- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Money as Emotional Currency

About this book

This book explores the trace of the emotional undercurrent stirred by money from its beginnings in childhood to its consolidation into adult life, through love and work, for individuals and society alike, and with an emphasis on ordinary development, rather than on pathology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Money as Emotional Currency by Anca Carrington in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicologia & Storia e teoria della psicologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Emotional functions of money

Of all the ways in which thinking about money can be approached, historical accounts have been, and remain, the most prolific. On this matter, De Quincey is mercilessly clear in spelling out the appeal of this solution: “Failing analytically to probe its nature, historically we seek relief to our perplexities by tracing its origin” (1893, p. 43). Most books on money turn away from unease and unanswered questions, and embrace instead classification and chronology (e.g., Eagleton & Williams, 2007). The majority of writers on this subject take great pleasure in listing the many forms in which money appeared over time, as it found itself embodied in coins or shells, knives, salt, axes, skins, iron, rice, mahogany, tobacco, paper, and, more recently, plastic, and electronic impulses. Even the recently refurbished Money Room at the British Museum does not offer much more than a striking but brief succession of eras and currencies, one swift move from shells to plastic, as if to say, with a nod and a wink, “Isn’t money odd?” Yet, as Buchan (1997) puts it, while money is “of no particular substance at all” (pp. 17–18), in any given medium, and at any given time, money remains “incarnate desire” (p. 19), different and boundless for each person. It can at once convey and satisfy desire, even if only with a promise. Unlike other goods that can satisfy one desire at a time, money confronts not just one single need alone, but Need itself (Schopenhauer, cited in Buchan, 1997, p. 31).

Economics textbooks devote surprisingly little space to the nature of money, and focus instead on either elaborate policies that aim to manage money so that “more” takes the place of “less” in the relentless pursuit of economic growth, or complex financial techniques that can prove themselves so capable of generating such accumulation that little need for policy remains. As Galbraith (1975) rightly points out, “[T]he study of money, above all other fields in economics, is the one where complexity is used to disguise the truth or to evade the truth, not to reveal it” (p. 15), conveying the air of a Victorian novel about marriage that leaves out all mention of sex (Wiseman, 1974, p. 16). At the same time, as Buchan poignantly states, “whatever job it does, money does its job” (p. 182).

In the limited economics textbook space devoted to what money is and what it does, one learns something about the roles of money, as manifested in its functioning as means of exchange, unit of account, store of value, and, in some books, and some of the time, standard of deferred payment. The economics vocabulary also includes the concept of money illusion—not one usually uttered in public by policy makers. This refers to the tendency people have to think of money in nominal rather than in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. Disputed by some in terms of how much a policy-maker can rely on this being the case, I find this concept a highly insightful one, as we all know something about regarding money as capable of offering more than it can actually purchase.

I will explore each of the recognised functions of money in turn and posit that their universality and persistence in the external economy can be understood in terms of the corresponding internal economy on which these external functions map and in which they are anchored.

Money as means of exchange

As a means of exchange, money relies on its function as a measure of value, understood—in the vein of the prevailing rationalist view—as postulated on the basis of practical reason (Thomas, 2000). Money’s ability to represent and measure value makes it a suitable device for separating the constraints of barter, where both parties must want the goods of the other and be prepared to exchange theirs for it. Thus, the barter scenario is

I has A

J has B

I wants B J wants A

I and J swap A and B

I gets B J gets A.

In the absence of money, I and J make either this transaction or none at all. By turning this dyad into a triangle, money makes it possible for the seller to turn buyer in a separate transaction, without being tied to what their buyer could offer. Thus,

I has money

I wants C

J has C

J wants E

I and J swap money and C

I gets C

J gets money

J swaps money for E (later, elsewhere).

In day-to-day exchanges, money is an impersonal vehicle for hidden but highly personal transactions, a mediator that provides the illusion of proximity without the cost of intimacy—it creates links with others, but not contact. A vivid depiction of this as-if-ness in the world of business and economics is provided by Galbraith (1975) who reminds us that

in monetary matters as in diplomacy, a nicely conformist nature, a good tailor and the ability to articulate the currently fashionable cliché have usually been better for personal success than an excessively inquiring mind. (p. 315)

In this way, money functions as facilitator of transactions not only in our conscious reality, but also—and arguably more so—in the unconscious domain, as what is being avoided on one level is constantly enacted on another. One’s own relationship to money colours one’s perception of how others might relate to it. It is on this level that money stands for what everyone desires, making any financial transaction a revolving Oedipal configuration, or what Green calls a “generalised triangulation with a substitutable third” (cited in Diatkine, 2007, p. 653). Having a lot of money can make one feel emotionally wealthy, the chosen one, iterated winner of a life-long oedipal dispute. This is a common phantasy, shared by the economically poor and rich alike. Money offers the promise to alleviate castration anxiety for men: in phantasy, wealth becomes equated with virility, making any woman accessible. For women, it can act as a means of denying the insurmountable gender divide, with the phallic woman either enjoying her experience of domination over the relatively poorer man, or feeling wary about putting suitors off by parading her status, under the spell of a powerful unconscious association between femininity and the underprivileged/castrated (Yablonsky, 1991).

Each transaction offers a pair of a triangular configurations linking, on the one hand, the seller, the buyer, and money, where the desired object for the seller is money as mediator, and, on the other hand, the seller, the buyer, and the purchased goods or service, where the desired object for the buyer is the goods or service purchased. This triangular configuration is endlessly self-generating, with the buyer in one transaction becoming seller and buyer in many others, and likewise for the initial seller.

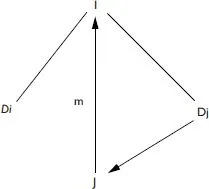

As illustrated in Figure 1.1, the seller I has Dj, which is the buyer J’s desired object. J gives I money (m) in exchange for Dj and I is now free to pursue his/her own desire, Di, through m. This configuration extends in all direction, in an expanding beehive of transactions that constitute a sort of molecular structure of the world economy.

Thus, each transaction offers the illusion of overcoming the oedipal barrier: the buyer (J at first) turns the inaccessible into accessible because s/he has the means (money) to get the desired object, with no obstacle in sight, as the rival (I) can be bought off and, thus, eliminated; the seller (I) acquires the means (money) that offers the promise of accessing his or her desired object in any future transaction with, say, K, as well as a replenishment of virility. As Yablonsky (1991) explores in detail, “both sexes are responsible for the perpetration of this money/virility myth” (p. 33).

If we were to apply this configuration to the payment of fees in psychoanalysis, it is easy to see how the patient bypasses others in the analyst’s life by paying for the analytic hour, accessing in this way—albeit temporarily—the dual relationship of phantasy; at the same time, the analyst gives up the hour, and other pursuits of desire that continue to exist beyond the confines of the session. An element of residual frustration about the limited power of money to secure such exclusivity characterises all transactions, but, in the particular exchange of therapy, this can be, and often is, addressed and explored.

Money as unit of account

As unit of account, money acts as a standardised unit of measurement across transactions. In the examples above, A, B, and so on had their own monetary value, m(A), m(B), etc. In the case of barter,

I has A

J has B

I wants B J wants A

I and J swap A and B

I gets B

J gets A,

we could argue that I values B more than J does, and J values A more than I does. When they make the exchange, each makes a gain by obtaining something they value more than what they had to start with. With money in place,

I has money

I wants C

J has C

J wants E

I and J swap money and C

I gets C

J gets money

J swaps money for E (later, elsewhere),

the buyer I pays m(C), some of which is then turned later by J into m(E). Although I parts with m(C) and J parts with C, arguably I values C more than m(C) in order to pursue the exchange. The same is true for J and his desired object, E. Also, J also values m(C) more than C, parting with C for the money that can be then used to obtain E.

Economics alone would propose that A=B in barter or C=m(C) in the money economy, or else the first exchange either would not take place, or an adjustment would occur in the prices and/or quantities until the exchange can occur in the moneyed economy. My argument is that it is the added internal sense of value and emotional investment (cathexis) that makes such exchanges worth pursuing. In other words, desire. Something about exchange and personal value attributed to goods or services is dealt with in mainstream economics, ironically enough using the concept of “indifference curves” to capture an assumed equivalence of preferences for the same level of “utility”. Yet, the entire exercise is as far from indifference as it can be, and definitely not purely utilitarian.

The one domain where the experience of this exchange has been the most explored psychoanalytically is that of the financial transactions between therapist and patient, around the issue of psychoanalytic fees and their payment in private practice. The focus of this literature is rather narrow, as it remains dominated by a specific set of themes: the presence or absence of fees and their the impact on the analytic experience (mostly in terms of associated resistance patterns), the level of fees and its relationship to the patient’s financial circumstances (from very poor to extremely wealthy), change in the financial circumstances of the patient during analysis, and changing the level of fees, payment for missed sessions, missed payment, and the collection of debt, payment by third parties, and the mechanics of the monetary transactions between patient and therapist (see Krueger, 1986 for a comprehensive coverage of these issues). Underpinning these themes is an unspoken assumption that the patient is endlessly fragile on all matters related to money and that, somehow, the impact of this on the analysis should be minimised rather than this being, alongside everything else, open to questioning and enquiry. By implication, analysts themselves are assumed to be invulnerable to such matters. Against the background of a detailed overview of these themes, Eissler (1974) recognises, with some degree of timidity, that analysts themselves cannot always keep their own attitudes towards money free from “irrational infusion” and that “a veil of unintended secrecy” covers the triangular formation of the analyst, fee, and patient. Also, in passing, he notes that psychoanalysis itself evolved, in historico-sociological terms, in conjunction with finance capitalism, offering, as it were, something from and for the wealthy and the upper middle class. Although he does not explore the consequences of this, it is as if he offers a possible explanation for the persistent reluctance in the profession to question this very history and its possible meaning.

Famously labelled by Krueger (1986) as “the last emotional taboo” (p. vii), the issue of money in psychoanalysis retains the quality of a “fiscal blind spot” (Weissberg, 1989). What seems to complicate the matter and compromise the availability of ordinary psychoanalytic thinking and insight is the very economic dependence of therapists on their patients. It is interesting to note that the decade that generated a wave of publications deploring “the striking paucity of discussions about the meaning of money” (Rothstein, 1986, p. 299) in psychotherapy was the 1980s, a time of visible increase in wealth and disparities in the western world, where the open and aggressive pursuit of money was a defining feature of society. It was as if the analytic profession was both wishing to catch up with this wave, and resentful of being unable to, because of the bounds that the nature of their work imposed on them. Perhaps it is no coincidence for this book to mark a return to thinking psychoanalytically about money, at a time when the recent global financial crises have left none of us unaffected and money has returned as cause for concern, this time provoking with its fragility rather than its promising abundance.

The recurrent discussion around the setting of the level of fees and their possible adjustment in relation to the patient’s financial circumstances reveals something about the lack of clarity and the discomfort some therapists have around the value they place on their own time and skills, especially as the issue of fees is also absent from most trainings (Lasky, 1984; Shields, 1996), thus perpetuating an avoidant stance. This resonates with Yablonsky’s (1991) finding that the positions of entrepreneur and helper that psychotherapists find themselves in are often in conflict, whereby “An inner tug of war ensues ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- About the Editor and Contributors

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter One Emotional functions of money

- Chapter Two Freud’s papers on money

- Chapter Three Money and childhood phantasies

- Chapter Four Phantasy in the world economy

- Chapter Five Love, money, and identity

- Chapter Six Money and desire: a Lacanian perspective

- Index