![]()

1

From Action to Representation: The Origins of Early Graphic Forms

The first drawings of a child that evoke a smile of recognition usually take us by surprise. Figures appear quite abruptly, born as it were out of scribble chaos, and we wonder how the preschooler has acquired the unsuspected ability to create a meaningful figure. Our curiosity aroused, we search for the origins and antecedents of pictorial representation.

We might begin our exploration of child art by taking a look at the earliest marks toddlers make and ask whether the traces left in mud, sand, or paper are the first steps on the road to pictorial representation and herald the onset of children’s drawings. In our search for the origins of early graphic forms, we shall focus on two different sets of assumptions about the antecedents of representational drawing. One position asserts that refinements of motor movements and elaborations of scribble shapes will eventually lead to the drawing of recognizable forms. An alternative view identifies specific points of transition at which scribble actions are transformed into symbolic actions that yield meaningful figures.

A review of the literature indicates that most students of children’s art have not attributed much significance to the early scribble ventures. The toddler’s scribbles have been identified as a motor activity that is largely devoid of visual guidance and that elicits in the child only a fleeting interest in the product of his actions (Burt, 1921; Goodenough, 1926; Luquet, 1913, 1927; Munro, Lark-Horowitz, & Barnhard, 1942; Piaget & Inhelder, 1956). From this perspective the scribble pictures appear as unintentional and unanticipated visual records of movements, largely determined by the mechanical structure of the arm, the wrist, and the hand. To the extent that the hand with pencil or crayon acts independently of the eye, the incidental marks that ensue from the gestures do not carry graphic meaning. Whether or not the scribble picture evolves accidentally, once it is made the child is quite proud of having left a mark where none was before. Although initially awareness and planning may have been absent, with their scribble marks the children have created an “existence,” they have left 8 a record of their actions and made a statement of “having been there.” Despite children’s evident pleasure in making marks, their early scribble productions have received only scant attention since neither children nor adults can easily decode their message or attribute meaning to the scribble pictures. This state of benign neglect is beginning to be rectified, and recent years have seen several attempts to analyze the scribbles as potentially useful graphic elements destined, perhaps, to play a role in later development (Haas, 1984, 1998, 2003; Kellogg, 1969; Matthews, 1984; Smith, 1972). Let us examine more closely the views of two authors, John Matthews and Rhoda Kellogg.

Antecedents: Mark-Making and Scribble Ventures

John Matthews (1984, 1999) bases his account of the earliest phases of graphic development on carefully documented longitudinal observation of his three children. He alerts us to the often-forgotten fact that long before they discover paper and pencil, infants and toddlers leave many traces of their gestures. With an attentive and caring eye, he reports on the visual-motor explorations of his six-month-old infant, whose glance is caught by a patch of regurgitated milk on the carpet. The baby first reaches for the puddle and then modifies his reach as he scratches the puddle, an action that changes the substance markedly. Undisturbed by the milky invasion of the carpet, Matthews describes this process as a first instance of “mark-making.” He lists three basic mark-making movements that he considers essential to later drawing activity. The first is a downward stabbing motion of arm and hand that collides with its object at a near-right angle. This movement he calls the “vertical arc.” The second is a sweeping or swiping motion directed at a horizontal surface; it encounters its object as it sweeps across the floor, the table, or the tray of the baby’s high chair. This motion, well-suited to smearing and painting, is called the “horizontal arc”; it yields knowledge of the body space that surrounds the infant. The third motion to qualify as a basic mark-maker is called the “push-pull” action. The toddler grips a pen or a marker, pushes it as far as the arm can reach, and then reverses the direction and returns to the starting point. This action creates a line that travels the length of the paper away from the child, and back toward him. Push-pull actions consist of a series of forward and return motions. Unlike the child’s ordinary push-pull actions that displace real objects but do not leave a visible trace of its movement, the pen creates a distinctive visual mark. These three types of body action performed with marker or brush leave, in Matthews’ phrase, “a trace of their passage through space and time.”

Beginning with the second year of life, the Matthews children—all of whom are fortunate to have access to their father’s studio—explore and handle brushes and paints and discover the effects their vertical stabs and horizontal swipes can have on various surfaces. The photographs of these activities show infants interested in their actions and in the marks they leave. The running commentaries of the sensitive adult observer inform us that the hand adapts to different kinds of reaches. For example, the handle of the brush can be grasped in a palmar or a pincer grip; that is, the palm of the hand can enclose the handle or two fingers can grip its endpoint. Just as the hand can adjust to the tool held, so the child’s posture adapts to the action. We see the toddler crouching while he swings the paint-dipped brush in a semicircular arc and splatters the paint by centrifugal force; we see him standing when he makes vigorous up–down gestures in space and thus disperses the paint droplets by inertial force. At this time, markings are not yet limited to floor and paper surfaces, but are also made on the child’s own person. These varied explorations with paint and brush reveal to the child his normally invisible movements in space. Thus, the temporal sequence of ongoing activities is given visible shape in a manner that calls attention to itself. The child’s body serves as the center from which these actions in space ensue, with the horizontal arc describing a continuous motion around the body’s vertical midline, the push–pull action following a linear axis to and from the self, and the vertical arc aiming at discrete targets. Although these three mark-making actions are merely recorded gestures—and one might add bang-dots to this repertoire of actions (Smith, 1972, 1983)—Matthews suggests that these gestures underlie all later drawing activity and play a role in establishing a spatial signifying system.

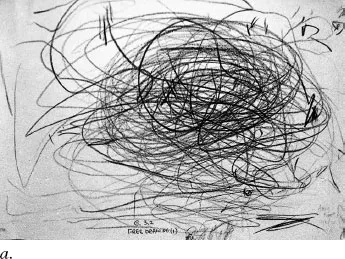

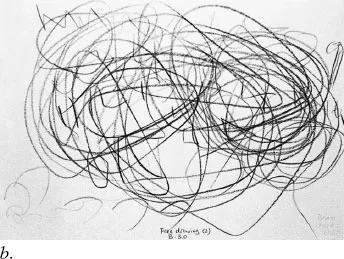

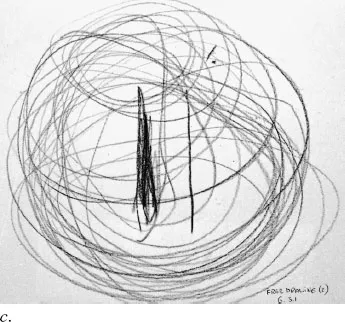

1. Scribble Whirls

a. Girl, 3;2.

b. Boy, 3;0.

c. Girl, 3;1.

From the middle of the second year we can see further explorations as new combinations are tried out and a newly won control over the motor action facilitates the separation of formerly continuous motions. For example, pull lines can now be separated from push lines, and horizontal arc sweeps can combine with pull lines to yield the familiar continuous rotations best known as scribble whirls (see ills. 1 a, b, c). These newly combined action patterns also yield interesting right-angular structures, the outcome of an active visual attention to the marker, the movement, and the mark. The author’s illustrations show a young two-year-old absorbed in his own mark-making actions. To the extent that these line configurations manage to stay within the frame of the paper surface, the notion that these actions demonstrate some degree of visual guidance is quite plausible; other observers have noted the child’s search for “empty spaces” in which to place their marks (P. Tarr, April 19, 1987, Tarr, 1990), and Malka Haas (1998) has called attention to what appear to be individual differences. She documents how some young two-year-olds, in their focused attention to the emerging lines, show an early visual-spatial orientation to the marks and their spatial surround, carefully staying within the paper’s boundaries. Such control, however, is not always the case. Other examples of two-year-old youngsters indicate that despite daily scribble experiences, the lines tend to bounce off the edges of the page, and such crossings do not seem to alarm the child. Clearly, we need to distinguish between visual guidance and mere interest in observing what the hand with its marker produces. On the basis of her extensive collection of longitudinal data from 892 children, Haas has provided a very detailed account of the graphic development that proceeds from mere gestures that leave marks on the paper to the creation of lines, shapes, and an understanding of pictorial space, a highly ordered development (2003).

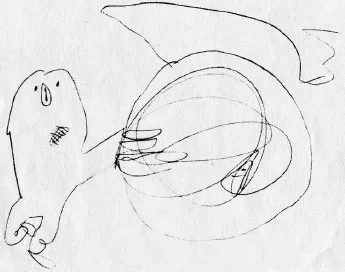

2. Action-Representation

“Man mowing the lawn.” Artist is a four-year-old girl who depicts the action, the lawnmower, and the noise of the motor as a whirl. (Courtesy, Rudolf Arnheim, Art and Visual Perception, 1974).

Beyond observing what his marks look like and how he can vary them, how does the child relate to the marks he creates? What—if any—meaning does the child attribute to his scribble pictures? Fortunately, when the child draws in the presence of an adult, he tends to accompany his actions with verbal utterances that shed some light on this question. At 2;1,1 Ben Matthews creates continuous overlapping spirals and comments, “It’s going around the corner.” As the paint lines vanish under additional layers of paint he remarks, “It’s gone now.” In this instance the child condenses several meanings into the single undifferentiated rotational action. The child’s own bodily movements, the trail of the brush on paper, and the movement of the imaginary object are all compressed into the visual-motor act of creating circular whirls. It appears that motor action and representational intuition are as yet fused, a state that Matthews identifies as “action representation.” We are witnessing a newly found freedom to label the action-in-progress. As the child creates his circular whirls, the motor rotation and his image of a moving and perhaps roaring object merge. Depending on the context, the child may identify the action-representation as “airplane” or “lawnmower” (see ills. 2; Arnheim, 1974, p. 173). In real life airplanes usually vanish along a straight path; in the two-dimensional plane the imaginary airplane is rendered by a continuous circular path, a gesture that captures the roar of the engine, as much as the actual ongoing motion of flying. The rotational motion attempts to make the path as well as the sound of the airplane visible. Matthews (1999) points out that actions in diverse domains tend to be synchronized; thus, for example, the pretend gesture of climbing a mountain and coming down is captured in the ascending and descending lines drawn on paper, accompanied by corresponding vocalization and changes in pitch. Such correspondences across diverse domains of action highlight an intrinsic synchronization that has its source in the sociobiological structures of the organism, and represents the beginnings of drawing as a meaningful and representational activity.

While Matthews interprets these action-verbalizations as “symbolic” behavior, from the point of view of graphic representation such actions indicate an early and primitive stage of development where ...