- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

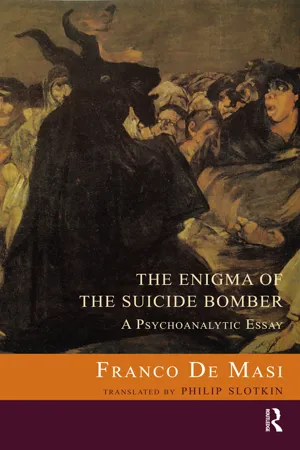

About this book

Why does someone resolve to take his own life in order to murder other people? What is the state of mind which allows him to commit such a monstrous act? This book explores the mental state that compels certain individuals to perform murderous, suicidal acts and emphasizes that, whereas a suicidal terrorist attack can be described as a crime against humanity, its protagonists cannot necessarily be classified as criminal or insane. There is no such a thing as a "typical" suicide terrorist - each attacker differs in age, sex, family status, culture, and even religion. Indeed, the common elements in suicide terrorism should perhaps be sought not so much in the individuals concerned as in the dynamics rooted in their group, family history or country. It may be extreme situations experienced by the group situations that are either objectively extreme or perceived as such that give rise to paradoxical behaviour at individual level. Psychoanalysis is well placed to consider this terrain.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Enigma of the Suicide Bomber by Franco De Masi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

A strategic aim

“The war of absolute enmity knows no bracketing. The constant fulfillment of absolute enmity provides its own meaning and justification”

(Schmitt, 2007)

Problems of definition

The word terror is of Latin origin and the concept refers to the sensation of unmitigated fear and anxiety that is unleashed by sudden confrontation with death. One of the presuppositions of terrorism is that individuals will be prepared to sacrifice their autonomy and independence for the sake of escaping from this fear. Arousing panic is indeed a way of securing the enslavement of another person. Submerging the other in death anxiety is the aim of terrorism, a form of violence directed towards the generation of fear. The object of this violence is to bend the victim to the terrorist’s will.

However, a definition that emphasizes the effect of fear on human beings is not an adequate political description of terrorism. Furthermore, present-day terrorism shows a different face from that of the past, owing to the destructive potential of modern weapons, and because the aims and the political instigators of terrorism are not the same. For this reason, it is difficult to give an unambiguous definition of the phenomenon of terrorism, which, as certain authors (e.g., Twemlow & Sacco, 2002) point out, is in fact influenced by the social and political values of the time.

At international level, too, it has not been possible to reach agreement on the definition of terrorism. The question had already arisen at the Munich Olympics of 1972, when a group of Palestinians abducted nine Israeli athletes. The United States’ draft resolution condemning terrorism was rejected by the non-aligned countries, which maintained that the struggle for national liberation was legitimate and instead condemned “repressive and terrorist acts by colonial, racist and alien regimes” (Haffey, 1998, p. 1). In spite of many attempts, the United Nations has been unable to arrive at a consensus on the definition of terrorism, precisely because of the irreconcilable disagreement between those member states (the Arab nations) that want to include, within such a definition, the concept of state terrorism, and others—the United States and Israel in particular—that cannot accept its inclusion.

A definition put to the United Nations General Assembly is as follows:

Any … act intended to cause death or serious bodily injury to a civilian, or to any other person not taking an active part in the hostilities in a situation of armed conflict, when the purpose of such act, by its nature or context, is to intimidate a population, or to compel a government or an international organization to do or to abstain from doing any act. [Article 2(b) of the International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism, 5 May 2004]1

The disunity and scope for discretion on this issue are also illustrated by the differences between individual Western nations’ views of Hezbollah (“the Party of God”), which is seen as a terrorist organization by the USA, the UK, and Israel, but not by other European states.

The assassinated former Prime Minister of Pakistan, Benazir Bhutto, described the dangers of these opposing positions, which represent different conceptions of political struggle, as follows:

Unless there is an agreement that terrorism knows no religion and no civilization, we could be on the precipice of a much more dangerous world…. Without a shared security mechanism and a definition of terrorism, the world could actually find itself in a holy war between Islam and the West. It’s a war that no one wants—except the extremists. [Bhutto, 2002, after Vedantam, 2003]

State terrorism?

To understand the nature and objectives of terrorism, it must first be distinguished from other, apparently similar phenomena. For example, some commentators consider terrorism to be an appropriate description of the incursions by Israeli tanks into the Palestinian territories and refugee camps, a response deemed as violent and destructive as a human bomb. Does an indiscriminate counter-terrorist response constitute terrorism? Is state terrorism equivalent to that perpetrated by someone who uses bombs to induce panic and to upset a balance of power? It was Robespierre who, in the name of the ethical state, first justified state terrorism and claimed moral acceptability for the assassination of political enemies. Since the French Revolution, other states—for instance, those with National Socialist or communist regimes—have based their political activity on terror, whether for the sake of ideology, the morality of the nation, or class interests.

Terror perpetrated by the state can be distinguished from terrorism proper according to the differences in the respective ways of achieving, maintaining, or extending power. In state terrorism, violence is perpetrated against ethnic or other groups within a nation itself in order to render already existing political power absolute. In this case, the actions of the governing party need not, at least to a certain extent, be supported by the population. It is the state that organizes genocide, while at the same time denying it and concealing the evidence of massacres. In terrorism proper, on the other hand, violence directed towards the imposition of political change or the seizure of power is explicit and even extolled.

Terrorism must also be distinguished from the actions of insurgent groups fighting to subvert the government of a given state.

Not only the political motivations of the terrorists, but also those of their political adversaries who define them as such, must be subjected to rigorous examination. After all, debatable and politically expedient use can be made of the term terrorism, for example when those prepared to use violence in fighting for a political cause are described as terrorists. Russia has defined the Chechen separatists as terrorists, China has done the same with the Uighurs, and India with the Kashmir separatists. In this connection, Vedantam (2003) invokes the Rashomon effect—a reference to Akira Kurosawa’s eponymous film, which tells the story of one and the same crime from contrasting and irreconcilable viewpoints.

Akhtar (in Hough, 2004, p. 814) distinguishes two types of terrorism: terrorism from above, used by government forces to intimidate, persecute, and destroy minorities; and terrorism from below, which acts against the state with destructive means. For the National Research Council (2002, p. 29), terrorism is “a strategy of the weak against the strong”. Both of these conceptions seem reductive against the background of the planet-wide dimension assumed by the phenomenon with the attack on New York’s Twin Towers.

What then are the salient differences between contemporary terrorism—described by Bettini (2003) as hyperterrorism—and that of the past?

Terrorism and genocide

Terrorism has traditionally been used by political minorities wishing to undermine a hated authoritarian regime. From the anarchic regicides of the eighteenth century to the anti-Tsarist conspiracies, history is replete with homicidal acts intended to cause terror and chaos. The aim was to attack and destroy the symbol of power: with a single pistol shot, the anarchist would kill the sovereign and obliterate his charismatic image, with a view to destabilizing the entire tyrannical order.

Later, even democratic regimes were affected by the phenomenon; examples are the wave of bloody slaughter experienced in Italy in the 1970s, and Basque, Irish, or Chechen terrorism. In these cases, the terrorist attacks were not merely military actions, but were principally aimed at drawing the national or international community’s attention to the relevant group’s struggle. Coverage in the international media would ensure that the acts were seen as duly spectacular. As Benjamin Netanyahu, Prime Minister of Israel at the time of writing, rightly pointed out some years ago, without media coverage acts of terrorism would resemble the proverbial tree that falls silently in the forest.

The face of terrorism has changed in recent years. Mass slaughter, already a feature of the Algerian struggle for independence, or of the “strategy of tension” in Italy, is now employed so systematically that it has virtually become a strategy in itself. Its massive scale admittedly places terrorism on a par with genocide (of the Jews, the Armenians, or specific ethnic groups in the recent conflicts in Rwanda or Bosnia); however, the difference is that genocide is an action planned by the state with the aim of exterminating an ethnic group deemed to be hostile or different, whereas even large-scale terrorism is manifestly not directed towards extermination of the enemy. Its purpose is to strike indiscriminately, to arouse anxiety, and to confuse and disorientate the target group. The action must be spectacular in order to give rise to panic, and the destruction must be unpredictable, so as to weaken the enemy psychologically and to paralyse him.2

However, this aim is achieved only in the immediate aftermath of the attack. Once the panic is over, the target population defends itself and mobilizes in order to neutralize the danger.

In the case of genocide, on the other hand, examination of the victims’ emotional reaction reveals the surprising fact of their passivity. Systematic violence by the state (state terrorism) gives rise to a mental condition that inhibits any reaction. From the extermination of the Armenians in Turkey to the genocidal policy of Stalin in the Soviet Union, from the destruction of the Jews in Europe to the massacres perpetrated by Pol Pot in Cambodia, “ethnic cleansing” in Bosnia, and the extermination of the Tutsi community in Rwanda, millions of people have been systematically slaughtered without any evidence of resistance. Genocide can be carried out, and terror can spread, because the persecuted community represents a minority within a state, lacks political control of the armed forces, and is therefore unable to defend itself.

The aim of terrorism is predominantly political. It seeks to provoke utterly indiscriminate reprisals, so as to compel the enemy to radicalize its own position and to generalize repression. In this way alone can more and more people be induced to see violence as the only possible way forward. Terrorism is intended precisely to divide and to arouse conflicting emotions. Its victims fear and hate it, but at the same time there are others who, while not sympathizing with it, consider it justified. According to certain strands of public opinion, its reasons are comprehensible, and they defend it as a possible instrument of struggle. Some years ago, the Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfuz, a winner of the Nobel prize for literature, stated in an interview with the New York Times that he disapproved of suicide attackers, but added that he could understand them.

To understand the specificity of the terrorist strategy, it is essential to bear in mind that its aim is to provoke the enemy and heighten the level of conflict. Considered in these terms, the psychology of terrorism is much more sophisticated and complex than repressive terror exercised by the state. Furthermore, terrorism relies on this blindness for its success.

The rationality of terrorism

Terrorism exists in different forms according to its immediate purpose. Robert Pape (2003) distinguishes three types on the basis of their short-term objectives.

The first is demonstrative terrorism, whose aim is principally to gain publicity, to recruit more activists, and to force the government to make concessions. Examples are the terrorist groups in Northern Ireland, or the Extraparliamentary Left in Italy. Their action takes the specific forms of hostage-taking, aggression against individual politicians, or bomb blasts of which prior warning is usually given.

The second type is destructive terrorism, which is more directly aggressive in nature and seeks to inflict losses on its opponents by killing their leaders. Examples are the Baader-Meinhof gang, the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The most successful group in the recent past was surely the now defeated Tamil Tigers, who assassinated the Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in Madras in 1991 with the aid of a young female suicide bomber.

Thirdly, there is suicide terrorism, in which the suicide-to-be bears his cargo of death with a view to maximizing the damage caused.

A broader definition of a suicide terrorist will include not only those who kill themselves in order to kill others, but also those who expect to lose their lives during the course of an attack. Baruch Goldstein is an example of the latter. Before embarking on his mission, he left a note for his family stating that he did not expect to return. He did indeed then die while killing a group of Palestinians in Hebron in February 1994. This second and less frequent type of suicide terrorist is not linked to any organization. The psychological dynamics underlying their acts are also very different from those of suicide terrorists belonging to organizations with a hierarchical structure, who sacrifice their lives for a political purpose.

Considered in these terms, suicide terrorism proper is not the fruit of irrational impulses or fanatical hatred (although certain aspects of these are never lacking), but pursues strategic objectives.

Pape (2003) shows that this was the situation in Lebanon and the Gaza Strip, as well as in Sri Lanka, where the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) recruited members from the Hindu population and had a Marxist-Leninist ideology.

Even though many suicide terrorists may, at first sight, appear irrational or fanatical, this is not true of the political aims of their leaders. Nor has the policy of suicide terrorism failed to achieve results: in Lebanon, the Franco-American forces withdrew in 1983; Israel was compelled to pull out of that country in 1985 and of the Gaza Strip in 1994–1995; while Sri Lankan government forces withdrew from certain parts of the country in 1990.

According to the same author, who possesses one of the largest databases on suicide attacks, these results were not solely attributable to terrorist action, which, however, was certainly a factor in their achievement. He concludes that almost all suicide attacks are not motivated by religious fanaticism, but form part of a deliberate strategy of compelling states to withdraw troops from territories held to be illegally occupied. In other words, according to Pape, suicide terrorism is not irrational, as some earlier commentators (Kramer, 1990; Merari, 1990; Post, 1984) believed, but is an extreme form of what Thomas Schelling (1966) called the “rationality of irrationality”.

Ideological terrorism

The matter is, in fact, probably not as straightforward as Pape’s description suggests. There may be a difference between terrorism directed towards the achievement of an explicit goal (as perhaps with Lebanese or Palestinian terrorism) and another form that is more radical and destructive, has no demands, and has no wish to negotiate. The latter type (which includes the 11 September attacks) has its origins in the totalitarian ideology of jihad or the al-Qaeda organization, lacks a precisely defined objective, but presupposes an implacable ideological struggle waged without quarter.

The three forms of terrorism enumerated by Pape must therefore be supplemented by a fourth—namely, international ideological terrorism, the most dangerous type of all. Ideological terrorism is not confined to a specific geographical area—and therefore does not correspond to a state or a nation—but is supranational in character. Its aim is to create a war mentality so as to provoke acts of retaliation at international level, thus triggering a bloody global conflict.

From this point of view, the ideological fanaticism of its leaders is not attributable to the madness of an individual or group, but is in fact the expression of the lucid aim of imposing power by means of a planet-wide bloodbath. For this reason, whereas the main aim of traditional terrorism was to secure political concessions, since 11 September the message of international ideological terrorism has been that of all-out war. Given this aim, it is misleading and dangerous to respond to ideological terrori...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- FOREWORD

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER ONE A strategic aim

- CHAPTER TWO Psychoanalytic contributions

- CHAPTER THREE Origins and profile

- CHAPTER FOUR Martyrdom and the sadomasochistic link

- CHAPTER FIVE Murder–suicide

- CHAPTER SIX The network and filicide

- CHAPTER SEVEN The female suicide bomber

- CHAPTER EIGHT Trauma

- CHAPTER NINE Dehumanization

- CHAPTER TEN Dissociating emotions

- CHAPTER ELEVEN Unique identity and omnipotence

- CHAPTER TWELVE A cannibal God

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN Terrorism: reversible or irreversible?

- Conclusions

- NOTES

- REFERENCES

- INDEX