eBook - ePub

Mastering Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy

A Roadmap to the Unconscious

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mastering Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy

A Roadmap to the Unconscious

About this book

This book evolved from the First International Meeting of the Experiential Dynamic Psychotherapy Association on intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy. It will help readers to make use of the conscious working alliance with the patient to increase the unconscious part of the working alliance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mastering Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy by Josette ten Have-De Labije,Robert J. Neborsky,Josette Ten Have-De Labije in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Davanloo’s ISTDP, psychoneurosis, and the importance of attachment trauma

In the early 1960s, Davanloo decided to break away from the traditional psychoanalytic approach. In 1980, in his chapter, “A Method of Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy”, Davanloo briefly presented his method of ISTDP which was based on three systematic studies, involving psychotherapy with respectively 130, 24, and 18 clients with psychoneurotic problems.

His work, which from the start was all audiovisually recorded, was received with enthusiasm as well as with scepticism and criticism.

Now, more than thirty years later, we have many clinical studies and outcome research confirming the efficacy of this method.

Davanloo’s modification of analytic theory

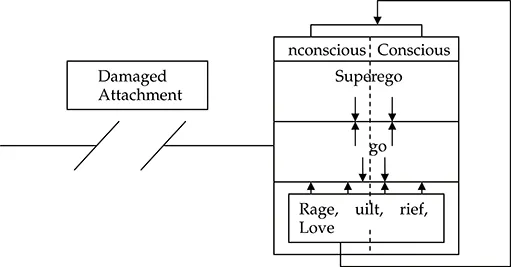

Davanloo (1990) describes that Freud believed that the superego establishes itself relatively late in developmental history and comes into operation after the resolution of the Oedipus complex. Evidence from his work with patients and from his clinical case studies has led Davanloo to modify analytic theory in emphasizing that it is already in the early months of life that the superego may play an active role in the causation and maintenance of neurosis. Neurotic disturbances arise as a result of a variety of possible traumatic experiences, involving damage to or disruption of the affectionate bond between the child and his caretakers. The child unconsciously reacts to this damage/disruption with a sadistic, murderous rage. It is this sadistic, murderous rage and the consequent loss (of the beloved murdered person(s)) which leads to guilt and grief as well as to punitive, sadistic reactions of the superego towards the child’s ego. The traumatic experience(s), murderous rage and its result(s), guilt and grief, are repressed into the unconscious. Various symptom patterns and character pathology develop as the ego of the developing child attempts to keep functioning under the mandate of the punitive/sadistic superego in such a way that it will not be overwhelmed by the impulses and feelings themselves, by anxiety, nor by the defences. The earlier, the more intense, and the more frequent the traumatic experiences, the more sadistic the impulses, and the more the ego will be trapped between the sadism of the id and the sadism of the superego, and the more the ego will become paralysed in managing the resistance of repression and the resistance under the mandate of the superego. Davanloo’s view on the development of neurosis is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Davanloo’s view on the development of neurosis.

The attachment bond and our mental health

Although Davanloo explicitly mentions the importance of the nature and quality of the attachment bond between child and caretaker in impacting the nature and quality of our mental health, he does not elaborate on this relationship.

Thanks to Ainsworth (1978), Bowlby (1969, 1980, 1988), and many other great minds of scientists and colleagues, we all know that the emotional bond, or attachment, formed between a (prenatal/postnatal) infant and its caretaker(s), is of considerable influence on the structure and functioning of the developing infant’s brain and the individual’s functioning in relationship with himself and others.

In the literature, four patterns of attachment are often distinguished: secure attachment, insecure-avoidant attachment, insecure-resistant/ambivalent attachment, and disorganized attachment (see, e.g., Hesse, Main, Abrams & Rifkin, 2003).

A secure and stable attachment lays the base for the developmental tasks of differentiation, separation, individuation, and the internal structure of object constancy from which our sense of self emerges. A secure and stable attachment will thus positively impact brain structure and functioning, thereby setting the basic requirements for the individual:

- to understand our own and other people’s longings, feelings, norms, values, opinions, and behaviour with love and care,

- to explore the outer world in a constructive way,

- to engage in meaningful interpersonal relationships, and

- to deal constructively with painful/harmful events of different interpersonal involvement.

Although there is a basic lifelong need for secure attachments, it may be clear that these attachment bonds will undergo changes in object, nature, quality, and intensity over the course of their development. Also, attachment bonds may develop with others such as siblings, extended family, teachers, friends, colleagues, lovers/partners, and pets.

An insecure, unstable, or disorganized attachment, whether caused by physical/emotional abuse, neglect, or emotional unavailability on the part of the caretaker will negatively impact brain structure and functioning, setting the basic requirements for the individual’s developmental and neurotic disorders (of course, the reverse is also true: neurological dysregulation, for example caused by birth, can also interfere with an attachment bond). The relationship between a) the features of a particular attachment bond, b) the particular phase of the individual’s development, and c) a later capacity of the individual to constructively regulate emotions, adapt to new situations, and learn is amongst other things due to the fact that the early social environment/caretakers has/have a direct impact on several neurobiological structures mediating the regulation of anxiety and emotions. For example, the first two years of life are critical for the growth of subcortical limbic areas and, because of the fact that the different structures of the limbic system are involved in mediating anxiety and emotions for the rest of the individual’s life, early harmful attachment events during such a critical period may have long-lasting effects.

The symptoms of untreated (attachment) trauma worsen over time and become more complicated as time passes, and it becomes more difficult to link present behaviours to the original (attachment) trauma. Feelings and behaviours linked to past traumatic (attachment) experiences are reinforced by new traumatic (attachment) experiences, and symptoms and destructive coping behaviours become more severe. Over time, acting out, repetition compulsions, and episodes of dissociation can become severely debilitating.

As mentioned above, it is in the interaction with our caretakers that we learn how to look at ourselves, to look at other people, to understand our own longings, feelings, behaviours, and those of others.

This implies that

- the specific features of the harmful/traumatizing attachment bond,

- the particular developmental phases experienced, and

- the subsequent specific neural dysregulation and memories of the several harmful interactions with each of the particular caretakers will become the basis for the specific (harmful) ways the adult person will have with respect to

- expectations of himself and of the outer world,

- understanding one’s own and others’ longings, feelings, norms, values, behaviours, and

- interaction patterns in intimate and social relationships.

The neurodevelopmental impact of violence in childhood

According to Perry (2001) and Schore (2003), a growing body of evidence suggests that exposure to violence or trauma alters the developing brain by altering normal neurodevelopmental processes. Bruce D. Perry’s clinical research (2001) has pointed out that trauma influences the pattern, intensity, and nature of sensory perceptual and affective experiences of events during childhood. The human brain develops and, once developed, changes in a “use-dependent” fashion. Neural systems that are activated in a repetitive fashion can change in permanent ways, altering synaptic number and micro-architecture, dendritic density, and the expression of a host of important structural and functional cellular constituents such as enzymes or neurotransmitter receptors. The more any neural system is activated, the more it will modify and “build” in the functional capacities associated with that activation. The more threat-related neural systems are activated during development, the more they will become “built in”.

Thus,

- exposure to violence activates a set of threat responses in the child’s developing brain,

- in turn, excess activation of the neural systems involved in the threat responses can alter the developing brain,

- these alterations may manifest as functional changes in emotional, behavioural, and cognitive functioning.

The degree and nature of a specific response to threat will vary from individual to individual for any single event and across events for any given individual.

In animals and in humans, two primary but interactive response patterns have been described: hyper-arousal (fight or flight responses) and dissociative response patterns. Dissociation is a broad descriptive term that includes a variety of mental mechanisms involved in disengaging from the external world and attending to stimuli in the internal world. This can involve distraction, avoidance, numbing, daydreaming, fugue, fantasy, derealization, depersonalization, and, in the extreme, fainting or catatonia. (See also Chapter Three on emotion regulation and Chapter Four on anxiety.)

If a child dissociates in response to a severe trauma and stays in that dissociative state for a sufficient period of time, it will alter the homeostasis of the systems mediating the dissociative response (i.e., opioid, dopaminergic, HPA axis). A sensitized neurobiology of dissociation will result and the child may develop prominent dissociative-related symptoms (e.g., withdrawal, somatic complaints, dissociation, anxiety, helplessness, dependence) and related disorders (e.g., dissociative disorders, somatoform disorder, anxiety disorders, major depression). If the child exposed to violence uses a predominately hyper-arousal response, the altered homeostasis will be in different neurochemical systems (i.e., adrenergic, noradrenergic, HPA axis). This child will be vulnerable to developing persisting hyper-arousal-related symptoms and related disorders (e.g., PTSD, ADHD, conduct disorder) (Perry, 2001).

Early trauma of course is not only synonymous with physical violence. What about emotional neglect or other kinds of emotional violence? The trauma of neglect is often cumulative and when an infant is experiencing chronic physical and/or emotional neglect (and we do see this neglect often in combination with physical abuse, this will not only result in impaired psychological functioning but also—as is the case with physical abuse—in changes in brain function (Schore, 2003).

We as humans can be tolerant and can love. But we can also humiliate, neglect, ignore, hate, destroy, and kill. There is violence across history, across cultures. Thanks to advances in technology our world has become small and we all have experienced or witnessed (e.g., via papers, broadcast, television) the horrors of violence and despite the wish of many amongst us, we have never been able to say a final goodbye to the violence that surrounds us and the violence of which we are a part.

Sadly enough the reality of our history, as well as the reality of this present time teaches us that we don’t need the violence of wars, natural disasters and so on to be confronted with traumatizing events on a daily basis.

Nevertheless, many people, including many therapists may underestimate the heterogeneity and complexity of violence, may underestimate the prevalence of physical and/or emotional violence in the home. Emotional violence may take the form of e.g., humiliation, devaluation, intimidation, neglect, ignoring, threat of abandonment or physical assault, blackmail etc. Taking care that a child is properly fed, clothed and is going to school doesn’t make one into a parent! Nor are schools providers of structure and safety from emotional/physical violence, which is exerted at school or at the homes of their students.

There is violence which is not recognized as violence, there is trauma which is not recognized as trauma nor recognized as violence and trauma by other family members. It is also not recognized ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Authors

- Preface

- CHAPTER ONE Davanloo’s ISTDP, psychoneurosis, and the importance of attachment trauma

- CHAPTER TWO The neurobiological regulation of emotion and anxiety

- CHAPTER THREE Emotion regulation and the role of defences

- CHAPTER FOUR Assessment of a patient’s anxiety

- CHAPTER FIVE Resistance, transference, ego-adaptive capacity, and multifoci core neurotic structure

- CHAPTER SIX Observational learning and teaching our patients to overcome their problems

- CHAPTER SEVEN The road to the patient’s unconscious and the working alliance

- CHAPTER EIGHT The independent variables

- CHAPTER NINE An initial interview with a transport-phobic patient

- CHAPTER TEN Steps on the roadmap to the unconscious and its application to patients suffering from depressive disorders

- CHAPTER ELEVEN Steps on the roadmap to the unconscious and its application to patients with somatization

- CHAPTER TWELVE Steps on the roadmap to the unconscious in a patient with transference resistance

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN Exiting the roadmap to the unconscious in the phase of termination

- APPENDIX Assessment forms

- GLOSSARY

- REFERENCES

- INDEX