eBook - ePub

Coping With Divorce, Single Parenting, and Remarriage

A Risk and Resiliency Perspective

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Coping With Divorce, Single Parenting, and Remarriage

A Risk and Resiliency Perspective

About this book

In this volume leading researchers offer an interesting and accessible overview of what we now know about risk and protective factors for family functioning and child adjustment in different kinds of families. They explore interactions among individual, familial, and extrafamilial risk and protective factors in an attempt to explain the great diversity in parents' and children's responses to different kinds of experiences associated with marriage, divorce, life in a single parent household, and remarriage.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Coping With Divorce, Single Parenting, and Remarriage by E. Mavis Hetherington in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Why Marriages Succeed or Fail

1

Predicting the Future of Marriages

Sybil Carrère

John M. Gottman

University of Washington

WE ARE INTERESTED in the causal processes that destroy marriage and those processes that build marriage. Our goal is to develop a theory that explains the different trajectories toward divorce and marital stability. As Karney and Bradbury (1995) pointed out, it is not enough to predict divorce or marital stability; researchers must be able to explain why marriages fail or succeed. Our research has discovered some of the pathways that lead to marital dissolution. However, causal factors in marital dissolution is not sufficient information to build a model of functional marital processes. Recent findings in our laboratory indicate that stable, happy marriages are based on a series of marital processes and behaviors that are more than just the absence of dysfunctional processes. Constructive activities build strong marital relationships and help the unions withstand the stressful events and transitions that can destroy weaker marriages. Our goal is to identify both those processes that make a marriage work and those that make a marriage dysfunctional. In this chapter we provide an overview of our research findings and theoretical formulations on the functional and dysfunctional dynamics of marriage.

THE METHODOLOGY OF OBSERVING COUPLES

We have been following 638 couples in our laboratory and in collaboration with Robert Levenson, Lynn Fainsilber Katz, Neil Jacobson, and Laura Carstensen. There are six different cohorts we are studying: a newlywed group of 130 couples (for the past 6 years); a group of 79 couples whom we first saw when they were in their 30s (for the past 14 years); two cohorts of 119 couples with a preschool child at the time of the first visit to our laboratory (for the past 11 and 8 years, respectively); a group of 160 couples, half in their 40s and half in their 60s the first time we contacted them, and half happily and half unhappily married; and a group of 150 married couples who were physically violent, distressed but not violent, or happily married (for the past 8 years). We collected the same core of Time-1 marital assessment data for all our cohorts. Each cohort had additional measures that were specific to the hypotheses associated with the research, but for purposes of this chapter we report primarily on the marital assessment procedures that these studies have in common.

The marital interaction assessment consisted of a 15-minute discussion by the wife and husband of a problem area that was a source of ongoing disagreement in their marriage. This interaction was videotaped with two remotely controlled, high-resolution cameras. The frontal images of the two spouses were combined in a split-screen image through the use of a video special effects generator. Physiological measures were collected during the discussion period and synchronized with the video time code. The couples were also asked to view a videotape of their problem-solving session. During the replay of the marital discussion the couples were asked to rate, in a continuous fashion using a rating dial, how positive or negative they were feeling during the conflict interaction. Physiological measures, video recordings, and data from the rating dial were synchronized and collected during this recall session. We followed these six cohorts over time to assess the stability of the marriages as well as marital satisfaction, health, and family functioning.

Physiological Measures

The peripheral physiological measures we indexed during the Time 1 assessment session were interbeat interval (i.e., the time between the r-spikes of the electrocardiogram; the heart rate is 60,000/interbeat interval), pulse transit time (i.e., the time it takes for the blood to get to the fingertip), finger pulse amplitude, palmar skin conductance, and activity (i.e., gross motor movement). Several of the most recent studies have included ear pulse transit time and respiration. In our study of newlyweds we assayed urinary measures of epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol. We collaborated with Hans Ochs to collect blood assays of immune response in these newlywed couples.

Affect

We primarily used our Specific Affect Coding System (SPAFF; Gottman, 1996) to index the affect expressed by the couples during the marital interactions. SPAFF focuses solely on the affect expressed. The SPAFF system draws on facial expressions (based on Ekman and Friesen’s facial action coding system, 1978), voice tone, and speech content to characterize the emotions expressed by the couples. The emotions captured by this coding system allow us to see the range and sequencing of affect the couples use during their conversations and problem-solving interactions. The positive affects include humor, affection, validation, and joy. The negative affects include emotions such as disgust, contempt, criticism, belligerence, domineering, defensiveness, whining, tension or fear, anger, and sadness.

Problem Solving

We used three observational systems to index problem-solving behavior by couples. We originally used the Marital Interaction Coding System (MICS; Weiss & Summers, 1983). The Couples Interaction Scoring System (CISS; Markman & Notarious, 1987) was later developed in our laboratory to separate the behaviors used in problem-solving sessions from the affect displayed. The Rapid Couples Interaction Scoring System (RCISS; Krokoff, Gottman, & Haas, 1989) is the most recent version of the problem-solving coding system and was created to assess conflict resolution behaviors more quickly. RCISS uses a checklist of 13 behaviors that are scored for the speaker and 9 behaviors that are scored for the listener at each turn of speech. We used the speaker codes to categorize the couples into regulated and unregulated marital types. These codes consist of five positive codes (i.e., neutral or positive problem description, task-oriented relationship information, assent, humor-laugh, and other positive), and eight negative codes (i.e., complain, criticize, negative relationship issue problem talk, yes-but, defensive, put-down, escalate negative affect, and other negative). We computed the average number of positive and negative speaker codes per turn of speech and the average number of positive minus the negative codes per turn.

Oral History Interview

The Oral History Interview is a semistructured interview in which the interviewer asks the couple a series of open-ended questions about the history of their marriage and about their philosophy of marriage. We started using the Oral History Interview in 1986. This interview was developed by Gottman and Krokoff and is modeled after the interview methods of Studs Terkel. The interviewer explores the path the relationship has taken from the first moment the couple met through the dating period, the decision to marry, the wedding, adjustment to marriage, the highs and lows of the marriage, and how the marriage has changed. Philosophy about marriage is examined by having the couple choose a good marriage and a bad marriage they know and describe the qualities of those marriages that make them positive or negative. Finally, the couple is asked to describe their parents’ marriages. Buehlman and Gottman (1996) developed a coding system for this interview that assesses nine dimensions of marriage:

1. We-ness versus Separateness indexes the degree to which a couple see themselves as a unit or as individuals;

2. Fondness and Affection of each spouse for the partner;

3. Expansiveness versus Withdrawal measures how large a role the marital partner and the marriage plays in each spouse’s world view; it is the “cognitive room” an individual allocates to the marriage and to his or her spouse;

4. Negativity Toward the Spouse reflects the disagreement and criticism expressed during the interview by the husband or the wife;

5. Glorifying the Struggle taps the level of difficulty the couple has experienced to keep the marriage together and how they feel about the struggle;

6. Volatility indicates whether the couple experience intense emotions, both positive and negative, in their relationship;

7. Gender Stereotypy is a measure of how traditional or nontraditional the couple’s beliefs and practices are in their marriage;

8. Chaos is linked to whether the couple feel like they have little control over what happens to them;

9. Marital Disappointment and Disillusionment tells us if the couple feels hopeless or defeated about their marriage.

PREDICTING THE MARITAL PATH

We have reached a point in our marital research, across three longitudinal studies, where we can predict with 88% to 94% accuracy those marriages that will remain stable and those marriages that will end in divorce. Some of our earlier studies focused on which couples would divorce (Buehlman, Gottman, & Katz, 1992; Gottman, 1994; Gottman & Levenson, 1992). The older research addresses what is dysfunctional in an ailing marriage, but we have now expanded our research questions to include the etiology of the dysfunctional patterns and what is “functional” in stable and satisfying relationships. Our recent research describes the origins and development of negative affective patterns of communication that predict divorce. This new body of work has also produced findings that reveal the role of positive affect and the nature of conflict resolution in stable and happy marriages. In this chapter we describe the indices of the trajectories toward marital dissolution and marital harmony.

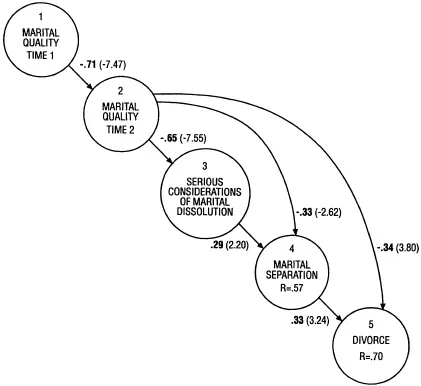

THE CASCADE MODEL OF MARITAL DISSOLUTION

Gottman and Levenson (1992) developed the Cascade Model of Marital Dissolution based on research conducted with 73 married couples who were first brought into the laboratory in 1983. The Cascade Model of Dissolution was proposed, in part, to address the difficulty of predicting divorce in short-term longitudinal studies. Such studies usually have a low base rate of divorce. Gottman and Levenson identified behavioral precursors of divorce with a relatively high base rate of occurrence in marriage. The idea was to predict the entire cascade toward divorce, instead of focusing on only one dichotomous outcome variable. They created a Guttman scale (thus the term cascade) and demonstrated that marriages that are likely to end in divorce travel through the same series of stages. They proposed that, as the marital relationship moves along the trajectory toward dissolution, increasing numbers of these high base-rate variables are exhibited. The Cascade Model predicted the following trajectory toward divorce: low marital satisfaction at Time 1 and Time 2 (1983 and 1987, respectively) → consideration of separation or divorce → separation → divorce.

The data from the study supported the model. In the time period between 1983 and 1987, 36 of the 73 couples (43%) considered divorce, 18 of the couples (24.7%) separated, and 9 of the couples (12.5%) got a divorce. Structural equation modeling of the data indicated that the data were consistent with the Guttman-like ordering of the variables proposed by the cascade model (see Fig. 1.1).

Now the question became, what process variables in behavior, cognition, and physiology, the Core Triad, predicted the cascade? A balance theory motivated the search for predictors (Gottman & Levenson, 1992). The idea was that in the behavioral domain each couple finds a steady state, or a balance between positive and negative affect. With this in mind, the couples were categorized as regulated or nonregulated based on their RCISS data (see the previous discussion for a more detailed description of this coding system for problem-solving behavior). Regulated couples were defined as those for whom both the husband and the wife displayed more positive RCISS codes than negative codes. The nonregulated couples had at least one spouse who displayed either more negative than positive RCISS codes or who had an equal amount of positive and negative codes.

Gottman and Levenson found that the couples in the regulated and nonregulated groups traveled very different paths in their marriages, as indexed by behavioral, physiological, and cognitive markers. The nonregulated couples, compared with the regulated couples, reported more severe marital problems at Time 1 and lower marital satisfaction both at Time 1 and Time 2. These nonregulated couples also described themselves as experiencing poorer health in 1987 than the regulated couples. The physiology of the two groups of wives, but not of the husbands, differed as well. The nonregulated wives had greater sympathetic arousal as indexed by finger pulse amplitude and heart rate. Both of these physiological markers are associated with stress and subsequent risk for disease (cf. Cohen, Kessler, & Gordon, 1995). One can conjecture that the increased sympathetic arousal during the marital conflict sessions is indicative of the pattern of physiological arousal likely to be found in these maritally distressed wives and perhaps causally related to their reports of poor health in 1987.

The rating dial data, a cognitive measure, indicated that these nonregulated couples experienced the marital discussion as a more negative encounter. During the marital interaction sessions the nonregulated couples exhibited more negative emotional behaviors such as defensiveness and whining while also displaying fewer positive emotions such as validation, affection, and joy (SPAFF).

FIG. 1.1. Structural equation model of the cascade model of marital dissolution. From “Marital Processes Predictive of Later Dissolution: Behavior, Physiology and Health,” by J. M. Gottman and R. W. Levenson, 1992, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, p. 227. Copyright © 1992 by the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Adapted with permission.

We learned from building the Cascade Model of Martial Dissolution that there is a continuity between the processes of marital distress and separation and divorce. This work also laid some of the theoretical foundation for understanding which behaviors make a marriage dysfunctional or functional. We also learned that communication patterns with a greater proportion of positive to negative affective and problem-solving behaviors have a stabilizing and healthy influence on relationships.

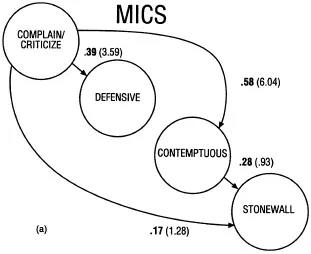

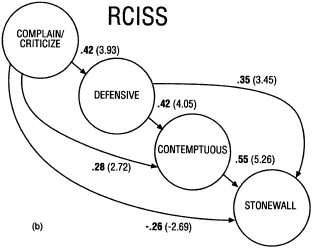

THE FOUR HORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE

The next research question was to ask if all negativity is equally corrosive. Further analyses of the data from the 1983 cohort of couples revealed a behavioral process predictive of marital dissolution. Using both the MICS and RCISS coding systems, Gottman (1993b) constructed structural equation models of this behavioral cascade toward divorce. In both observational systems, criticism led to contempt, which in turn led to defensiveness and subsequently to stonewalling (see Fig. 1.2). Stonewalling is a withdrawal behavior primarily observed in men but associated with physiological arousal in both spouses (Gottman, 1994). The descent through these four behaviors was predictive of divorce and lent further support to the idea of using a Guttman-like scaling model to delineate the stages of marital deconstruction. It was of particular theoretical import to learn that anger, considered a dangerous emotion in marriage by many (e.g., Hendrix, 1988; Parrott & Parrott, 1995), did not predict marital instability.

FIG. 1.2. The cascade behavioral process models using (a) MICS coding and (b) RCISS subscales. From What Predicts Divorce: The Relationship Between Marital Processes and Marital Outcomes, by J. M. Gottman, 1994, Hillsdale NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Copyright © 1994 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Reprinted with permission.

THE DOMAIN OF PERCEPTION: THE DISTANCE AND ISOLATION CASCADE

Another series of signposts indexing the trail of marital instability emerged from the questionnaires used in our research (Gottman, 1993b). A set of five questionnaires outlines the growing distance and isolation the spouses e...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction and Overview

- Part I: Why Marriages Succeed or Fail

- Part II: Child Adjustment in Different Family Forms

- Part III: Family Functioning and Child Adjustment in Divorced and Single-Parent Families

- Part IV: Family Functioning and Child Adjustment in Repartnered Relationships and in Stepfamilies

- Part V: Intervention

- Author Index

- Subject Index