eBook - ePub

Psychoanalytic Couple Therapy

Foundations of Theory and Practice

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Psychoanalytic Couple Therapy

Foundations of Theory and Practice

About this book

In this time of vulnerable marriages and partnerships, many couples seek help for their relationships. Psychoanalytic couple therapy is a growing application of psychoanalysis for which training is not usually offered in most psychoanalytic and analytic psychotherapy programs. This book is both an advanced text for therapists and a primer for new students of couple psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Its twenty-eight chapters cover the major ideas underlying the application of psychoanalysis to couple therapy, many clinical illustrations of cases and problems in various dimensions of the work. The international group of authors comes from the International Psychotherapy Institute based in Washington, DC, and the Tavistock Centre for Couple Relationships (TCCR) in London. The result is a richly international perspective that nonetheless has theoretical and clinical coherence because of the shared vision of the authors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Psychoanalytic Couple Therapy by David E. Scharff, Jill Savege Scharff, David E. Scharff,Jill Savege Scharff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES OF PSYCHOANALYTIC COUPLE THERAPY

CHAPTER ONE

An overview of psychodynamic couple therapy

Psychodynamic couple therapy is an application of psychoanalytic theory. It draws on the psychotherapist’s experience of dealing with relationships in individual, group, and family therapy. Psychodynamic couple therapists relate in depth and get firsthand exposure to couples’ defences and anxieties, which they interpret to foster change. The most complete version of psychodynamic therapy is object relations couple therapy based on the use of transference and countertransference as central guidance mechanisms. Then the couple therapist is interpreting on the basis of emotional connection and not from a purely intellectual stance. Object relations couple therapy enables psychodynamic therapists to join with couples at the level of resonating unconscious processes to provide emotional holding and containment, with which the couple identifies. In this way they enhance the therapeutic potential of the couple. From inside shared experience, the object relations couple therapist interprets anxiety that has previously overwhelmed the couple, and so unblocks partners’ capacity for generative coupling.

The development of couple therapy

Couple therapy developed predominantly from psychoanalysis in Great Britain and from family systems theory in the United States. At first the limitations of classical psychoanalytic theory and technique inhibited psychoanalysts from thinking about a couple as a treatment unit. In reaction to that inadequacy for dealing with more than one person at a time, family systems research developed. However, many of the early systems theorists were also analytically trained or had been analysed, and so psychoanalysis had an influence on systems theory contributions to family therapy, and its extension to couple therapy in the United States (J. Scharff & D. Scharff, 2003). With wider access to object relations theory from psychoanalysis in Great Britain an enriched form of psychoanalysis readily applicable to couples emerged.

Until then, psychoanalytic theory had stressed the innate drives of sexuality and aggression (Freud, 1905). Freud made little reference to the effect of the actual behaviours of parents on children’s development, unless abuse had occurred (Breuer & Freud, 1893–1895). True, Freud’s later structural theory dealt with the role of identification with selected aspects of each parent in psychic structure formation, but these identifications were seen as resulting from the child’s fantasy of family romance and aggression towards the rival, not from the parents’ characters and parenting styles (Freud, 1923). It was as though children normally grow up uninfluenced by those they depend on until the Oedipus complex develops. Even then, the psychoanalytic focus was squarely on the inner life of the individual.

In the United States, family systems theorists understood that spouses became part of an interpersonal system, and then devised ways of changing the system. However, without an understanding of unconscious influence on behaviour they could not address the irrational forces driving that system. In addition, they remained more interested in family systems than in couple systems for many years.

In Great Britain

Object relations theory emerging in Great Britain was also an individual psychology, but since it was being developed to address the vicissitudes of the analyst-analysand relationship, it lent itself well to thinking about couples, as shown by Enid Balint and her colleagues and students at the Family Discussion Bureau of the Tavistock Centre. As object relations theory continued to develop in Great Britain, it provided the theoretical foundation needed for the psychodynamic exploration of marital dynamics being explored at the Tavistock in what was now called the Tavistock Institute of Marital Studies in the 1950s (Pincus, 1955). Then in 1957, it was the publication of Henry Dicks’s (1967) landmark text, Marital Tensions, integrating Fairbairn’s theory of endopsychic structure and Klein’s concept of projective identification that gave the crucial boost to the development of a clinically useful couple therapy. At that time, two therapists in the Adult Department of the Tavistock Clinic treated a married couple by one of them treating the husband while the other treated the wife, and then reported on their sessions at a shared meeting with a consultant. The team could then see how the individual psychic structures of marital partners affect one another. This observation led Dicks to realise that the psychic structures interact at conscious and unconscious levels through the central mechanism of projective identification to form a “joint marital personality,” different from, and greater than, the personality of either spouse. In this way, partners rediscover lost aspects of themselves through the relationship with the other. Later, Dicks and his colleagues realised that it was more efficient for a single therapist to experience the couple’s interaction first-hand, and couple therapy as we know it today had arrived (Dicks, personal communication).

In America

The next boost to couple therapy came from psychoanalysis in South America where modern concepts of transference and countertransference were being analysed in detail. Racker (1968) thought that countertransference was the analyst’s unconscious reception of a transference communication from the patient through projective identification. He said that this counter-transference might be of two types, concordant or complementary. The concordant identification is one in which the analyst resonates with a part of the patient’s ego or object. The complementary identification is one in which the analyst resonates with a part of the patient’s object. Let’s say that the patient who was abused by his father feels easily humiliated by aggressive men in authority positions. He feels like a worm in front of the analyst whom he glorifies, and he defends against this feeling of weakness and insignificance by boasting about his income. If the analyst feels envious and impoverished in comparison, he is identifying with the patient’s ego (concordant identification). If the analyst responds by puncturing the boastful claims, he is identifying with the patient’s object derived from his experience with his father (complementary identification). After Racker, analysts could understand their shifting countertransference responses as a reflection not just of the transference, but of the specific ego or object pole of the internal object relationship.

This insight from psychoanalysis deepened appreciation for the way that a relationship is constructed, each partner to the relationship resonating with aspects of projective identifications to a greater or lesser degree. Applying this insight to the couple relationship between intimate partners, couple therapists could better understand how partners treated one another. They also had a way of using their unique responses to each couple to understand how the partners connected with their therapist.

In North America in the 1960s, Zinner and Shapiro (1972) went against the systems theory mainstream to study the family systems of troubled adolescents in relation to their individual psychic structures, using Dicks’s ideas as the explanatory linking concept. Focusing on the parents as a couple Zinner (1976) extended Dicks’s ideas on marital interaction to explore marital issues as a source of disruption to adolescent development. Their research findings provided further support for the value of couple therapy. Another boost came in the 1970s from developments in the understanding and treatment of sexuality (Masters & Johnson, 1970; Kaplan, 1974; D. Scharff, 1982). Object relations theory of couple therapy now included an object relations approach to sexual intimacy (J. Scharff & D. Scharff, 1991). Furthermore, in the 1990s, research on attachment processes stemming from the pioneering work of Bowlby, revealed that early infant attachment bonds influence the attachment patterns of adults, which has a profound effect on the life of couples and on the attachment styles of their children. Several clinicians and researchers have applied infant and adult attachment concepts to study the complex attachment of couples (Clulow, 2000; Bartholomew, Henderson, & Dutton, 2000; Fisher & Crandall, 2000).

Theoretical basis of psychodynamic couple therapy

Fairbairn’s model of psychic structure

Fairbairn held that the individual is organised by the fundamental need for relationships throughout life. The infant seeks a relationship with the mother (or primary caretakers) but inevitably meets with some disappointment, for example, when the mother cannot be available at all times or when the infant’s distress is too great to be managed. The mother who is beckoning without being overly seductive, and who can set limits without being persecuting or overly rejecting infuses the infant’s self with feelings of safety, plenty, love, and satisfaction. The mother who is tantalising, overfeeding, anxiously hovering, excessively care taking, or sexually seductive is exciting but overwhelming to the infant, who then feels anxious, needy, and longing for relief. The mother who is too depressed, exhausted, and angry to respond to her infant’s needs has an infant who feels rejected, angry, and abandoned. The mother who gets it more or less right, has an infant who feels relaxed, satisfied and loved.

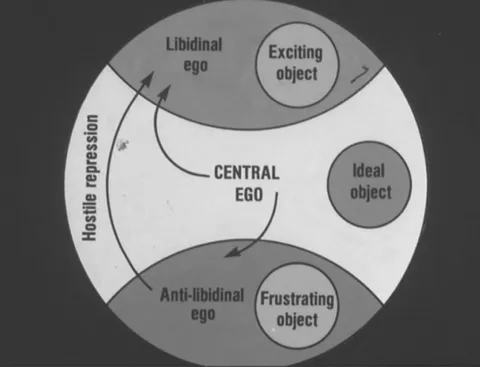

When a frustrating experience occurs, the infant takes into the mind, or introjects, the image of the mother as a somewhat unsatisfying internal object, whether of an exciting or rejecting sort. The infant’s next response is to split off the unbearably unsatisfying aspects from the core of this rejecting internal object and repress them because they are too painful to be kept in consciousness. However, whenever a part of an object is split and repressed, a part of the ego or self that relates to it is also split off from the main core of the ego along with the object. This now repressed relationship between part of the ego and an internal object is characterised by an affect. The rejecting object is connected to affects of sadness and anger. The exciting object is connected to affects of longing and craving. Remaining in consciousness connected to the central ego is the ideal object characterised by affects of satisfaction.

Figure 1. Fairbairn’s model of psychic organisation. The central ego in relation to the ideal object is in conscious interaction with the caretaker. The central ego represses the split-off libidinal and anti-libidinal aspects of its experience along with corresponding parts of the ego and relevant affects that remain unconscious. The libidinal system is further repressed by the anti-libidinal system when anger predominates over longing as shown here, but the situation can reverse so that the libidinal system can act to further repress the anti-libidinal system when an excess of clinging serves to cover anger and rejection. (Copyright David E. Scharff reproduced courtesy of Jason Aronson.)

This produces three tiers of three-part structures in the self: central, rejecting and exciting internal object relationships in the ego, and within each internal object relationship, a part of the ego, the object, and the affect that binds them.

In health, these elements of object relations organisation are in internal dynamic flux, but in pathologically limited states, one or another element takes over at the expense of others in a relatively fixed way. So one person can be frozen into an angry rejecting stance towards others if dominated by rejecting object qualities; another can be fixed in an excited, seductive, and sexualised way of relating. In some trigger situations, one of these ordinarily buried ways of relating can take over in an automatic and repetitious way.

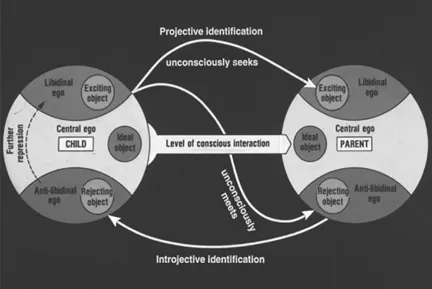

Klein and Bion’s theory of projective and introjective identification

Klein proposed that people relate unconsciously and wordlessly by putting parts of themselves that feel dangerous or endangered into another person by projection. This unconscious mechanism characterises all intimate relationships beginning with the infant–parent relationship and continuing throughout life. Through facial gesture, vocal inflection, expressions of the eyes, and minute changes in body posture each of us continuously communicates subtle unconscious affective messages even while communicating a different message consciously, rationally, verbally. These affective messages are communicated from the right frontal lobe of the brain of one person to the right brain of another below the level of consciousness, but they fundamentally colour the reception of all communications (Schore, 2001). They transmit parts of oneself to the interior of the other person where they resonate with the recipient’s unconscious organisation (a projective identification) and may evoke identification with the qualities of the projector. The recipient of a projective identification takes in aspects of the other person through introjective identification.

For instance, a child who fears his own anger will place it in his mother, identify her with his own anger, and then feel as afraid of her as he felt of his own temper. Or a weak wife who longs for strength, but also fears it, chooses a tyrannical husband whose power she regards with a mixture of fear and awe. A husband who is afraid that being sympathetic implies weakness locates tenderness in his wife or children, where he both demeans it and treasures it.

Bion (1967) described the continuous cycle of projective and introjective identification that occurs mutually between mother and infant. He studied the maternal process of containment, in which the parent’s mind receives the unstructured anxieties of the child where they unconsciously resonate with the parent’s mental structure, and the parent then feeds back more structured, detoxified understanding that in turn structures the child’s mind. In this way, the child’s growing mind is a product of affective and cognitive interaction with the parents. The same thing happens in couples: continuous feedback through cycles of projective and introjective identification is the mechanism for normal unconscious communication that is the basis for deep primary relationships. Bion (1961) also described valency, the spontaneous emotional clicking of strangers in a group setting, governed by fit between their unconscious needs. A couple is a special, small group of two who click as strangers and choose to become intimate, based on their unconscious needs.

Dicks

Dicks (1967) built his theory of marriage by integrating these elements from Fairbairn and Klein (to which we later added the contributions from Bion on valency and containment). Marriage is a state of continuous mutual projective identification. Interactions of couples can be understood both in terms of the conscious needs of each partner and in terms of shared unconscious assumptions and working agreements. Cultural elements are the most obvious determinants of marital choice—the sharing of backgrounds or values that are part of conscious mate selection-but Dicks’s research showed that the long-term quality of a marriage is primarily determined by an unconscious fit between the internal object relations sets of each partner.

Figure 2. Projective and introjective identification in a marriage.

Let’s read this diagram of a couple relationship from the husband’s point of view. A husband craves affection from an attractive but busy wife. He hopes she will long for him as he longs for her, but she is preoccupied and pushes him away. He responds by rejecting her before she can reject him and he squashes his feelings of love for her. To put this in technical terms, his exciting object relationship seeks to return from repression by projective identification with his wife’s exciting object relationship. Instead, it is further repressed by her rejecting object relationship with which he identifies in self-defence. His rejecting object ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- About the Editors and Contributors

- Series Editor’s Foreword

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Part I: Fundamental Principles of Psychoanalytic Couple Therapy

- Part II: Assessment and Treatment

- Part III: Understanding and Treating Sexual Issues

- Part IV: Special Topics

- Epilogue

- Index