eBook - ePub

Phantoms of the Clinic

From Thought-Transference to Projective Identification

- 158 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As Freud predicted, there has always been great anxiety about the place of psychoanalysis in contemporary life, particularly in relation to its ambiguous and complicated relationship to the realm of science. There is also a long history of widespread resistance, in both academia and medicine, to anything associated with the world of the supernatural; very few people, in their professional lives, at least, are willing to admit a serious interest in occult phenomena. As a result, paranormal traces have all but vanished from the psychoanalytic process - though not without leaving a residue. This residue remains, the author argues, in the acceptably "clinical" guise of projective identification, a concept first formulated by Melanie Klein, and widely used in contemporary psychoanalysis to suggest a different variety of transference and transference-like phenomena between patient and analyst that seem to occur outside the normal range of the sensory process.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Phantoms of the Clinic by Mikita Brottman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Psychoanalysis and magic

“ ... if I had to live my life over again, I should devote myself to psychical research, rather than psychoanalysis ...”

(Freud, letter to Hereward Carrington, 1921, quoted in Jones, 1957)

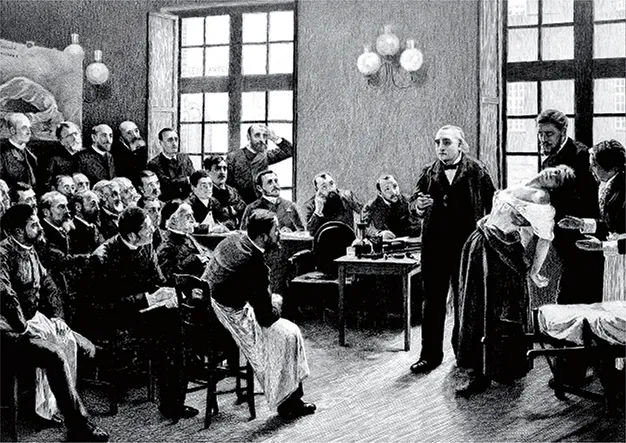

Freud is often accused of secularizing the transcendental by suggesting that psychic material is simply the projection of mental content into the physical world. This, however, is a mischaracterization of Freud’s depiction of psychic reality, which he believed to be just as real as the material world, and capable of manipulating and infecting it in various fascinating ways. In this, he was influenced, like other seminal thinkers of the day, by the rapid spread of spiritualism in Europe and America in the 1850s and 1860s. Spiritualism, in its turn, quickly led to the rise of rationalist circles devoted to exploring the unexplained phenomena apparently produced by trances and séances. In Britain, one of these circles became the Society for Psychical Research, which was established in 1882 when a number of spiritualists and Cambridge scholars grew determined to place their belief in psychic phenomena upon a sound, unprejudiced footing grounded in the scientific method. A new model of the unconscious mind emerged in the many publications of this society’s members (see Koutstaal, 1992; Noll, 1997; Shamdasani, 1993), who considered such phenomena as trance states, crystal gazing, and automatic writing to be perfectly valid psychological methods for studying what they referred to as the “ subliminal self”. Indeed, authors Léon Chertok and Raymond de Saussure, in their 1979 book The Therapeutic Revolution, draw a connection between the Victorian obsession with psychic phenomena and the “new science” of psychoanalysis—in particular, the Freudian concept of transference. The connection, according to Chertok and de Saussure, goes back to August 1885, when Freud first began studying hypnotism under the auspices of Jean-Martin Charcot at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris. Freud’s interest in the subject reflected the widespread public fascination with mysterious states of mind, including somnambulism, magnetism, catalepsy, nervous illness, and the fragmentation of personality. His later speculations about the unconscious mind were deeply influenced by the work of Charcot, especially his use of hypnosis to relieve the various automatic phenomena induced by hysteria.

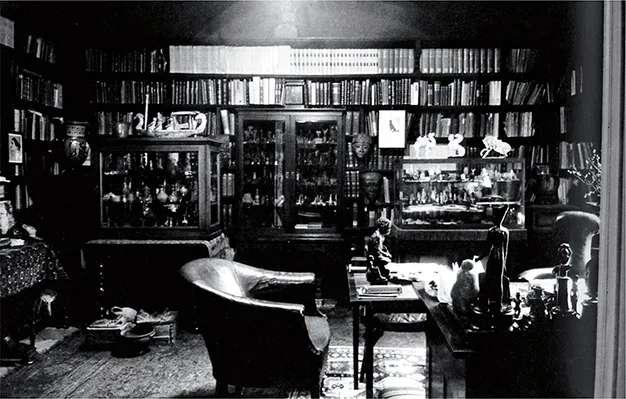

Illustration 1.1. Freud’s study in Vienna. © Edmund Engleman, 1938.

As the psychoanalytic movement slowly gained prominence, the earlier work of mesmerists and spiritualists on the “subliminal self” was overshadowed and largely forgotten—though certainly not by Freud, who never lost his fascination with unconscious (but active) ideas, and, at least in his younger days, readily acknowledged the connections between psychoanalysis and magic. The following passage, from his essay “Psychical (or mental) treatment” (written when he was thirty-four), provides a neat summary of his position at this time:

Illustration 1.2. “A Clinical Lesson with Dr Charcot at the Salpètrière”, by Pierre André Brouillet (1887), the print that hung above Freud’s couch.

A layman will no doubt find it hard to understand how pathological disorders of the body and mind can be eliminated by “mere” words. He will feel that he is being asked to believe in magic. And he will not be so very wrong, for the words which we use in our everyday speech are nothing other than watered down magic. But we shall have to follow a roundabout path in order to explain how science sets about restoring to words at least a part of their former magical power. [1890a, p. 285]

Obviously, Freud was well aware of the connections between words and magic, and the capacity of words to engage and reflect primitive ways of thinking. “When the riddle [that neurosis] presents is solved and the solution is accepted by the patients, these diseases cease to be able to exist”, he observed. “There is hardly anything like this in medicine, though in fairy tales you hear of evil spirits whose power is broken as soon as you can tell them their name, the name which they have kept secret” (1910e, p. 148).

Language has always been intimately connected with magic, not least in the capacity of words to evoke deep and powerful emotions. This is the kind of magic that emerges on the couch—the magic of words, the “talking cure”. With its collection of fetishes, idols, and exotic fabrics, Freud’s consulting room was particularly appropriate for the summoning of magic. Indeed, Freud remarks in Totem and Taboo that the “ceremonial” element in psychoanalytic practice represents a “remnant of the hypnotic method out of which psycho-analysis was evolved” (1912-1913, p. 133). Quite clearly, anyone who expresses a belief in magic lays him or herself open to accusations of credulity, but Freud was careful to emphasize that he was not in the least bit superstitious. In The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901b), he wrote, “I believe in external (real) chance, it is true, but not in internal (psychical) accidental events. With superstitious persons it is the other way round” (p. 257).

From mesmerist to medic

By 1918, Freud was no longer writing full-blown case studies, and his work, though interesting in other ways, never resumed the intriguing, mysterious tone it achieves in his earlier works such as Studies in Hysteria (1895d), where he and Breuer seem more like alchemists or Svengalis than a pair of respectable physicians. According to Swales (1986), in his essay on the early years of psychoanalysis, Freud was known as der Zauberer (“the Magician”) by the children of Anna von Lieben, a rich patient whom he treated at home in the 1880s. Not quite a “proper doctor”, he was, Swales informs us, generally received at the back door of his patients’ homes, rather than the front. It does not seem surprising, then, that in his early work, Freud cast himself as a magician of the word. At the beginning of his career, in fact, Freud considered himself ill suited to medicine. “As a young man, I knew no longing other than for philosophical knowledge”, he wrote to Wilhelm Fliess in 1896. “I became a therapist against my will” (1985, p. 180). Thirty years later, at the age of seventy, he returned to the same theme. “After forty-one years of medical activity, my self-knowledge tells me that I have never been a doctor in the proper sense”, he wrote. “I became a doctor through being compelled to deviate from my original purpose; and the triumph of my life lies in my having, after a long and roundabout journey, found my way back to my earliest path” (1926e, p. 253).

At the beginning of his career, Freud believed he could merge his interests in thought-transference, telepathy, and precognition with his “new science” of psychoanalysis. During this period, however, the field of psychiatry was rapidly disentangling itself from the realm of the spiritual. Freud became concerned that if people began to associate psychoanalysis with the occult and supernatural, his new discipline—already controversial for its insistence on childhood sexuality—would be gravely endangered. His doubts were encouraged by his colleague Ernest Jones, who, openly embarrassed by Freud’s interest in the occult, urged him to forge closer affiliations between his “new science” and that of medicine—affiliations which, Jones felt, would considerably enhance the prestige of psychoanalysis. Jones worked hard to convince Freud that he was risking the reputation of their profession—and insulting their status as physicians—by continuing to dabble in the occult. Before long, Freud was persuaded. “We are physicians, and wish to remain physicians”, he told Otto Gross at the 1908 Salzburg psychoanalytic conference when Gross spoke on “the cultural perspectives of science” (cited in Schwentker, 1987, p. 488). Not long after this, however, psychoanalytic authors began publishing articles on European culture as a whole, its myths, fairy tales, literature, opera, and so on, attracting the attention of many readers and thinkers in fields far beyond that of science.

Still, Freud remained anxious that his ideas about thought-transference might be misunderstood, and possibly appropriated by spiritualists and mystics eager to prove the universe contains more than mere material forms. Consequently, during the writing of Totem and Taboo, he clashed famously with his close friend and colleague C. G. Jung, struggling to resist the seductive mysticism of the other man’s work. When Totem and Taboo was finally published in 1913, Jung was dismayed to discover that Freud came down stoutly in favour of a material, mechanistic theory of scientific rationalism. In his autobiographical work Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1965), Jung observed that Freud’s fear of the occult sometimes verged on the histrionic (p. 84), and it does not seem outlandish to speculate that, for Freud, supernatural manifestations resonated with a particular significance. In defence, Freud began to rationalize spiritual belief as a form of primitive thinking typical of children and psychotics, which in Totem and Taboo he refers to as “animism”. According to Freud, “primitive races . . . people the world with innumerable spiritual beings both benevolent and malignant; and these spirits and demons they regard as the causes of natural phenomena ...” (p. 76).

Nevertheless, as his career took shape, Freud often expressed regret that he had not devoted himself more seriously to paranormal investigation. Jones, in his 1953-1957 biography, quotes a reflective letter Freud wrote in 1921, at the age of sixty-five, to the British spiritualist, author, magician and psychic researcher, Hereward Carrington. In this letter, Freud confesses that, “if I had to live my life over again, I should devote myself to psychical research, rather than psychoanalysis” (p. 392). The subject must have pressed heavily on his mind; that same year, he received offers to become the co-editor of three periodicals devoted to occultism. His decision to turn down these offers had nothing to do with his feelings about the occult, and everything to do with the politics of psychoanalysis. As his work had become increasingly well respected, he had finally realized that the two fields of study— psychoanalysis and psychic research—were mutually exclusive.

In public, then, Freud worked hard to keep the boundaries of psychoanalysis distinct from those of the occult. In private, however, as Ernest Jones describes in his biography, Freud displayed “an exquisite oscillation between skepticism and credulity” (1957, p. 375) on the subject. It is interesting to note that even Jones, Freud’s staunchest supporter, was privately sarcastic about his mentor’s occult interests. To Jones’ dismay, however, not only did Freud express constant anxiety about the assimilation of psychoanalysis into the realm of science, he also continued to claim that the occult was inextricable from psychoanalysis, which, he believed, in order to be effective, had to embrace those manifestations of thought and emotion that are normally excluded from rational, scientific study. And while he remained ambivalent and conflicted about the more other-worldly reaches of occult belief, he always considered thought-transference to be the most respectable element in occultism, and the main “kernel of truth in the field” (1922a, p. 136). In fact, he believed the phenomenon would soon be incorporated into the realm of scientific fact. In an article entitled “A note on the unconscious in psycho-analysis”, published in the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research (1912g), he wrote that, as far as he was concerned, future evidence from analysts would soon “put an end to any remaining doubts on the reality of thought-transference” (p. 266).

Freud was supported and encouraged in his occult investigations by his Hungarian colleague, Sandor Ferenczi, who had long been fascinated by the subject of thought-transference, and, as early as 1899, had published a paper—entitled simply “Spiritism”—in which he explained his conviction that the unconscious was an occult phenomenon that allowed access into the minds of others. Eventually, Ferenczi went so far as to actively erase the rigid frontier Freud had carefully traced between the “alloy” of suggestion and the “pure gold” of psychoanalytic practice. Consequently, as Freud heeded Jones’ advice and ceased to speak and publish openly on the paranormal, Ferenczi was cast out of the “inner circle” and his work—like Freud’s own publications on the occult—became something of an embarrassment to mainstream psychoanalysis.

In his anthology Psychoanalysis and the Occult (1952), Devereux refers to 235 papers on telepathic experiences in psychoanalysis, of which he reprints thirty-one, including essays by Jule Eisenbud, Jan Ehrenwald, Nandor Fodor, and other notable scholar-practitioners. By the 1970s, however, at least in orthodox psychoanalysis, the subject had virtually disappeared from view. Today, psychoanalytic thinkers with an interest in such topics generally gravitate toward the field of transpersonal psychology, where paranormal experiences are generally believed to provide meaningful moments in the process of life. Some interest in thought-transference, unconscious communication, and even the paranormal continues to hover around current work on Ferenczi and Freud’s papers on telepathy, however, as well as in, more generally, the work of such figures as the late psychology professor Elizabeth Lloyd Mayer. While the place of these subjects within mainstream psychoanalytic thought remains ambiguous, I want to suggest that magical thinking has always been the motor driving psychoanalytic practice—an opinion with which many in the field would, I suspect, readily disagree.

The secret laws of magic

As Bernstein (2002) reminds us, the word “magic” originally meant “of the magi”—the wise men of the Persians reputed to be skilled in enchantment. Definitions of magic include “any mysterious and overpowering quality that produces unaccountable or baffling effects”, “the gratification of desires otherwise unobtainable”, and “that which takes us beyond the ordinary action of cause and effect which we regard as natural” (p. 235). With these definitions in mind, it seems clear that psychoanalysis is full of magical elements, especially in relation to the vicissitudes of the transference. The analytic encounter, with its deliberate quiet, low lighting and use of the couch as a liminal space, specifically encourages the evocation of magic. Although Freud grew increasingly wary about the place of magic in psychoanalysis, plenty of magical elements remain in his theory and clinical practice. As Whitebook argues (2002), the ambition to completely exorcise “enchantment” from human experience was one of the more misguided excesses of the Enlightenment (p. 1197).

In Totem and Taboo, Freud explains how the logic of magical practices reflects the pattern of ideas underlying such practices, which is similar to the patterns of dreams and neurotic symptoms—that is, the logic of the unconscious: the primary process. “The world of magic”, he writes, “has a telepathic disregard for spatial distance and treats past situations as though they were present” (p. 85). “Magic reveals in the clearest and most unmistakable way an intention to impose the laws governing mental life upon real things” (p. 91), and, thereby, “replace the laws of nature with psychological ones” (p. 83). These psychological laws, however, are primitive and infantile, dominated by the governance of the pleasure principle:

It is easy to perceive the motives that lead men to practise magic: they are human wishes. All we need to suppose is that primitive man had an immense belief in the power of his wishes. The basic reason why what he sets about by magical means comes to pass is, after all, simply that he wills it. To begin with, therefore, the emphasis is only upon his wish. Children are in an analogous psychical situation. [1912-1913, p. 83]

It would be wrong to assume that, in our “civilized” adult lives, magic no longer plays a part. On the contrary, the “infantile” magical orientation generally continues into later life relatively unmodified, existing side by side with more highly developed rational and “scientific” cognitive processes. Recent research suggests that otherwise reasonable people often act as though they believe they possess magical powers (though they may consciously deny it), a phenomenon which may be traceable to basic cognitive errors involving the perception of causal relationships. This kind of magical thinking occurs particularly in times of uncertainty or stress, and serves our need for control, especially our need to perceive ourselves as able to navigate a clear path through uncontrollable situations. Support for this explanation comes from studies showing that people display signs of magical thinking when they are faced with a combination of uncertainty about an outcome and a desire for control over that outcome (Bleak & Frederick, 1998; Friedland, Keinan, & Regev, 1992; Keinan, 1994; Matute, 1994). Magical thinking has been closely documented among Germans at the period of high unemployment and political instability in between the wars (Padgett & Jorgensen, 1982); police officers with jobs that put them in dangerous situations (Corrigan, Pattison, & Lester, 1980); HIV-infected men with no agency over their health (Taylor, Kemeny, Reed, Bower, & Gruenewald, 2000), and lottery players who possess illusions of control regarding their ability to influence chance gambles (Langer, 1975). In most cases, this magical thinking is opaque to those engaged in it. Even when people recognize that control over life events may be impossible to achieve, magical beliefs may arise out of a motivation to find “meaning” in that which they cannot control (Pepitone & Saffiotti, 1997). It is well known, too, that magical thinking can sometimes have equally magical results. Patients with metastasized cancer mysteriously may go into remission and make miraculous recoveries. Experiments with placebos show that, in some circumstances, people have the power within them to produce all the effects of drugs, both benefits and side effects.

Freud always insisted that occult phenomena obeyed the same principles that underlie the psychodynamics of dreams, neurotic symptoms, and primary process thinking in general: the absence of “adult”, ego-generated logic and order, and a lack of attention to such details as time and money. Clearly, these hallmarks of adult reality have no place in the magical world of the unconscious. As Freud acknowledged in his work on dreams, primary process thinking is timeless. In our dreams, split seconds last for eternities, years pass in seconds, and chronologies are scrambled or reversed. This is the realm of myth, fairytales, and folklore, in which everyone is immortal. As Bergler and Roheim (1946) put it,

[t]ime perception is an artefact built in the unconscious ego after the partial mastering of blows against the ‘autarchic fiction’...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Psychoanalysis and magic

- Chapter Two: A brief history of thought-transference

- Chapter Three: Residues of the uncanny

- Chapter Four: Mothers and other ghosts

- Chapter Five: What is projective identification?

- Chapter Six: Afterword

- References

- Index