- 330 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women, Media and Consumption in Japan

About this book

First book of its kind to examine images of women in Japanese consumerism. Explores a variety of media targeted at women - in particular magazines, but also television, popular literature and consumer trends. Covers visual and print media.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women, Media and Consumption in Japan by Brian Moeran,Lise Skov in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Ethnische Studien. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTERPRETING OSHIN – WAR, HISTORY AND WOMEN IN MODERN JAPAN

In terms of television drama in Japan, Oshin (1983–4),1 produced by the Japanese national broadcasting corporation Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai (NHK – the Japanese BBC), was the success story of the 1980s. It achieved the highest levels of popularity since NHK began television broadcasting in 1953, and was the first Japanese television serial drama to achieve a global coverage, being seen in more than 40 different countries by 1993. The importance of Oshin is indicated in a full page article at the beginning of 1994, ‘Onnatachi no ōenka: NHK asa no rendora 50 saku’ (Cheering on women: 50 years of asadora), where it is given the largest photo space (Yomiuri Shinbun, January 1, 1994, New Year’s day supplement, p. 1).

In this chapter I will examine the reasons for the success of Oshin in Japan, and the complex factors that stood behind its production. I will propose that there was a complicated and contradictory ideological input from NHK, which meant that the conservative appeal made by the drama – its overt content – included at the same time the presentation of a more ambiguous and less socially conservative message. This relation between overt content and covert meanings may be seen to be a variation on the function of wrapping as noted by Joy Hendry (1993:8–26). It is the argument of this chapter that the conservative packaging of the drama allowed the more innovatory social message to gain currency.

The innovatory nature of the message is to be linked to the fact that Oshin was written and produced by women, who made use of a women’s genre, asadora (NHK morning serialised television novels), to make a powerful statement which reflected on the status of women in Japan, on women’s history, and on attitudes to past Japanese military aggression, which was the subject of public debate in 1982–3.

The most remarkable aspect to the drama from a western point of view is that it provides data to stand alongside Okpyo Moon’s (1992) contention that economic development in Japan can be allied to notions of a rise in women’s status. Oshin, the protagonist of the drama, went from rice farming to hairdressing to retail and eventually to owning supermarkets. However, at the same time as being held up as an independent ‘modern’ woman creating prosperity for her family, Oshin was also an embodiment of traditional Japanese female ‘virtues’, primarily self-restraint and self-sacrifice. She was, in a sense, well wrapped in a very traditional kimono. Okpyo Moon is surely right when she complains that: ‘in the study of gender relations, there has been [a] … powerful hindrance to the understanding of the reality of Japanese women: that is, the stereotypical image-making about Japanese women by western media as frail, submissive and mysterious beings’ (1992:206). Oshin provided a powerful demystification of this particular ideological package, for Oshin was neither frail, mysterious nor submissive, and the key to her success as a cultural icon was her ability to endure, a strength derived from her moral superiority to those who would inflict hardship upon her. Oshin’s embodiment of ‘endurance’ forms a continuity with the kind of spiritual suffering that the high school baseball teams undergo in the presentation of the baseball tournaments on television throughout Japan every summer, and Brian Moeran describes shinbō (endurance) as one of the keywords contributing to group ideology in Japan (1989:62–3, 71).

I will divide the chapter into four sections. In the first section there is a brief sketch of Oshin’s storyline. In section two, I will discuss the asadora genre. In section three, I outline the issues which were addressed by NHK in Oshin, which included the ‘school history book controversy’ over description of past Japanese aggression (sparked by complaints from China and Korea) and social concerns in the early 1980s relating to delinquent Japanese youth. The fourth section concludes the chapter by examining the complex ways in which naming takes place in Oshin, and the way that Oshin owed its success both to its ambivalent ideological stance and the way that it was able to tap powerful nationalist sentiments. Oshin was, in a sense, Japan.

Plot Outline – Oshin

Oshin is a historical drama, set at the end of the Meiji period and finishing in present time (at the time of screening 1983–4). Through a series of flashbacks working up to the present, it tells the life-story of the lead character Oshin, beginning with the opening of the seventeenth Tanokura (Oshin’s surname after marriage) supermarket, a link in the supermarket chain that Oshin and her children build from nothing after 1945. Oshin is absent from the ceremony. In the company of her grandson Kei, she has gone to revisit the village where she has spent her first seven years, and has suffered poverty and hardship, in order to reflect upon the ‘meaning’ of her prosperity. It is at this point that the flashbacks begin, with the first flashback sequence detailing the first time that Oshin was forced to leave home.

She was born in 1901 as the third daughter of a poor tenant farmer (kosakunin) in a village in the upper reaches of Yamagata prefecture’s Mogami river. Owing to the injustice of the tenant farming system (whereby a large percentage of the rice is surrendered to the landlord), the family is forced to live close to subsistence. After a particularly bad harvest Oshin is sent away for a year by her parents, effectively sold2 to a timber dealer to look after the baby and do chores in exchange for a bale of rice. The scene in which she leaves home has become one of the best remembered scenes in the drama. She is treated very harshly at the timber merchant’s. Just before she is due to return home, she is falsely accused of stealing. This is too much for her and she runs away, collapsing into exhausted sleep in the snow in the Yamagata mountains. She is rescued by a deserter from the army, Shunsaku, who teaches her that war is wrong. (The time that Oshin spends with him is discussed later in this chapter, and is a key to the drama as a whole). Following this section Shunsaku is shot in the back by military police as he carries Oshin home in the early spring. His death affirms his anti-military stance.

Some months pass, and Oshin decides that she has to sell herself into service in order to provide food for her ailing grandmother, Naka, and because her mother, Fuji, has chosen to work as a geisha at a nearby hot spring to provide vital family income. Fuji is a pivotal reference point in the drama. Oshin’s ability to endure is derived from her bond with her mother. Oshin moves to Sakata and is taken on by a rice dealer, Kagaya. The female owner of the business, Kuni, takes pity on her, and teaches her how to read and write, the basics of which she had picked up from Shunsaku. At Kagaya she also learns about class difference through her contact with Kayo, the daughter of the house.

In 1916 Oshin leaves Kagaya to be at the deathbed of her elder sister Haru, who has contracted tuberculosis while working in appalling conditions in a nearby silk mill (Hunter 1993:69–97). Haru encourages her to move to Tōkyō, which she does. She begins training as a Japanese-style hairdresser in Asakusa, a job which perhaps highlights the educative function that stands behind Oshin, since she is setting the hair of Japanese women in the traditional way, this being readable as a metaphor for the moral work done by the drama, which is teaching women to be ‘women’. But true to the complexity of the drama, it is an activity which serves only as one staging post on a long allegorical journey. There is more discussion of this later.

Before leaving Kagaya in Sakata, both Oshin and Kayo fall in love with Takakura Kōta, a wellborn young man who turns socialist in order to champion the rights of tenant farmers (i.e. Oshin’s family). Kōta proposes to Oshin, but Kayo intervenes. Kōta and Kayo leave together for Tōkyō and Oshin follows.

In 1920, after a few years in Tōkyō, Oshin meets and marries Tanokura Ryūzō, third son of a comparatively wealthy farming family from Saga in Kyūshū, who owns a business selling textiles. The marriage is opposed by both Ryūzō’s and Oshin’s family on the grounds of class difference. In the years that follow Oshin and Ryūzō build Tanokura Shōkai, a textile factory (there is an irony here with regard to the death of Haru, Oshin’s sister). However, soon after Oshin gives birth to her son, Yū, the 1924 Tōkyō earthquake reduces their home and the factory to rubble, leaving them bankrupt. They flee Tōkyō and join Ryūzō’s family in Saga, Kyūshū.

Oshin is cruelly mistreated by her mother-in-law, and this is the period of greatest misery for Oshin, compounded by the fact that Ryūzō sides against her. She suffers without complaint for a year, up until the birth of her second child. The baby dies within a few hours, weakened by the bad diet and harsh treatment. As soon as she recovers, she leaves her husband and his family, and returns home to the north with her son, Yū. Her abandonment of the family is the second turning point of the drama, and is similar to her meeting with Shunsaku. This was also the highpoint of the drama’s popularity, with a peak rating of more than 60 per cent. Up to the moment at which Oshin decides to leave, she has been a ‘model wife’ suffering in silence in the interests of family harmony, suppressing the self in the interests of the group, but by leaving she rejects this role and goes on to raise her children by herself and build a business on her own terms.

After a brief sojourn in Sakata, Oshin departs for Ise on the advice of Kōta, whom she has met again. In Ise she works as a fishmonger, peddling the day’s catch in the streets. This goes well, and her husband rejoins her. The business expands and they open their own store. Kōta reappears, taking refuge from the tokkō keisatsu, the Japanese secret police. Kōta is a communist, working to subvert Japanese imperialism. He is arrested when he goes to visit Kayo’s grave (Kayo had died in Tōkyō working as a geisha to pay off family debts). We are informed that he will be tortured and probably put to death.

This forms the prelude to the 1930s, with increasing militarization as a background to Oshin’s hard-won prosperity. Ryūzō changes from being a sympathetic young man (who buried his Kyūshū masculine (danji) pride and rejoined his wife after she had left him) to being an inflexible and authoritarian figure, sporting a Hitlerian moustache, and supporting Japanese expansion. War is pursued against China and the US, and within a short time the drama is filled with air raids, rationing and war. Yū leaves, and Hitoshi, the second son, though still under age, runs off to be trained as a pilot. The war comes to an end. The family is notified of Yū’s death, and Ryūzō, who had amassed supplies for the army, takes responsibility for his part in the war, and commits suicide. Hitoshi returns home. Yū’s friend Kimura visits the family and tells Oshin that Yū’s death was a miserable one brought on by starvation and fatigue.

The last section of the drama concentrates on the rebuilding of the prosperity of the family in the postwar years, and in particular the founding of Tanokura supermarkets. This development spans 35 years, and was aired in the last three months of the drama from January to March 1984. The drama closes with Oshin and Kōta (who had survived after all) walking side by side on a hilltop overlooking the sea in Showa 58 (1983).

Asadora genre and history

NHK morning serialised television novels (NHK Asa no Renzoku Terebi Shōsetsu – asadora, literally ‘morning drama’) were first broadcast in April 1961. To date there have been over 50 different dramas, Karin (October 4, 1993 – April 2, 1994) being the fiftieth. These television dramas are the most popular drama on Japanese television, and have been so ever since their inception. This is a factor of the time of screening, which is 8:15 a.m. (with a repeat showing at 12:45 p.m.); the nature of the audience, which has been largely married women; and the content and format of the dramas themselves, which has shown continuity since 1966 when the genre began to achieve a recognisable shape. In recent years, these three factors – time, audience and content – have all begun to change. This chapter will focus on one of the most important participants in that change: the immensely popular Oshin (April 4, 1983 – March 31, 1984), the most successful of all the asadora (and thus of all Japanese television dramas since television began in Japan).

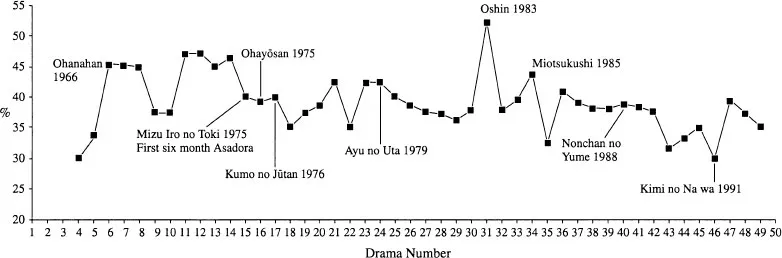

But before we look in detail at Oshin, it would be as well to consider how the genre became established in the 1970s, because Oshin was produced with very specific goals in mind; and its success was due in part to NHK’s desire to revitalise asadora which had been in comparative decline since the popularity of the late sixties, when the ratings were regularly over 50 per cent (see Figure 1.1).

Makita Tetsuo (1976) and Muramatsu Yasuko (1979) have provided the most authoritative discussions of asadora up to the screening of Oshin in 1983.3 The first asadora, Musume to Watashi (My Daughter and I), was screened from April 1961 for one year. It was designed to appeal to housewives who would be able to watch or listen to the story and dialogue as they did their housework. From the start, asadora included a narrator who filled in the gaps in the story and provided a non-visual continuity. In the first five years of asadora, NHK tried to fit well-known literary works into a televisual mode. The protagonist was often male, and the emphasis was on the man’s perception of his world and his family. The literary works used as source material were the ‘watakushi shōsetsu’ genre: autobiographical novels written largely by men. This early period of asadora was well summed up in an early publicity photograph for Tamayura (1965 – written by Kawabata Yasunari) showing Ryū Chishū with his wife and daughters gathered around him as he holds a haniwa (a clay figure from a burial mound) admiringly in his lap: the focus of the drama is male tradition and aesthetics which is to be cherished by the women, and of course the drama was produced, directed and written by men (Stera 1993.10.1). Kawabata himself put in a brief appearance in Tamayura, his first work produced on television, and it was the first time for Ryū, famous for his portrayals of Japanese father-figures, to appear on TV. Akatsuki, screened from April 1963 was similar: a story about a university professor who becomes a painter. Both of these were successful (there has rarely been an unsuccessful asadora), but it was felt that since the audience was largely female, a drama which spoke more directly to women’s experience would be more popular. This was given impetus by the realisation that the potential audience was so great: the Tōkyō Olympics of 1964 had caused sales of televisions to rocket, and by 1966 televisions were widely diffused. This must have been one of the factors inducing the production team to put together a drama which would have more appeal to women, and Ohanahan (1966) was the result: it had no originating ‘literary’ source, but was based on a piece in the women’s magazine Fujin Gahō and was written specifically for asadora (Makita 1976:86).

Figure 1.1 Graph of the popularity of Asadora 1961–1993

Source: Kantō ratings for Asadora 1961–1993 (data from Stera Magazine and Video Research K.K.)

Both Makita and Muramatsu point out that Ohanahan had a moulding effect on the genre. Ohanahan was not actually written by a woman,4 but ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- Editors’ note

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Hiding in the light: from Oshin to Yoshimoto Banana

- 1 Interpreting Oshin – war, history and women in modern Japan

- 2 Reading Japanese in Katei Gahō: the art of being an upperclass woman

- 3 Antiphonal performances? Japanese women’s magazines and women’s voices

- 4 Environmentalism seen through Japanese women’s magazines

- 5 Consuming bodies: constructing and representing the female body in contemporary Japanese print media

- 6 Cuties in Japan

- 7 The marketing of adolescence in Japan: buying and dreaming

- 8 Yoshimoto Banana’s Kitchen, or the cultural logic of Japanese consumerism

- References

- List of contributors

- Index