CHAPTER One

Developmental issues in the etiology of personality disorders

The definitions of personality disorders in the DSM help us to form a clinical picture of how enduring and ego-syntonic psychopathology arises. This multi-axial system is the basis of and framework for classification in American empirical psychiatry.

This methodology has some disadvantages. In order to separate personality disorders from clinical syndromes, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has had to opt for an empirical epistemology designed to allow communication between clinicians of varying disciplines. However, this has meant giving up a whole heritage of knowledge that has been constructed over the last century, that of traditional psychodynamic and developmental epistemology. The DSM may well allow us to diagnose from verifiable observation, but it is of no use when it comes to understanding the etiology and the psychic function of a personality disorder.

These pathologies seem to be sufficiently specific in character for us to be able to distinguish them from Axis I disorders, and place them on Axis II. Let us examine their characteristics: they are generally present from early adulthood, tend to be ego-syntonic, and appear in a variety of contexts. They are woven into the very identity of the person: hence their name of personality disorders. Since these are intimately connected with the identity of the individual, we must understand that the person is immersed in what both defines him and is also the source of his suffering. Nowadays we cannot approach these complex structures of identity in a one-dimensional manner. Personality disorders are the result of several etiological factors, of nature and of nurture, genetic and psychological, as well as risk and resilience factors, present in the person and in his developmental environment.

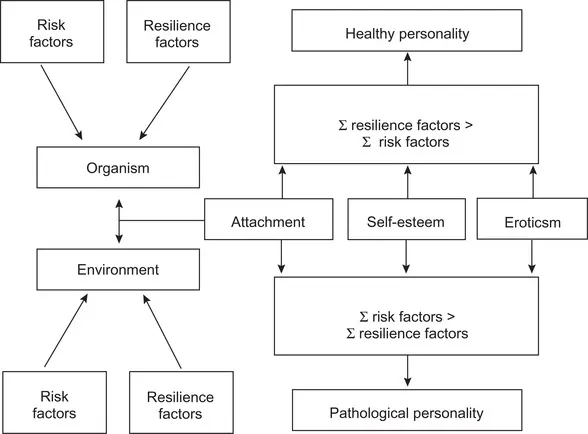

It seems that as our knowledge of development has increased, each of the areas of study or perspective necessary to our understanding of personality disorders has developed parallel to each of the others. Recently, attempts towards a dialogue have been established between these different perspectives; however, we are still a long way away from a synthesis of theories of socialization, psychodynamics, and applied neuroscience. Nevertheless, it is possible to design a hypothetical model of the system of interactions between factors implicated in the development of personality and in the pathogenesis of personality disorders. This is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Multi-factorial development.

Let us suppose that the development is a field phenomenon (Lewin, 1951), in the Lewinian sense, that is to say that the individual is subject to the convergence of a multitude of forces that make him who he is. This developmental field is where the psychophysiological organism, the becoming person, meets the environment: human, physical, economic, social, and cultural. The psychophysiological organism is mobilized through an individual’s genetic programme and through a human evolutionary blueprint. In chapter Three we will look more closely at early developmental influences and drives. Whatever the original drive of the organism it must develop in a multifaceted and multidimensional environment. One might say that development results from the interaction between the organism and its environment. But, each of the two poles of the organism-environment field carries elements which Lewin might have labelled accelerators or brakes. These either encourage or hold back development. Drawing on the ideas of Boris Cyrulnik (2000), we call the brakes “developmental risk factors” and the forces of acceleration “resilience factors". From this we can make out a matrix of interactions between four groups of forces in the developmental field.

Into the group named “risk factors inherent in the organism”, one might add character styles, which are the subjects of contemporary study, and could be linked with the appearance of a personality disorder. Character is defined as being one’s style of behaviour. Thus, character does not determine what one does (behaviour) nor why one does it (motivation), but how one does it (Cloninger, Svrakic & Przybeck, 2000). What should we understand by “genetic singularity of character"? By way of example, Cloninger, Svrakic and Przybeck identify four interacting character traits that give each person his personal temperamental style. These are the avoidance of pain, seeking novelty, dependence on reward, and persistence.

Panksepp (1998) names four major systems that organize emotion: the search for pleasure and enjoyment, anger and rage, fear and anxiety, panic and distress. These systems are evolutionary. At the dawn of time, they were necessary for the survival of the individual and of the species. They are “economical” in the sense that they permit an automatic response to biologically significant events. People’s individual character styles come from constitutional variations and differences between individuals.

As a result of research on genetic inheritance, we have been able to connect certain character styles with various personality disorders.

Thus we can say that inherited characteristics may constitute both a mixture of risk factors and resilience factors inherent from birth in the psychophysiological organism.

The same is true of the environment which also carries a particular configuration of risk and resilience factors: parental mental and physical health, living conditions, education, social and political upheavals, etc. Therefore, in each chapter on the major developmental issues we will be taking account of these risk and resilience factors.

Thus, development is a result of the meeting between a psychophysiological organism and its environment, each of which carries risk and resilience factors. The growing Self develops by taking in this environment, firstly through parental figures, then by contact with the wider environment, which is less mediated by the parents. Likewise, endowed with an evolutionary blueprint, the little human being has the tools necessary for movement, for grasping and using objects, for walking and talking. If his/her genetic potential carries a greater ratio of resilience to risk factors, s/he will have a greater chance of accomplishing these tasks. The same is true of the environment. The little human being will achieve more if his/her environment carries more resilience than risk factors.

But what needs to be achieved? The task is vast! Firstly, to become a person. At best, to become a person equipped with the ability to live their life, having extracted the vital substance from life experiences and having eliminated from these same experiences that which is toxic. There exist many theories as to the diverse resources and skills that will give a person the physical health and robustness necessary for accomplishing their potential. Some people suggest that the basis of mental health is emotional security. Others speak of narcissistic balance, yet others of ego strength. Finally, some follow Freud and put it all down to two fundamental abilities: to love and to work (Erikson, 1968).

I propose that we organize these multiple tasks around three main developmental areas: attachment, self-esteem, and eroticism. This perspective allows us to bring together a broad background of knowledge resulting from infant and early childhood observation, case studies of adult psychotherapy patients as well as empirical and theoretical research.

Over and above any disagreements and semantic differences, this proposed organization of various strands of knowledge about developmental processes allows us to be able to draw upon a clinically useful body of knowledge without engaging in any theoretical conflict. We can now put forward the framework for the rest of our discussion: psychic development is a field phenomenon where a psychophysiological organism meets an environment and this field contains both risk and resilience factors. It takes the shape of a developmental path whereby there are three major developmental tasks that need to be accomplished. Thus we can state that personality disorder is a result of a failure to complete one or several of the developmental tasks and that the signs of this unfinished business can be observed in the phenomenology of a specific pathology. We can establish the following hypothesis: the inability to complete a particular developmental task results from a configuration of the developmental field that can be expressed in the equation:

The sum of the risk factors > the sum of the resilience factors = personality disorder.

In other words, the sum of the risk factors in the developmental field, in both organism and environment, is greater than the sum of the resilience factors.

This would equate with the ongoing observations that most clinicians make. We see people who come from an apparently supportive environment, who in adulthood are obviously suffering from a personality disorder. Conversely, we meet those who have lived in an extremely deficient environment, who are perfectly healthy.

Since the publication of Cyrulnik’s work, we have a better understanding of resilience factors which, alongside the more easily recognized risk factors, play a part in each individual’s specific developmental trajectory. If the developmental pathway can be seen in this light, and we accept that personality disorder is the result of a preponderance of risk over resilience factors, organic as well as environmental, we are in a better position to understand the ability of the healthy adult to manage the ups and downs of existence without a build-up of serious mental illness.

Getting through infancy with an embryonic form of an adult Self is the result of passing a series of tests, of resolving a series of enigmas or developmental problems which will inevitably occur at various stages as the person matures. We will give the name developmental issues to each of the axes of maturation, which begin in early infancy, and which prepare us to face the great existential questions: How shall I survive? What of the Other? Why trust? How shall I love or hate? How and why shall I leave? How and why shall I stay? How can I be free and committed, free and attached? And many other questions!

The psychological function of the developing person can be represented metaphorically as the psyche’s immuno-metabolic system. It is therefore the psychic equivalent of the digestive, metabolic, and immune systems. Its job is to take from the environment the psychic nourishment necessary to ensure health and continuing development. One can have “favourite foods”, for example, solitude, without becoming schizoid. But no one is perfectly safe and immune from everything. Each personality contains, beyond simple preferences, specific vulnerabilities (uncertainty for the obsessive; isolation for the dependent, and so forth).

The personality develops in a way that requires it to resolve, as best it can, a certain number of developmental issues. Good psychological functioning results from the resolution of each of these issues (Johnson, 1994).

Adulthood is therefore characterized equally by a broad and flexible menu of “favourite foods” or sought-out experiences that have been absorbed, and by a capacity to metabolize life’s events in a way that extracts vital energy. This flexibility and maximum resolution of issues does not mean that there will be no sadness, no uncertainty, no tension and confusion in our lives, and neither will we necessarily be nice, affectionate people. It simply means that the personality is sufficiently exempt from structural defects and does not produce serious endogenous clinical problems such as depression, hypochondria, etc.

This said, even well-supported people may suffer situational psychological problems that require professional intervention. This may happen, for instance, if stress factors are so intense that the metabolic and immune systems of the psyche are overwhelmed. Anyone can get food poisoning without having a structural malfunction in the digestive system.

Pathology in the structure of the personality is the consequence of a setback in one or more developmental areas. The pathological personality is characterized not only by a serious deficit in its “digestive, metabolic, and immune” capacities, but equally by the fact that these deficits mirror a person’s preferences or “favourite foods": the narcissist wants constant praise yet he metabolizes it as though it were envy and thus confirms an affective isolation where appreciation from another person is never nourishing. In adulthood, one or more incomplete developmental issues seem to persist. The person tries to configure his world so that these issues can be resolved. Yet, instead of resolving them, he keeps finding himself at an impasse. This impasse is paradoxical because it is painful yet it also pre-configures the world according to previous experiences: I am in pain, but at least life is not absurd and senseless, for this experience is familiar.

One recognizes the unconscious need of the paranoid personality to be betrayed, for the narcissist to be envied, for the dependant to be abandoned. In short, a developmental issue lies dormant. These developmental issues are crucial and linked indissolubly to the human condition. When one of them cannot be completed, the experience of rupture or of failure for the young child is totally intolerable. This is why, in adulthood, the person suffering from a structural personality disorder must not let himself know the deep nature of the issue and its incompleteness. The paranoid does not recognize his need to be betrayed, the narcissist does not know why he needs to be envied, and the dependant has no suspicion of his need for abandonment. Rather, each of these experiences is consciously abhorred.

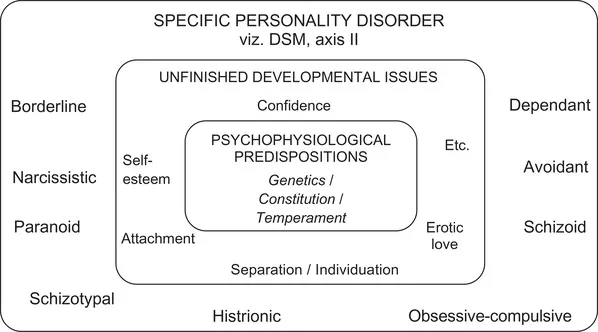

Figure 2 is a diagram of the relationship between the original organism, the early human environment, the developmental issues, and the personality disorder.

On the basis of this diagram, it is very tempting to make unequivocal links between a given issue and a specific pathology: confidence issue = paranoid personality; self-esteem issue = narcissistic personality, etc. We must resist the temptation to do this. Anyone who has worked over time with people presenting with personality problems knows that things are not that simple. Often we find that behind a narcissistic personality, for example, hides an absence of basic security, which a stable and reliable parental figure would have provided. The apparent narcissism compensates for the inability to connect with a reliable Other. The person seeks admiration in order to induce the other to fuse with him. In this way, the desire for the Other is an ersatz attachment and a psychic prosthesis—an artificial limb whose role is to fill the void.

Figure 2. Developmental issues and personality pathology.

Thus, in personality disorders, a developmental issue lies fallow. It is unfinished, in the Gestalt sense of the word. We would be wrong to believe that this old issue has become an archaeological site, suspended in time because work has stopped.

In fact, the person carries this unfinished issue because it is indispensable to him. He is bound to keep finding it in significant areas of his life. Not only does he give personal significance to life events, as cognitive psychology teaches us, but he still goes about actively re-creating conditions that parallel the themes of what is unresolved. Thus he sets up situations where incomplete developmental themes recur. He is confronted anew by the complexity and the pain of attachment, of self-esteem, of separation, of individuation. The person who presents with a personality disorder produces and reproduces, time and again in his life, impasses that are not simply a result of a misreading of reality. These impasses are happening in the here and now. They are real events and experiences, lived within relationships that are equally real.

So, what is the function of these impasses, largely produced and given meaning by the person himself? To understand this, we must understand that a developmental issue lies dormant because it cannot be completed in any conscious way. In fact, a question and a problem still remain, waiting for a response. Instead of consciousness and experiential completion we have dilemma and impasse. In other words, in adulthood, the person keeps returning to the unresolved dilemma and to the subjective distress that accompanied it. Here is the paradox: pain from the past is felt again in the present and deplored, but is cut off from its significant origin, and the person is conscious of nothing apart from having to endure it. Yet at the same time, this pain carries with it a kind of consolation: it gives a sense of being alive. The paranoid may be in considerable distress, surrounded by malevolent people, yet this malevolence makes life predictable, it makes sense of his vigilance and gives it a purpose.

We will not dwell on the so-called masochism of the repetition co...