- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

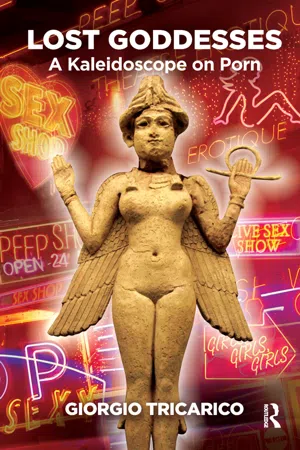

About this book

Porn is a complex symbol of our current world, and a shining example of the 'Shadow' of the Western culture. While many books essentially show its negative sides, the risks of addiction, the danger of damaging the relationship between sexes, and so on, this work focuses on porn as a phenomenon of our times, exploring its several colours, and trying to capture its inner logic and essence. Despite its pervasive ubiquity in the internet and in the lives of many, porn is apparently the ultimate taboo in the consulting room: in fact, very rarely does a patient mention something detailed about his or her use of porn. In parallel with its growing presence, the last forty years have witnessed a significant growth of publications about porn. The present work aims at deepening some aspects of internet porn from the perspective of Analytical Psychology, seeing it as symbol of the complexity of the human psyche, emerged in a specific moment of the history of consciousness.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lost Goddesses by Giorgio Tricarico in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Porn and technology

Acommon anecdote narrates that five minutes after photography had been invented, in 1826, a woman was posing naked in front of the photographic lens. The same is said to have happened some decades later, when cinematography came to light. It might sound pretty trivial to underline it, but porn owes its very existence to the development of technological devices.

Camerae obscurae, daguerreotypes, monochrome and colour photography, together with the invention of the motion picture, made sexually explicit pictures and short movies possible by the end of the nineteenth century.1

The chance to get hold of such materials, however, was pretty scarce for the largest part of the population of Western countries, this novelty being available only for minorities and elites for several decades.2 From the 1950s onwards, though, eight-millimetre films and cine-cameras gave impetus to a growing production of erotic movies, shot in black and white, but these largely remained outside the mainstream movie industry until the 1960s. It was during this decade that sexually explicit material started circulating more and more, in the form of magazines and movies, in an interesting parallel with other significant social changes. In fact, this rapidly growing phenomenon mingled with the subversion of bourgeois morality and values, the feminist struggle for equality, and the separation of sexuality from the reproductive function.

The production of black-and-white porn movies flourished in Soho, London, from the beginning of the 1960s, and was to find a more permissive environment of potential consumers in Denmark, which subsequently became a leading producer of porn material, together with Sweden.

As previously mentioned, in 1969 Denmark was the first country to legally allow the production and the distribution of hard-core movies and pictures, followed by the United States in 1970. Mass porn could be considered to have been born with these legal acts, as from that moment on, it was more and more possible for everyone to get in touch with porn material, buying magazines in some newspaper kiosks and watching movies in the new-born porn-movie theatres.

The next technological step was going to be the invention of VCR (Video Cassette Recording) systems, which started in the middle of the 1970s, to reach their boom in the early 1980s. Actually, VCR systems became popular and widespread precisely due to hard-core VHS videotape sales.

Dominating the Western market until the mid-1990s, a VHS tape made it very simple to view porn at home, avoiding the difficulties and possibly the social shame of physically going to public places like movie theatres. Renting or buying porn videotapes became more and more handy, while VHS functions such as forward, rewind, and slow motion changed the approachability of porn movies. Thanks to these functions, it was possible to skip all the unnecessary acting in order to reach directly the favourite sex scenes, and to go back to them any time one felt like it.

DVDs substituted VCR technology during the 1990s, but the accessibility of porn material did not change significantly, until the World Wide Web took over. Although it is still possible to buy porn DVDs and magazines, the internet enables the viewing of porn material online, just by connecting computers, tablets, and mobile phones to one of the thousands of free porn websites, such as xvideos, pornhub, or youporn.

In fewer than forty years, therefore, we have witnessed a tremendous increase in the reachability of porn material, together with its progressive dematerialisation, from paper magazines to videotapes, from DVDs to video files. This dematerialisation has gone hand in hand with the decreasing need to physically go and look for porn materials; walking gingerly to a newspaper kiosk, a sex shop, or a movie theatre was gradually replaced by the discreet purchase of DVDs online, subscription to a pay-per-view TV channel, and eventually to accessing porn files in streaming for free, safely sitting on one’s own couch with a tablet or a laptop. Furthermore, the web evolution has made it possible for people to become active users, and not only passive consumers, as it is nowadays quite simple for basically everyone to shoot porn pictures or videos and upload them in video file format online.

This short survey of the different phases in the production, the distribution, and the accessibility of porn material aims to underline how porn and technology have been deeply entwined with each other since the very start. Hence, porn must be considered a technological product. This product is currently codified in immaterial files, infinitely duplica-ble, reproducible, and so subject to the logic of several other products developed in our technological society.

Speaking of technology, it would be remiss to prescind from the critical work of the German philosopher Günther Anders.3 After a deplorable delay of thirty-five years, a first English translation of the second volume of his main work has finally appeared on the web, together with some extracts from the first volume, the publication of which dated back to 1956.4 Reversal of perspective is the peculiar way to proceed with Anders’ “philosophical anthropology in the epoch of technocracy”, as he himself defines it. This reversal first of all implies that it’s no more possible to ask ourselves what we can do with technology, rather we should ask what technology can do with (or to) us. Anders maintains that:

the world in which we live and which surrounds us is a technological world, to such an extent that we are no longer permitted to say that, in our historical situation, technology is just one thing that exists among us like other things, but that instead we must say that now, history unfolds in the situation of the world known as world of technology, and therefore technology has actually become the subject of history, alongside of which we are merely co-historical.(Anders, 2007b, p. 3)

Technology is the current subject of history, the zeitgeist of our time, and our fate.

The system of apparatuses is our world and we, as individuals, are undergoing transformations in our psychic, emotional, and ethical way-of-being, still to be focused on and explored.

If we define the second industrial revolution as the period during which machines started being produced by way of other machines, its outcome is a world where the production of products corresponds to the production of means of productions, that in turn produce other means of productions, and so on, until final products are created.

These last are no more means of production but means of consumption. Their consumption produces the situation in which the production by way of machines is required and necessary.

Our role is hence to use and consume products so that the production can continue. Products have a hunger to be consumed, so to say, and in order to fulfil this hunger, we need to have a need for them.

But since this need does not necessarily arise naturally in us, it has to be produced as well. The third industrial revolution implies the production of needs in us, by way of a specific industry, that is, advertisement or, more elegantly, marketing, and by way of the products themselves, in as much as they are capable of inducing the need in us by way of their use and consumption, and by way of programmed obsolescence, so that the production will not stop. In the meantime, the technological apparatus as a whole keeps growing, in terms of potential to infinitely expand and to reach goals, following the commandment “Everything that can be done, must be done”. One barely visible result is that we all are transformed in some sense into unpaid employees of the technological apparatus, so that it continues to expand itself and to function, that is, to produce.5

These are some of the coordinates of the epoch of the third industrial revolution, according to Anders’ view. In such a world, technological inventions are never just technological inventions,6 because

every machine, once it exists, already constitutes a way of its utilisation by the mere fact of its functioning […] We are always molded by every apparatus, regardless of the purpose for which we think of using it or imagine it being used for […] since it always presupposes or estabilishes a determined relation between us and our kind, between us and things, between things and us.(Anders, 2007b, p. 200)

The idea that technological inventions are just neutral tools, and all that matters is how we use them, is dismissed as a naivety to be openly fought, a mere illusion, probably aimed to preserve our faded freedom from the system of apparatuses that we have built and currently inhabit.

Having something compels one not only to use it, but to need it: in the end, one does not have what is useful, but what is imposed.

The example of Coca-Cola, given by Anders, could clarify the insidious inversion implicit in our common use of technological products. Thirst is definitely a basic need, but we cannot say that thirst for Coca-Cola is. The tendency of thirst to be directed towards Coca-Cola and not to water is due to the fact that the effect of Coca-Cola is exactly to stimulate thirst, precisely a thirst for Coca-Cola.

The need is essentially produced by the product itself, together with the massive influence of advertisement and marketing. The need produced by the product ensures the increase of the production of the product, via our cooperation as consumers/employees.

The need to be permanently connected is a flawless example of the same principle, updated to our current times. Surely we cannot say that being permanently connected is a basic need, like hunger, thirst, or sexuality. Still, the evidence of thousands of people, bowing to the screens of their mobiles and tablets in trains, in metros, in bars, or walking on the street, should suggest that the need to be permanently connected has been absorbed by the majority of us.

The production of more powerful devices, of their accessories, of thousands of constantly implementing apps, have the biggest supporters precisely among the users, bona fide convinced that they are only using tools that expand their own freedom to express themselves, and that make their own lives more comfortable or entertaining.

As Anders aptly summarises,

a considerable part of today’s commodities are not actually there for us; instead, we are ourselves, as buyers and consumers, those who are there to assure their further production. Thus, if our need to consume (and, as a result, our lifestyle) has been created—or at least marked—so that commodities can be sold, we are only means, and, as such, we are ontologically subject to the ends.7

Mass porn is just one of the myriad of technological objects, products, and services that form our modern world. As such, porn is subject to the same dynamics as any other product, including a possible addictive quality that compels consumers to spend more and more time surfing on porn websites, looking for the ultimate fragment of an unfulfillable desire.

The English word addiction comes from Latin addictus, which meant “delivered as a slave to someone”. The common expression used in Italian is dipendenza, which condensates in one word “addiction, dependence, dependency, reliance”. As human beings, we definitely depend on our technological world in manifold ways: our physical sustenance, our health care, our learning and socialisation processes, and ultimately our survival currently rely, to some extent, or even totally, on the “system of apparatuses”, as Anders calls it.

Moreover, our current mater-ialistic society embodies the mater-nal function, that of a mother (indeed mater in Latin), in a distorted way, as it transforms us into dependent, permanent children, by nourishing our needs, creating new ones, and fulfilling them, but never enough, in order to perpetuate itself.

From dependency to addiction is not a very long step. Allegedly, it’s just a matter of degree on a continuum. At any rate, the technological apparatus tends towards addictions, as they represent the absolute state that would ensure its expansion and its duration.8

There is no doubt that more and more people are running serious risk of developing an addiction (in the etymological sense, as we mentioned, of being slave) to porn images, compelling them to spend an increasing amount of their time surfing on the net, and manifesting in withdrawal symptoms. Presumably, researchers would find very similar results were they to explore the use and the common abuse of smart phones, of social networks, of video games, of websites, and so on.

Dependency/addiction is de facto the current condition in which we are immersed, and where this is not yet so, it is subtly cultivated, encouraged, and even praised.

Although we may reasonably make every effort to get rid of the most severe forms of addiction, including that to porn, this seems to me like trying to turn off an electric fan in the middle of a windstorm. As a matter of fact, there has never been in the whole of human history such a deployment of forces and means aimed at teaching us to need, to depend on, and to be addicted to what is offered, in every area of our lives.

CHAPTER TWO

Porn and phantoms

Whether in static or moving pictures, porn always presents a defiant, provocative image. Seductive, repulsive, fascinating, appalling—a porn image instantly arouses a powerful emotional response in the viewer, no m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Introduction

- Chapter One Porn and technology

- Chapter Two Porn and phantoms

- Chapter Three Porn and seduction

- Chapter Four Porn and the roses of Kenya

- Chapter Five Porn and no limit

- Chapter Six Porn and shadow

- Chapter Seven Porn and as if

- Chapter Eight Porn and divinity

- Chapter Nine Porn and lost goddesses

- Notes

- References

- Appendix The quest for meaning after the end of meaning

- Index