- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Urban Tourism and Urban Change: Cities in a Global Economy provides both a sociological / cultural analysis of change that has taken place in many of the world's cities. This focused treatment of urban tourism examines the implications of these changes for urban management and planning sense, for success and failure in metropolitan change. Uniquely suited for teaching purposes, Costas Spirou integrates numerous case studies of cities to illuminate the significant impact and promise of tourism on urban image and economic development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Urban Tourism and Urban Change by Costas Spirou in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Holocaust History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Changing Cities and the Commodification of Leisure

During the second half of the twentieth century, the rise of the suburbs and ensuing problems in the inner cities, especially during the 1960s and 1970s, caused significant geographic restructuring along with major changes in social relations. This book focuses on one aspect of that restructuring; namely, the role of urban tourism in the revitalization of downtown areas and the surrounding neighborhoods. Specifically, how the intersection of “a second iteration of leisure,” a condition that emerged during the post-World War II era, coupled with urban economic development initiatives contributed to major investment in urban infrastructure and the marketing of cities as places of entertainment and play for both those who are on vacation and those who are visiting for business reasons.

These culture-driven strategies in urban development were fueled by the fact that citizens now have more leisure-expendable income than ever before. This prompted city governments to increase expenditures on culture and specialized bureaucracies. In order to cater to a growing, more sophisticated, and differentiated public demand, policy-making bodies ventured to enhance their provision of cultural services. The outcome of these trends resulted in the development of an economy of urban tourism. Thus, we can observe cities and their governments turning their attention to showcasing their heritage and exporting their cultural identity, with hope of translating these policies into revenue streams capable of bringing about social and economic transformation.

This investigation of the rise and importance of urban tourism is structured around four key interlocking themes so that the topic can be understood via a developmental perspective within a broad historical and socioeconomic framework. First, postwar urban restructuring forced cities to search for alternative means of economic development. Rapidly evolving elements of globalization furthered this quest by injecting competition between cities (for business and recreational visitors), and leading them to embrace a variety of entrepreneurial strategies. Second, the emergence of urban tourism as a fiscal growth strategy reorganized the physical landscape of cities. The massive development of infrastructure that followed changed the built environment in ways not visible since the early period of city building, evident during the latter part of the nineteenth and early years of the twentieth centuries. Third, the remaking of the urban core through tourism also altered the culture of cities, attracting younger workers. Increased cultural amenities, for example, drew greater numbers of people who worked in the arts at all levels to urban areas. Fourth, some of the implications associated with the rise of urban tourism included questionable social and economic benefits, diversion of valuable resources, and the difficulties of sustaining a dual city that catered both to visitors and residents, a system which tended to aid the interests of the corporate elite.

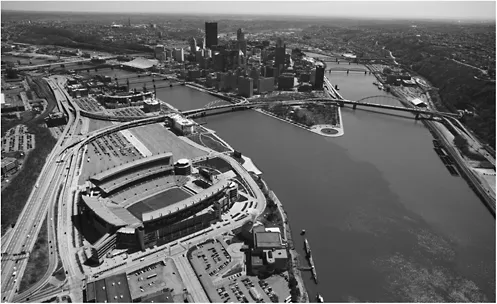

The issues outlined above are demonstrated by the city of Pittsburgh. At the turn of the twentieth century Pittsburgh was on top of the world. The city was synonymous with steel production, providing more than a third of the total national output, exemplifying the prowess of the American economy in the midst of major industrial growth. By 1950, Pittsburgh had the highest population in its history. The professional football team, the Steelers, and the locally produced Iron City Beer, reflected the cultural integration of the city’s manufacturing identity. However, Pittsburgh’s fortunes were soon reversed. Once it had been the steel capital of the world, but massive declines in manufacturing jobs, which caused significant depopulation, led to the disintegration of the local economy following extensive plant closings. Many neighborhoods were ravaged, especially in the north side of the city. There were empty factories with rows of smokestacks and a vast array of vacant buildings, commercial and residential. During the 1970s the city’s population declined by almost 14 percent and in the 1980s by more than 18 percent. Equally significant was the weakening of the corporate leadership which had played a critical role in the city’s earlier industrial development.1

But in May of 2009 the White House, to the surprise of many, announced that the city would serve as the site for the September 2009 G-20 Economic Summit. It was Pittsburgh, rather than New York or Chicago that was to be presented as a shining case of a previously depressed manufacturing center that had managed to successfully revitalize itself into a postindustrial city. One indicator of Pittsburgh’s reversal of fortune was the national and international attention it received as the recipient of numerous accolades for livability. In 2005, The Economist ranked it as the most livable city in the United States and 26th worldwide. In 2007, Places Rated Almanac recognized it as “America’s Most Livable City”2 and in 2009, The Economist placed Pittsburgh once again in the number one position nationally and 29th worldwide.3 In 2009, Forbes Magazine ranked it as America’s 10th most livable city among 379 contenders. Of the five indicators used (income growth, cost of living index, culture index, crime rate per 1 million residents, and unemployment), Pittsburgh received the highest mark in the culture index (37 of 379 competitor cities). In 2010, the same publication identified Pittsburgh as the most livable city in the country, giving it a ranking of 26th in arts and leisure among the country’s 200 largest metropolitan areas.4

This renaissance can be attributed to many factors. Since the mid-to late 1990s, Pittsburgh had pursued a diversified economy. Focus had been placed on upgrading local business conditions by attracting companies in the healthcare and medical sectors, technology, robotics, and financial services. In addition, institutions of higher education like Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh improved their status, helping advance the city’s new image.

But Pittsburgh also saw itself as a regional recreational and convention destination. City officials endeavored to build an infrastructure that would support the advancement of this industry and significantly upgrade its current standing. For example, the David L. Lawrence Convention Center, opened in 2003, is owned by the Sports and Exposition Authority of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County. The $375 million facility was developed as a result of a public–private partnership that included philanthropic contributions and corporate sponsorships with the state providing more than $150 million. Viewed as the keystone of the hospitality industry in western Pennsylvania, the riverfront project, which offers more than 1.5 million square feet of space, replaced the previous convention center, which had been built in 1981 and had just 130,000 square feet.

The construction of the convention center is the result of a new strategic direction and an ambitious financial framework that was introduced in 1997. Revenues were drawn from various local sources, but all were for the benefit of restructuring the city. They included adding a 1 percent county sales tax on top of the existing 6 percent base sales tax, as well as parking, hotel/motel taxes, federal and state contributions, and even a payroll tax on nonresident athletes. The result of this initiative was the unveiling of the Regional Destination Financing Plan. Introduced in 1998, the plan included over $1 billion in development projects.

In addition to the convention center and related infrastructural costs, a large portion of these funds went to the construction of new sporting facilities on the North Shore, an area where Three Rivers Stadium once hosted the city’s professional baseball and professional football teams. Demolition of the old stadium made room for two separate structures, PNC Park (home of the Pirates) and Heinz Field (home of the Steelers). City officials then looked beyond sports. According to then Mayor Tom Murphy there was a need for a park that would “be visually attractive, but also have the feel of an adventure playground, so that families would bring their kids there.” The $31 million North Shore Riverfront Park introduced greenery and connected the North Shore with the downtown, bringing more people to the once barren area. In fact, such development prompted one observer to exclaim that “the new amenities have bolstered the city’s mood…I think people

Figure 1.1 Aerial view of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The North Shore (foreground) includes concentrated investments in the development of the Carnegie Science Center and the UPMC Sports Works, Heinz Field, PNC Park, the Children’s Museum, the Andy Warhol Museum and the National Aviary. The addition of parkland and bridges connects these attractions to the downtown, including the Cultural District and Point State Park (Courtesy Io Foto, Shutterstock Images).

have begun to see that life after steel is possible. All the old industrial detritus around here is gone.”5

Pittsburgh’s array of projects was intended to recast the downtown as a premier location for tourists, businesses, residents, and for those seeking entertainment opportunities. A number of organizations led the charge. The Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership, formed in 1994, marketed the area as a vibrant location for visitors and locals. The Urban Redevelopment Authority directed the revitalization of downtown by introducing Three PNC Plaza ($133 million) and Piatt Place ($70 million), two mixed use projects that provide office and retail space, a hotel, and condominiums. In addition to these facilities, the $40 million, state of the art August Wilson Center for African American Culture, parks, and high rise residential structures, also helped change the image of the core.

These investments proved to have a powerful impact. The once dominant view of the city was being altered right in the midst of an ongoing population exodus. The number of young people had drastically diminished with a high ratio of elderly residents staying behind. However, one 2006 analysis identified a reversing trend, concluding that among “Pittsburghers 25–34 years old, 41.9% have graduated from university, placing the city among America’s top ten. More than 17% of those young people have also earned an additional graduate or professional degree: the fourth-highest share in the country, behind only Washington, DC (think lawyers), Boston and San Francisco.”6 The 2007 to 2008 estimated annual population loss was by far the smallest in this decade.7

The city sought to retain this younger and highly educated group. For example, The Propel Pittsburgh Commission is a mayoral committee whose mission is to give “young professionals of Pittsburgh a major role in moving the City of Pittsburgh forward.”8 Its interest for the creative class, or knowledge-intensive workers, was combined with industrial brownfield site redevelopment.9 A good example of that is the SouthSide Works complex which opened in 2005 and is a 34-acre project, once the site of an old Jones and Laughlin steel plant along the Monongahela River. The neighborhood built at the site includes upscale ethnic restaurants, high end apartments, art galleries, shopping outlets, along with an extensive array of entertainment opportunities. The development also complements the East Carson Street business district, aimed at serving young professionals who can combine living, working, and playing within its boundaries. Future plans include a riverfront pavilion and a fitness center.10

It is clear from the case of Pittsburgh that cities are reorganizing themselves by utilizing cultural strategies to craft new urban identities, employing numerous initiatives aimed at reviving and growing their local economies. In response to fiscal pressures and other, larger socioeconomic structural changes, cities have aggressively embarked on plans to reinterpret or romanticize their past. In turn, they are endeavoring to replace former identities by constructing and promoting new, culturally based images that rely on entertainment, leisure activities, urban tourism, along with convention business. Museums, festivals, revamped public spaces, tourism bubbles, sports stadiums, theater districts, ethnic precincts, convention centers, and urban beautification programs are some of the tools utilized to advance this new direction.

To better understand these significant developments, it is important to first focus on the conditions that helped propel the reorganization of American cities into places of culture, leisure, and entertainment. I provide a treatme...

Table of contents

- METROPOLIS AND MODERN LIFE

- Contents

- Series Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Changing Cities and the Commodification of Leisure

- 2 Globalization, Urban Competition, and Tourism

- 3 Tourism Policies and Urban Growth

- 4 The Infrastructure and Finance of Urban Tourism

- 5 Urban Tourism, Amenities, and Human Capital

- 6 Residential Development and the New Face of Downtowns

- 7 Implications and Debates

- Notes

- Index