![]()

1

Research: Choosing Your Story

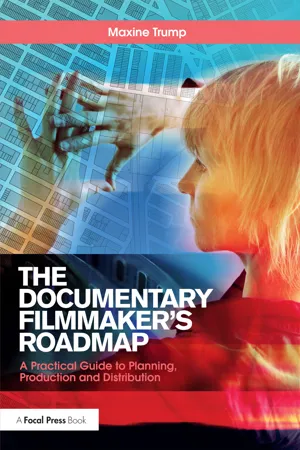

Filmmaking is hard. Know that, recognize it, you are about to embark on a process that you will be committing much of your free time. But, it is the most rewarding work I have ever done. I love the Sean Penn quote, “If it doesn’t end up on screen it will end up in you.” For many of the films I have made I have as many stories to tell about them.

It’s not only a journey of making a film; it will have a profound effect on your life too. So why have you chosen the story you are about to tell? Will it be a story you will remain passionate about for years to come? Is there a story to follow, where things change over time? Can you imagine talking to everyone you know about it? Have you already started? These are all good questions to ask yourself before you start embarking on your film journey. Your why, your need, to make the film, and why should it be you.

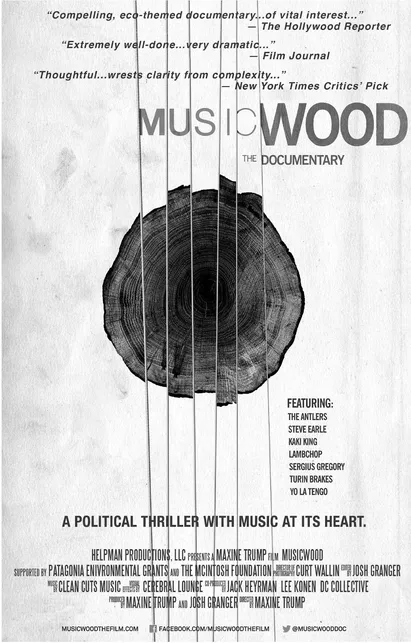

My why for Musicwood was no one was telling this Native American story that was so shocking and surprising, and I was the only one who had access and was willing to give these people a voice. Was it some white colonial guilt that I was itching, making recompense, maybe, mixed in with being always interested in stories about the underdog. Peppered with being very passionate about rain forests, and this huge rain forest in America that no one knew about. And then there is music and fine craft making. Meditative, magical, full of drama and surprise, with a tremendous backdrop. I was in.

FIGURE 1.1 Musicwood theatrical poster

I once heard Kristen Johnson (cinematographer and acclaimed director of Camera Person) talk about the three needs of filmmaking. The need of the person that is being filmed, the need of the person taking the image, and the third need, of those who will be watching these images. All great needs to be conscious of when beginning your research journey, you need all three if you want your film to be seen. The third being just as important as the first and second.

Then what about the first need, the characters themselves, the people in your film. Do they have struggles? Do they want something badly and are actively pursuing it? The adage is very true of “character is action” and “drama is conflict.” You may have to start developing skills where you can tell if a character has charisma. Is there something you can like about them (because you will be spending months of your life with them)?

The filmmaker Robert Greene told Tribeca Film festival that he looks for characters who have layers to their personalities or performative qualities. The director Jesse Moss talks about finding subjects who are natural performers, but also conflicted characters who have strong contradictions and impulses. But the key word is “natural” performers; be careful of people lighting up just for the camera—you don’t want actors in your documentaries unless of course there is a reason for it.

Other filmmakers won’t pick up the camera until they’ve hung out with their characters first. Yet others will do it straight away. Ramona Diaz does test shoots, even filming in moments of silence. Diaz told Tribeca that she considers how characters handle silence as very telling and unpredictability is key. Will your characters surprise you? Chris Hegedus talks about the optimal character being the person who is often risking all to pursue a dream.

Don’t be put off in telling a difficult story. Research the best material, or best contact, that will make the best film. Go to secondhand bookshops, research online articles, of course, but you’ll be surprised what you find from browsing, in libraries, that's how the hugely successful Netflix documentary series Wild Wild Country came about, from researching in libraries. Watch all the videos you can find on the subject—anything that can help inform you about the story you are trying to tell. Talk to people on the phone, be as informed as possible, but don’t be afraid to ask people what they think, or how they can help, or whom they might know. With the best research you will be armed with the easiest access points to your story.

With our last film Musicwood we found characters that we thought would be the people we would follow but they then led us to better characters with more impactful stories. They had more extreme personality traits, or had the most to lose, or the most to gain. So be flexible and listen to your gut instinct; we’re all individual and we may be drawn to different subjects for different reasons—that’s why there are so many different films out there.

With Musicwood, it was going to be a difficult story to navigate: filming in a remote location with inaccessible characters like CEOs of huge US corporations, Native American tribes, tough-as-nails loggers and radical environmentalists.

Heads of companies or CEOs can often be the most media trained, so be aware of that when thinking of following their story. They may not offer the character revelations on camera that make for exciting films. We were lucky in that the head of Taylor Guitars for example, had built his guitar company from scratch. Had so much charisma, was a musician himself but also made himself available to us when we needed to film. Rare for a founder, CEO or president of a company.

As a female white British filmmaker, I hadn’t picked the easiest of stories to tell. A Native American story that brought my own white woman guilt and colonial ancestry to the table. I made sure to reach out to the Native American Museum and other tribal members that weren’t associated with a Native American corporation and asked them to be on my advisory board. We brought on a consultant from one of the tribes early on in production. If we were fully funded at that time, we would have made sure to have a member of production also Native American. We used contacts to make introductions rather than reaching out to the tribes themselves, so there could be a level of trust from the beginning.

Some of our experts in forest ecology were very nervous about the film we were making. They would take a phone call, give me material, or lead us to a great contact but then would quite vehemently tell us our film was a mistake as it could adversely affect this threatened forest. I read a ton of books on the issues presented in Musicwood before I approached specialists on the subject. This way, I didn’t sound like a complete idiot on the phone, and I could express knowledge about the issues. I think this definitely did win over a number of people who were hesitant to talk to us.

Later, when the film was finished, some of these same initial skeptics sent us wonderful emails, telling us it was the best film they had ever seen on the area. That felt amazing.

Remember as you’re researching stories or “casting” characters you are not only building trust with these people but they might become the best patrons for your film, word of mouth is often the best way to get anyone to watch your film, so treat everyone with respect. Whether they will be your antagonist or protagonist in your film.

It can be hard if you are making a film in another country or another state to meet with a character before you shoot. If someone hasn’t recommended them, if you haven’t spoken on the phone with them (which would be incredibly rare) or there are no you tube interviews with them on camera then make sure to fly in early and meet with them before shooting. They may have a great phone voice, but are shy in person and unbearably shy in front of the camera.

You also never want to agree to payment for any participation in a documentary film. The characters will feel compromised and because you are paying them they may very well only tell you what they think you want to hear. It won’t be authentic and you may experience editorial problems because the information isn’t factual.

I like to learn by my mistakes, or at least be prepared for the situation happening again. I like to interview in situ, in the environment that the character dwells in. I say “dwell” rather than “work” or “live” because then it’s open to interpretation, what environment best emulates who your character is everyday or the role they play in your film. Because whatever appears in the shot will be read symbolically by the audience. So if for whatever reason you can’t control the environment, carry some duvetyne (black material that absorbs light, so doesn’t show wrinkles) and clips with you so that you may be able to dress a set quickly. This isn’t ideal but if you’ve had a character that is integral to your film but hard to pin down maybe this is the perfect solution. It keeps the background neutral but black. Not the best backdrop color but if this is the only chance to interview this subject, that you have tried hard to secure then maybe this is your only option. There are also seamless papers that you can purchase, but they are bulky and heavy and not easy to carry.

My favorite films for in situ interviews happen to both be films that involve teenagers: Rich Hill and Racing Dreams. The directors filmed in the teenagers’ bedrooms, in the streets where they hang out, underneath bridges, while they’re smoking, etc. It really gives you a flavor of who the characters are just by the location and what is in the scene.

Marshall Curry talked about casting for Racing Dreams; he spent time with a lot of children before deciding on the three characters he would follow. When casting he would ask them questions about anything else but what he needed for the film to get a sense of their character, bearing in mind they are the film. He would ask questions like: Is their bedroom tidy? or What do they think of God?

And remember sound. Especially in locations. If you want to film scenes externally in South East Alaska (where Musicwood takes place), sea planes are very popular and they make a lot of noise; so do boats. You may have gone to the location to scout in the early evening but what happens at 11am in the morning when you’re trying to film? Are you on a flight path? Is there construction?

Archive or Third Party Materials

Research can also include trying to secure third party materials—that is, any material not owned or shot by you. We explore Fair Use and copywriting etc. in more detail later in the book. When you begin casting characters or speaking to your experts you may begin to start building a research bank of media they have, can send you (or where you might find it) and who owns it.

Start creating a clearance log sheet (see Figure 11.1) and see if they can send you the material straight away. One filmmaker takes a scanner with him to his interviews so that there is no need to chase photos etc., as it can be an arduous process.

If you think you need media from a TV network archives they may have a minimum duration, I had a quote for one piece of archive that would cost US$1,500. An expensive line item in your budget so are there creative solutions you can use that might be the ephemera of the story? What was the weather like that day? Where are we? How are we feeling at this point of the film?

An archive producer can definitely negotiate better rates for you if you do need that certain clip as they have relationships with these libraries. And don’t forget many libraries provide archive material for free—National Archives, Congress—if they are owned by the government. What about government departments like NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)? They provided me with some amazing submersibles footage. If your film is heavy on archive it may be worth spending a day at these libraries in DC. Embassies, The Federal Reserve, President libraries—if you tell them you are conducting research they tend to be more approachable. And at the end of the day it might be cheaper to use a graphic designer and maybe create your own text headlines or simple, low cost, motion graphics.

If there is some great archive online that you can download that gives credence to your argument in the film then that can possibly allow you to use it for free if used correctly. See the chapter regarding “Fair Use” for details (Chapter 11).

![]()

2

Pre-production

I want to start this chapter with some advice, something that filmmakers often overlook: if you want an audience, you have to think of your audience. Now that I work as a consultant, I see filmmakers neglecting to think of this all the time. What do I mean by that? I mean think about who you’re trying to reach. Michael Moore believes that you should never forget that you are entertaining people. I often think of someone who works for Greenpeace; they don’t necessarily want to come home and in their own time turn on a film about forest destruction unless there is a surprising and startling story behind it. If you are passionate about an issue think about how you can tell a story to make people care. This doesn’t mean you can’t be creative, but with feature documentaries we’re trying to get our work widely seen. With short documentaries you have more ability to not work within limitations, and that can be their inventive beauty. I’m not saying box yourself in with your feature, but do consider where you want it to go, and that will help with funding.

Inspiration/Early Analysis and Prep

Marc Singer’s 2000 film Dark Days was the film that made me want to make documentaries. His black-and-white photography, extraordinary characters and access, and DJ Shadow-written score made for a documentary that was extremely cinematic. I honestly don’t think I had seen a theatrical documentary before. It set me on a path of seeking out documentaries that were exciting, electrifying, absorbing, thought provoking and as cinematic as possible.

So when it came time to make Musicwood, my Producer and I constantly analyzed documentaries that we loved. We watched the...