Agrobiodiversity, School Gardens and Healthy Diets

Promoting Biodiversity, Food and Sustainable Nutrition

- 302 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Agrobiodiversity, School Gardens and Healthy Diets

Promoting Biodiversity, Food and Sustainable Nutrition

About this book

This book critically assesses the role of agrobiodiversity in school gardens and its contribution to diversifying diets, promoting healthy eating habits and improving nutrition among schoolchildren as well as other benefits relating to climate change adaptation, ecoliteracy and greening school spaces.

Many schoolchildren suffer from various forms of malnutrition and it is important to address their nutritional status given the effects it has on their health, cognition, and subsequently their educational achievement. Schools are recognized as excellent platforms for promoting lifelong healthy eating and improving long-term, sustainable nutrition security required for optimum educational outcomes. This book reveals the multiple benefits of school gardens for improving nutrition and education for children and their families. It examines issues such as school feeding, community food production, school gardening, nutritional education and the promotion of agrobiodiversity, and draws on international case studies, from both developed and developing nations, to provide a comprehensive global assessment.

This book will be essential reading for those interested in promoting agrobiodiversity, sustainable nutrition and healthy eating habits in schools and public institutions more generally. It identifies recurring and emerging issues, establishes best practices, identifies key criteria for success and advises on strategies for scaling up and scaling out elements to improve the uptake of school gardens.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

SCHOOL GARDENS

Multiple functions and multiple outcomes

Introduction

School gardens: a short history1

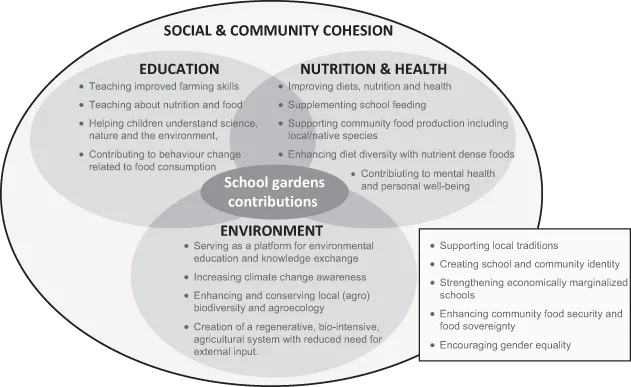

The multiple benefits of school gardens

Development of agricultural and livelihood skills including knowledge of sustainable food systems

BOX 1.1: SOILS FOR LIFE

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of boxes

- Acknowledgements

- List of contributors

- List of abbreviations

- 1 School gardens: multiple functions and multiple outcomes

- 2 Schools as a system to improve nutrition

- 3 Strategies for integrating food and nutrition in the primary school curriculum

- 4 Linking school gardens, school feeding, and nutrition education in the Philippines

- 5 School gardens in Nepal: design, piloting, and scaling

- 6 Trees nurture nutrition: an insight on how to integrate locally available food tree and crop species in school gardens

- 7 The role of school gardens as conservation networks for tree genetic resources

- 8 The impact of school gardens on nutrition outcomes in low-income countries

- 9 Parent engagement in sustaining the nutritional gains from School-Plus-Home Gardens Project and school-based feeding programmes in the Philippines: the case of the Province of Laguna

- 10 Scaling up the integrated school nutrition model in the Philippines: experiences and lessons learned

- C1 The Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden Foundation Program

- C2 Reviving local food systems in Hawai‘i

- C3 Food Plant Solutions: School gardens in Vietnam

- C4 Preserving local cultural heritage through capacity building for girls in the Moroccan High Atlas

- C5 Learning gardens cultivating health and well-being – stories from Australia

- C6 African leafy vegetables go back to school: farm to school networks embrace biodiversity for food and nutrition in Kenya

- C7 Grow to learn – learning gardens for Syrian children and youth in Lebanon

- C8 School gardens (māra): today’s learning spaces for Māori

- C9 Intergenerational transfer of knowledge and mindset change through school gardens among indigenous children in Meghalaya, North East India

- C10 Laboratorios para la Vida: action research for agroecological scaling through food- and garden-based education

- C11 Agrobiodiversity education: the inclusion of agrobiodiversity in primary school curricula in Xiengkhouang Province, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic

- C12 Katakin kōṃṃan jikin kallib ilo jikuul – Republic of the Marshall Islands School Learning Garden Program

- C13 Where the wild things are

- C14 Slow Food 10,000 gardens – cultivating the future of Africa

- C15 The integration of food biodiversity in school curricula through school gardens and gastronomy in Brazil

- Index