![]()

Public health and the future of life on the planet

Valerie A. Brown, Jan Ritchie, John Grootjans, and Bernard G. Rohan

Summary

The task of public health has always been to interpret and respond to the effects on human health of major social and environmental change. This has been true throughout the development of urbanism, industrialisation, globalisation and now planetary environmental change. With global life-support systems at risk, the role of public health has broadened yet again—this time to addressing the integrity of ecological systems so these continue to support the variety of life on Earth. For perhaps the first time it is imperative that the public health practitioner acts as if the sustainability of the environment were of equal importance with the sustainability of our species. In this chapter the work of the 21st century public health practitioner is placed in the context of the global social, economic and ecological changes of our time. We propose an integrative decision-making framework for the public health practitioner or student to use to critically examine the current conditions of global ecological integrity that are affecting the wellbeing of humankind. The framework incorporates an open learning process as the task requires an open, inclusive and innovative perspective—and humility in not assuming that we know all the answers.

Chapter 1 Living

Public health and the future of life on the planet

Valerie A. Brown, Jan Ritchie, John Grootjans and Bernard G. Rohan

Key words

Diversity, equity, globalisation, humility, inclusivity, integrity, learning, localisation, potential, precaution, sustainability, sustainable development

Learning outcomes

Public health practitioners and students will be able to:

• critically evaluate the principles and practices offered for ensuring ecological sustainability as a precondition for safeguarding the future of life on the planet;

• interpret current knowledge and understanding of sustainability principles and practice in the decision-making context and biosocial circumstances in which they operate; and

• use a community learning model of public health practice that will enable them to advance their own and their clients’ understanding of the importance of sustainability for health.

Outline

1.1 Health and sustainability: a new direction for public health

1.2 Defining sustainable development: moving to sustainability

1.3 New ideas for new public health: overview of recommended readings

1.4 Integrative decision-making about place-based issues (D4P4): an open learning framework

1.5 Sustainability as public health practice: criteria for future-oriented practitioners

Learning activities

1.1 Value line: clarifying ideas of sustainability and health

1.2 Reality check: what holds this planet together?

1.3 Decision-making frameworks: how do we put knowledge into action?

1.4 Practitioner as change agent: continuum of change

Reading

AtKisson, A. 1999, Believing Cassandra: An optimist looks at a pessimists world, Scribe Publications Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Chapter 1

McMichael, A.J. 2001, Human Frontiers, Environments and Disease: Past patterns, uncertain futures, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Chapter 1

Soskolne, C.L. and Bertollini, R. 1999, Global Ecological Integrity and ‘Sustainable Development’: Cornerstones of Public Health, WHO European Centre for Environment and Health, Rome, http://www.euro.who.int/document/gch/ecorep5.pdf [22 January 2004]

1.1 Health and sustainability: a new direction for public health

At one of the project management team meetings to discuss the development of this book, a profound question was put to the group: why sustainability? In other words, for what reason were we working so hard? The answer is not as simple as you might imagine. The people at the meeting did not say things such as, ‘because our planet is warming’, ‘our resources are running out’, or ‘our environments are becoming toxic waste dumps’. Those answers were too simplistic and, as time has shown, there are no simple solutions. After a great deal of discussion, one of the group simply said, ‘When in 20 years’ time one of my grandchildren asks me why our generation let things go on for so long when everything was telling them time was running out, I want to be able to tell them I did all I could.’

Why sustainability?

As Capra (1983) suggested in The Turning Point, we are at a point in history where the essential nature of our relationship to the environment is changing. Like Capra, we believe the next generation will not understand the motivations for our purely growth-driven actions today, just as we found it hard to understand the mid-20th century motivation for tolerating the spread of fascism. We would like readers to begin this book by contemplating answers for the children of 2020.

Baum’s The New Public Health (2002) puts the argument for a new approach to public health based on the increase in globalisation and decrease in equity in and between populations. This book takes this new direction one step further and argues that if public health is to consider its full responsibility to the health of the public, it has no choice but to give major consideration to global sustainability.

Survey results are indicating most people believe the environment is an important consideration and that the community has good knowledge of environmental issues (Mainieri et al. 1997). If this is so, why is there no corresponding increase in action for the environment, even in simple issues such as waste recycling? This conundrum is also true of the response of public health practice in general: while there is an obvious connection between health and a state of global ecological integrity, there seem to be only isolated reactions on behalf of public health practitioners toward global ecological integrity.

Public health has always been regarded as a response to changes in the biophysical landscape.

Such a reorientation of public health is nothing new. Public health has always been regarded as a response to changes in the biophysical landscape. Hippocrates of Kos and his school supported the idea that nature—which included the human body—could cure itself, and that the quality of the environment had an important bearing on this process. The beginning of public health as a formal practice was a courageous response by Snow (Ashton and Seymour 1988) to prevent water being pumped from a cholera-infected supply and was carried out in the face of extensive disapproval from the local community. His removing the pump handle, acting on indicative but not final evidence (that is, applying the precautionary principle) halted the epidemic … but raised the fury of the water-deprived population. These characteristics—acting for the public good when there is a risk too great not to act on, even if the evidence is not all in and before the public is aware of the risks—are still part of public health practice today.

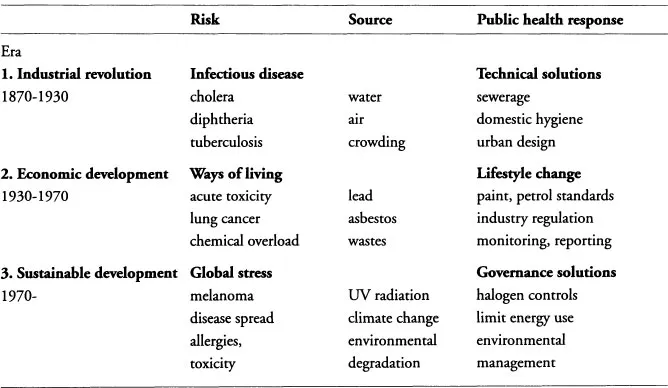

We are now in the third of three phases in public health practice arising from health risks of the industrial revolution, economic development and the current concern about sustainable development (Figure 1.1). Each era has called on different responses from public health practitioners and their colleagues (Brown et al. 1992). In the first phase reducing the risks of infectious disease epidemics lay in the hands of the civic authorities, who made decisions about urban renewal, sewerage and hygiene. Legal action saw the emergence of restraints on public freedom of some to safeguard the health of all, including quarantine, condemned housing and controls on contamination of water sources and waterways.

After major epidemics of infectious diseases had been controlled (at least in developed countries) by changes in public infrastructure, the second phase of public health emerged with the industrial byproducts and wastes of economic development. Technical testing capacities for monitoring air, water and soils became major professional skills of public health practitioners. As the pressures of industrialisation increased, the global changes identified in Figure 1.1 not only arose but also made an increasing and more immediate impact at the local scale.

Figure 1.1 Three eras of public health practice

Source: Adapted from Brown et al. 1992

By the last quarter of the 20th century, public health practice was faced with an even greater change in its application. As well as increases in its existing responsibilities there came the added responsibility of protecting local environmental life-support systems. Moreover, this responsibility is also for the future; not only for the local population but also for that population as a unit of the planetary environment. Long-term protection has always been the concern of public health, but single localities can no longer be protected in isolation from their neighbours. The long shadows of the major cities, the rapid transport of goods and services mean that collaborative regional and national action is required. Local issues still offer the unit of action when dealing with global concerns, leading practitioners to seek to widen their links with a range of professions, expert advisors and community interests at other scales of action. Contamination of city air by transport exhausts, blue-green algae affecting many waterways and the leaching of nitrates into groundwater from crop runoff are examples of unsolved health risks arising from environmental disruption. Maintaining sustainable ecosystems as essential prerequisites for human health is now beginning to be accepted as part of the responsibility of public health. This newly emerging knowledge base for public health utilises knowledge from all three phases in Figure 1.1. This book is designed to stimulate a new generation of public health workers to recognise the connections between the health of the ecosystem and the health of populations. It is the first phase of a continuing dialogue about how public health practitioners can participate in action for sustainability as an essential consideration in promoting the health of populations. It should not be viewed as a new dogma, but rather as the first step in a critical review of the role public health practitioners play currently in sustainability along with actions they can take to improve the situation in the future.

Activity 1.1

Value line: clarifying ideas of sustainability and health

Aim: to help practitioners describe their values in relation to health and sustainability, and to explore ways people with different values can work together.

Description of learning activity

The three-day writing workshop that created this resource book turned out to be a microcosm of the application of the book. The 25 participants crossed two generations and included publi...