- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Old Testament Stories with a Freudian Twist

About this book

This collection of the author's last essays are writings that he was working on from 2006 up to and during his final illness. They take as their starting point stories from the Old Testament. For the author, the Bible provided a great inspiration for analysis, reflection, and speculation. His own distinctive voice is evident in every essay. Chapters include: Jubal: A discursive meditation on music and its origins; Jacob's wrestling match; The judgment of Solomon; Abishag: The lure of incest; and The nakedness of Noah.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Old Testament Stories with a Freudian Twist by Leo Abse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

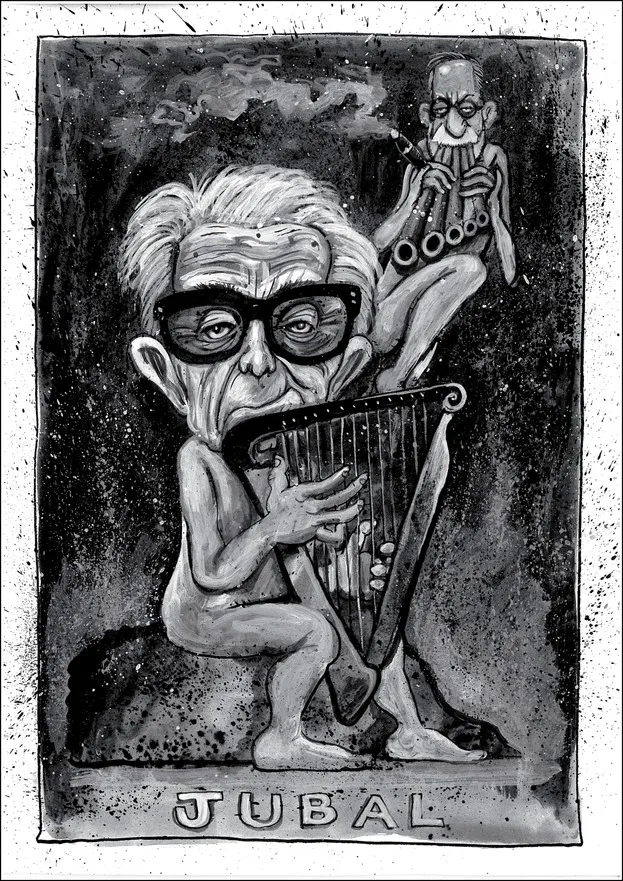

Jubal: A discursive meditation on music and its origins

As a little boy I would sit at the knee of my Talmudic grandfather and there he would spell out to me enchanting tales from the Midrash Haggadah, that roving rabbinical commentary beginning five centuries before Christ on the anecdotal and legendary portions of the Scriptures. And, sometimes, although rarely, to illustrate the stories, he would gravely unwrap the one icon permitted in his austere home where otherwise, in accordance with the Commandments, no hint of a graven image was to be found. No Catholic viewing the reliquaries in the shrines of Christendom could have gazed more reverentially at the bones of saints than did my grandfather and I when, with the containing silver box opened and the purple velvet covering removed, the treasure, a polished gleaming white ram’s horn, came into view. This was the sacred shofar, to be blown in the synagogue only on the most solemn days of the Jewish religious calendar.

Such a shofar, I was instructed, at the time of the great Sinai the-ophany, was heard by my ancestors heralding the Covenant between God and the Hebrews who, in return for their affirmation that God was One, that gods were worthless idols, would be forever the Chosen People. And I heard too the less forbidding, more magical, tales of the powers of the shofars: how, when blown, the enemies of my forebears suffered defeats, their sounds bringing down even the mighty walls of beleaguered Jericho. And how, when heard with a clean heart, their notes would bring hope of the fulfilment of Isaiah’s vision of the in-gathering of all of us, my grandfather and I, exiled in the diaspora:1

And it shall come to pass in that day, that the great trumpet shall be blown, and they shall come which were ready to perish in the land of Assyria, and the outcasts in the land of Egypt, and shall worship the Lord in the holy mount at Jerusalem.

But my protective grandfather shielded me from the knowledge of the potential awesome punitive power of the shofar: that sometimes it was not a white or fawn ram’s horn but a black one, named Cheres Shofar. Such an occasion was the great excommunication, when, on 27th July 1656, in solemn ceremony, accompanied by terrible curses, the shofar was sounded at the Amsterdam synagogue proclaiming Spinoza, one of the greatest minds Jewry has given the world, to be an apostate, a heretic and outlaw.

There was, however, another date much more awesome that my grandfather, far from concealing, vividly impressed upon me: 9th Ap—17th August AD 70. This was the date the Temple was destroyed, the day when the fate of Jewry was decided for 2,000 years: from thereon they were to be dispersed, homeless among the nations. Until that date, in the Temple, apart from the original and simple ram’s horn, more sophisticated musical ensembles had evolved: flutes and zithers, cymbals and triangles, and many percussive wind and string instruments were sounded at the great feasts of the Ancient Jews to enhance the solemn mood of the assembled congregation. But from the day the Temple fell there were to be no musical rejoicings in the synagogues of the diaspora. There the silence was to be broken only by the sound of the oldest wind instrument known: the sound of the prehistoric shofar; each year, and still today, on the fast-day the ram’s horn is blown and the loss of Solomon’s rebuilt Temple is mourned.

The renunciation henceforth of all musical instruments save the shofar reveals how profoundly Ancient Jewry experienced their loss; they were castigating themselves for the sins which had brought down upon them the wrath of the Lord who had found them no longer worthy of His Temple. To expiate their wrongdoing, to regain their Father’s love, they were ready to give up their most precious possessions, even to end a musical tradition that had lasted for most of a recorded history of almost 4,000 years. No people, musical scholars assert,2 have a history where music is more mentioned than that of the Jews. The Bible tells us that under King David, out of the tribe of 38,000 Levites, 4,000 were appointed as musicians. Josephus in the first century BCE, in his History of the Jews, is no doubt exaggerating when he refers to there being 500,000 musicians in Palestine prior to the dispersal, but that citation indicates how persistent had been, over thousands of years, the importance of the contribution of music to the enrichment and stabilization of ancient Israelite culture.

When the time came for me, in the years leading up to my bar mitzvah, to go regularly to chedar classes, the Hebrew classes where I would be taught to translate the Pentateuch, I discovered more about the shofar and about its inventor. In Genesis3 the “father of all such as handle the harp and organ” is named as Jubal, a name that comes from the same Hebrew root as jôbél which signifies ram’s horn or trumpet; the man whom the Bible names as the inventor of music, as soon as he is revealed to us, is identified with the shofar. The reference to Jubal is laconic, too laconic not to arouse suspicion of some concealment: such reticence is notably absent in the elaborate recitals of the discovery of music and the invention of musical instruments contained in the myths of the Chinese, Indian, the Egyptian and Greek cultures. And, alone among the nations, the originator in the Hebrew legend is declared to be a mere mortal, not, as in all other cultures, a god or demi-god.

The Greek version is more conventional and well illustrates the general portrayal of the antics of the gods that accompanied the birth of music. It is Hermes, the boy wonder, son of Zeus and Maia, born in a cave in Arcadia, who is credited with the invention of the lyre. The mischievous boy, on a nocturnal adventure, found a tortoise in his path. He picked it up and with a bright chisel emptied the shell. Around it he stretched oxhide with the aid of reeds and arranged over a bridge seven strings made from sheep gut which then gave out harmonious sounds. It was the first lyre. The boy had upset the god Apollo by stealing his heifers. To effect a reconciliation, he first played the lyre to calm and seduce the irate Apollo and then, as a gift, gave the lyre to the charmed Apollo. From then on, the two gods became locked in an intense and never-broken friendship, and Apollo became the god of music. The homoerotic elements of the tale are emphasized by an addendum: subsequently, Apollo used his musical endowments to seduce Daphnis, son of a nymph by Hermes, a tale of paedophilia that can be found exquisitely portrayed in Perugino’s painting in the Louvre.

These transgressive, erotic, and incestuous tales are of gods—and gods, unlike men, know few constraints. In the Hebrew story, the inventor of music is a man and notably placed under the constraint of his inheritance. Jubal’s mortality is stressed: his genealogy is painstakingly set out. He is no god but a man burdened with a tainted ancestry, a direct descendant of the most notorious murderer in history: the man upon whom God had embossed a mark, never to be erased, Cain, Jubal’s progenitor. The family tradition was well maintained by Jubal’s sibling, Tubal-Cain, the first armament manufacturer, the inventor of edged iron blades “and instructor of every artificer in brass and iron”.4 Jubal had a half-sister too, Naamah, whose name, the Mishnah tells us, refers to song. This was a family well-equipped to render, with vocal accompaniment, the most stirring of martial tunes. It was the talented trio of this family who bequeathed to their descendants the vividly descriptive Song of Moses to be sung by the Children of Israel to the accompaniment of Miriam’s dancing and cymbal-playing on the shores of the Red Sea as they revelled in the drowning of Pharaoh’s hosts. The bloodthirsty libretto spells out the message of the Song: “The Lord is a Man of War”.5

The inventor of music thus emerges as coming from a family of terrifying violence, a family who worshipped that belligerent God. Jubal is not presented as a man of peace. Pulsating behind the two short, bland sentences revealing the identities of the authors of music and of arms, one hears a menacing beat; the chronicler hesitates to tell us more directly what is the source of the threatening sound, but etymology reveals all. Jubilation is the emotional component of triumphalism, the celebration of ruthless, homicidal victory over an enemy.

It is therefore not a disconcerting interpretative irrelevance that the two Biblical paragraphs naming Jubal and Tubal are immediately followed by the recording of a violent outburst by their father Lamech who triumphantly declaims to his wives his prowess as a killer:6

... Oh hearken my wives,

You wives of Lamech give ear to my speech.

For a man have I slain for my wound,

a boy for my bruising.

For sevenfold Cain is avenged,

and Lamech seventy and seven.

Jubal comes from a criminal family, quick to take offence, whose hands are dripping with blood.

No wonder that as a little boy, when, on the Day of Atonement I heard the horn of Jubal sounded in my grandfather’s synagogue, I trembled: there was murder in the air. I would feel the fear of the silent adults standing around me as, at the culmination of the fast-day, the shofar, in three sets of sounds, long, fearsome, mourning, and intimidatory, was blown by the cantor. All in the congregation were desperately hoping that he would not falter, that, despite the difficulty of playing such a crude instrument, the sounds would nevertheless emerge clear and strong for then the evil within themselves would be held at bay, that, as the cabbala has it,7 Satan would be humiliated. Only then could they hope that they would benefit from the absolution contained within the benediction bestowed upon them before the shofar had been blown by the presiding rabbi:

Praise be the Lord our God, the King of the Universe, Who sanctified us with His precepts and commanded us to hear the sound of the shofar.

And then, having observed the commandment and been granted the privilege of hearing, unmuffled and pristine, the sound of God’s trumpet, thus temporarily sanctified, both young and old relaxed. As the final note of the shofar faded away, the eerie tension that had enveloped everyone in my grandfather’s provincial synagogue dissipated.

Our supplications had been heard and answered. Our abnegations had not been in vain; in our prayers commencing the evening before and continuing during the long day of fasting, we had begged that our estrangement from God should end. I too, in my pre-pubertal unbroken voice, had added my pleas and had recited with the whole congregation the libretto the psalmist had required should accompany the compositions of Jeduthun, the chief musician of the Temple:8

Hear my prayer, O Lord, and give ear unto my cry; hold not Thy peace at my tears; for I am a stranger with Thee and a sojourner, as all my fathers were. O spare me, that I may recover strength, before I go hence, and be no more.

And I too had followed the example of my elders and beat my breast six times as I had read the confessional Al chate prayer categorizing the sins my people had committed; at ten years of age I did not understand the nature of those sins but still it was as a penitent that I pleaded for forgiveness:

For the sins which we have committed against Thee by compulsion; for the sins which we have committed against Thee wilfully; for the sins which we have committed against Thee secretly; for the sins which we have committed against Thee publicly; for the sins which we have committed against Thee through ignorance; for the sins which we have committed against Thee presumptuously.

I did not then know, as I do now, that a euphemistic quality pervades that categorization of our transgressions, that by appearing to present an all-embracing compendium of our sins, the specific and most serious of Israel’s crime could be hidden beneath the generalizations: it is the crime so guilt-ridden that a recall would be too onerous to be borne by the individual. The Al chate prayer, therefore, is not to be read silently: it is to be proclaimed, not whispered in a confessional booth. It is not a private prayer, it is a collective response, an acknowledgement of a collective guilt. Even a hint of personal unshared responsibility would induce so crushing a sense of guilt that it could not be borne by an individual. The group had committed the crime, the group must carry all the blame. And on the Day of Atonement by group flagellation, by breast-beating, by ostentatious acceptance that their dispersal throughout the nations was punishment well-deserved, for they and their fathers had turned away from the Lord’s goodly precepts and ordinances, they vainly hoped to expiate their terrible crime while leaving it unnamed.

These stratagems failed. The acknowledgements of guilt are too qualified, too tentative, to ever earn them total absolution. The cunning early Jewish Christians tried an avoidance tactic to achieve that end: they displaced the crime by crucifying the son. But stubborn mainstream Jewry scorned the camouflage: they knew the true name of the victim even although they could not utter it. By that omission the confession fell short of full disclosure. Only a remission, not an absolu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter One Jubal: A discursive meditation on music and its origins

- Chapter Two Jacob’s wrestling match

- Chapter Three The judgment of solomon

- Chapter Four Abishag: The lure of incest

- Chapter Five The nakedness of Noah

- Index