviously to be intended to correspond. The combination in which certain elements are held2 is essential to the meaning3 to be conveyed by those elements. A mechanism supposed to be typical of melancholia can only be typical of melancholia because it is held in a particular combination. The task is to abstract4 such elements by releasing them from the combination in which they are held and from the particularity that adheres to them from the realization which they were originally designed to represent.

For the purpose for which I want them the elements of psycho-analysis must have the following characteristics: I. They must be capable of representing a realization that they were originally used to describe. 2. They must be capable of articulation with other similar elements. 3. When so articulated they should form a scientific deductive system capable of representing a realization suppose one existed: other criteria for a psycho-analytic element may be educed later.

I shall represent the first element by ♀ ♂; as I have discussed it at length in Learning from Experience1 my account here will be brief. It represents an element that may be called, though with a loss of accuracy, the essential feature of Melanie Klein’s conception of projective identification. It represents an element such that, if it were less it could no longer be related to projective identification at all; if it were more it would carry too great a penumbra of associations for my purpose. It is a representation of an element that could be called a dynamic relationship between container and contained.

The second element I represent PS ↔ D. It may be considered as representing approximately (a) the reaction between what Melanie Klein described as the paranoid-schizoid and depressive positions, and (b) the reaction precipitated by what Poincaré2 described as the discovery of the selected fact.

I have already discussed the signs L, H and K, in Learning from Experience. They represent links between psycho-analytic objects. Any objects so linked are to be assumed to be affected by each other. The realizations from which they have been abstracted are usually represented by the terms “love,” “hate,” and “know.”

Using the notation R derived from the word “reason” and the realizations it is thought to represent, and I derived from the word “idea” and all realizations it represents including those represented by “thought”; I is to represent psycho-analytical objects composed of α-elements, the products of α-function. I have described what I mean by this term elsewhere (Learning from Experience). By α-function I mean that function by which sense impressions are transformed into elements capable of storage for use in dream and other thoughts. R is to represent a function that is intended to serve the passions, whatever they may be, by leading to their dominance in the world of reality. By passions I mean all that is comprised in L, H, K. R is as associated with I in so far as I is used to bridge the gap between an impulse and its fulfilment.1 R2 insures that it is bridged to some purpose other than the modification of frustration during the temporal pause.

Notes

1 An instance of this can be seen in J. O. Wisdom’s paper on “An examination of the Psycho-analytical Theories of Melancholia”, p. 18, where he clearly states the need for an extension of theory, but sees that it involves making a supposition about what M. Klein’s view could have been.

2 In grid terms, too much G3 instead of D or E3.

3 Too much C3 instead of G4.

4 The concept of abstraction will be discussed at length; its use in the early stages is provisional. Such a formulation would be in G.3.

1 Compared with the tendency to produce ad hoc theories to meet a situation when an existing theory, stated with sufficient generality, would have done. Compare Proclus, quoted by Sir T. L. Heath, on Euclid’s Elements (Heath, T. L.: The Thirteen Books of Euclid’s Elements, Chap. 9, C.U.P. 1956).

2 A consequence of Ps ↔ D. See Chap. 18.

3 A consequence of ♀♂. See Chap. 18.

4 See footnote 4 on p. 1.

1 Bion, W. R.: Learning from Experience. Heinemann.

2 Poincaré, H.: Scientific Method. Dover Press.

1 Freud, S.: Two Principles of Mental Functioning.

2 I have not carried through the discussion of R because I do not yet feel in a position to see its implications. I include it because my clinical experience persuades me of the value of such an element and others may be able to use it incompletely worked out though it is. See Hume: A Treatise of Human Nature, Book II, Part III, Section 3. Clarendon Press 1896.

Chapter Two

PSYCHO-ANALYTIC theories suffer from the defect that, in so far as they are clearly stated and comprehensible, their comprehensibility depends on the fact that the elements of which they are composed become invested with fixed value, as constants, through their association with the other elements in the theory. This phenomenon is analogous to the phenomenon of alphabetic script where meaningless letters can be combined to form a meaningful word. The elements in Freud’s theory of the Oedipus situation, for example, are combined, by their association to form the narrative of the Oedipus myth, and so achieve a contextual meaning that gives them a constant value. As elements in a description of a realization that has been already discovered this is essential to their usefulness: as components of a theory that is to be used in the illumination of realizations yet to be discovered it is a defect because the constant value impairs the flexibility needed.

The abstractions intended to be elements of psychoanalysis should be capable of combination to represent all psycho-analytical situations and all psycho-analytical theories. For this to be true the chosen elements must be essential in the sense described on p. 7. I propose to devote discussion to this topic before pursuing the problem of abstraction1 of which the solution is so important if the elements chosen, as the elements of psycho-analysis, are to be capable of use in the construction of theoretical systems. The first step is to consider what phenomena of those present in analytical practice appertain to the elements of psychoanalysis. We may proceed by following three courses:

- We may search for the elements as their secondary1 qualities occur and may be recognized in psychoanalytical experience.

- We may search for the elements as their representations occur and can be isolated in psychoanalytic theory.

- We may investigate procedures 1 and 2, and combine them as a source from which to abstract elements.

I shall consider first the observability of the chosen elements, although it might be thought, since the elements enter into the composition of all psychoanalytic theories and are essential, that the first need would be to see if these elements can be detected in the theories.

If a patient says he cannot take something in, or the analyst feels he cannot take something in, he implies a container and something to put in it. The statement that something cannot be taken in must not therefore be dismissed as a mere way of speaking. It implies, furthermore, a sense of at least two objects. It might be stated ♀♂ ≥ 2. In certain circumstances, also observable in analysis, the sense of “two-or-moreness,” may become obtrusive. For the present I shall ignore the implication of number although the element I wish to isolate cannot be correctly described unless it is understood that ♀♂ ≥ 2.

It is obvious that the number of occasions on which it is verbally stated that something is “in” something also might be innumerable and correspondingly insignificant. The patient is “in” analysis, or “in” a family or “in” the consulting room; or he may say he has a pain “in” his leg.1 Judgement of the importance or significance of the emotional event during which such verbalizations appear to be apposite to the emotional experience depends on the recognition that container and contained, ♀♂, is one of the elements of psycho-analysis. We may then judge whether the element ♀♂ is central or merely present as a component of a system of elements that impart meaning to each other by their conjunction.

Considering now whether it is necessary to abstract the idea of container and contained as an element of psycho-analysis I am met with a doubt. Container and contained implies a static condition and this implication is one that must be foreign to our elements; there must be more of the character imparted by the words “to contain or to be contained.” “Container and contained” has a meaning suggesting the latent influence of another element in a system of elements. As the same objection can be levelled against “to contain or to be contained” I shall assume that both statements are contaminated by the presence of elements of an undeclared system of elements (e.g. the latent effect of the model discussed by me in Learning from Experience). I shall therefore close the discussion by assuming there is a central abstraction unknown because unknowable yet revealed in an impure form in statements such as “container or contained” and that it is to the central abstraction alone that the term “psycho-analytical element” can be properly applied or the sign ♀♂ allocated. From this definition it is clear that the supposed ps...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- CHAPTER ONE

- CHAPTER TWO

- CHAPTER THREE

- CHAPTER FOUR

- CHAPTER FIVE

- CHAPTER SIX

- CHAPTER SEVEN

- CHAPTER EIGHT

- CHAPTER NINE

- CHAPTER TEN

- CHAPTER ELEVEN

- CHAPTER TWELVE

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN

- CHAPTER FOURTEEN

- CHAPTER FIFTEEN

- CHAPTER SIXTEEN

- CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

- CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

- CHAPTER NINTEEN

- CHAPTER TWNTY

- INDEX