![]()

Part 1

From projective identification to the psychoanalytic process

![]()

Chapter One

Projective identification with internal objects

A. Projection and projective identification

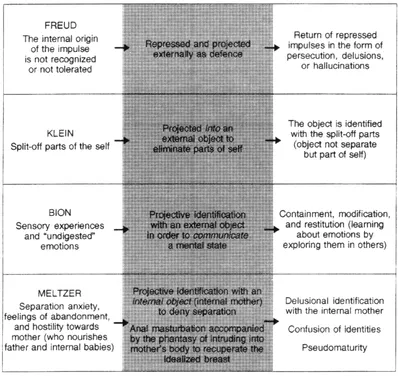

A term that frequently recurs in Donald Meltzer's work is that of projective identification. It is found both in this form (that is to say, according to the Kleinian definition) as well as coupled with other words in order to describe specific, sometimes pathological, situations. Before examining in this chapter the mechanism of projective identification with internal objects—one of Meltzer's basic theoretical concepts—I shall briefly review the concept of projection in the work of Freud and that of projective identification in Melanie Klein's and W. R. Bion's. Many other authors have discussed projective identification, but here I refer only to those whose ideas have influenced and have been further developed in Meltzer's work.

According to the classical Freudian theory, projection is a defence mechanism in which a person attributes to others tendencies, desires, and so forth that he or she does not recognize in him/herself. In a letter to Wilhelm Fliess in 1895, Freud (1950 [1892-1899]) considers projection as normal—"if something prevents us from accepting the internal origin [of an experience] we naturally grasp at an external one"—but he also considers it as the typical defence mechanism of paranoia, in which the primary experience is repressed, projected into somebody else, only to return in the form of persecution, delusions, or hallucinations.

Klein advanced the concept of projective identification with reference to the paranoid-schizoid position, which she described as the first phase in the infant's life. This phase is characterized by the infant's need to eliminate anxiety and destructive impulses through the defence mechanism of splitting. The split-off parts are projected into an object, which is then identified with these split-off parts. For instance, if the infant has projected destructive impulses into the breast, the breast is felt to have been destroyed and, in situations of anxiety or frustration, the feeding relation may be experienced as taking in something damaged. To quote Klein (1946), "In so far as the mother comes to contain the bad parts of the self, she is not felt to be a separate individual but is felt to be the bad self" (p. 8). This process is counterbalanced by another defence mechanism, that of introjection of the good object. Once the good object is internalized, it not only defends from anxiety but also lays the foundations of the ego.

Projective identification can be massive if the whole self is projected into the object; however, Klein usually refers to projection of parts of the self. Hanna Segal (1979) points out that, in the Kleirtian view of projective identification, it is not necessarily an impulse that is projected. Parts of the self or of the body (for instance, the baby's mouth or penis) or body products (faeces, urine) may also be projected, in phantasy, into the mother's body, which is then identified with the projected parts. This occurs in order to evacuate unwanted parts of the self, or to control the object, or to damage and take possession of the object. Good parts may also be projected into the object; in this case, the object is idealized and the re-introjected idealized object becomes the basis for narcissism.

Whereas Klein stressed the defensive aspects of projective identification, Bion, as Betty Joseph (1987) has shown, added the dimension of communication in the primary mother-baby relation. In Bion's view, projective identification cannot be considered simply as a phantasy concerning an object, but is seen as an operation aiming at communicating something to an object that is capable of containing the phantasy. The containing object receives and modifies the projection, which can then be returned to the individual without the original anxiety. For Bion, projective identification is considered as a way of learning about one's own emotions through exploring them in others. The infant projects (or evacuates) its sensory experiences and its primitive emotions, which are then transformed by the mother's thinking (alpha-function) into more tolerable emotions, and can subsequently be used as elements of experience (alpha-elements). In this theory, projective identification plays a fundamental part as the source of symbol-formation and thinking in the infant (through the mother's reverie and alpha-function, which contain and give meaning to emotions). The same process is repeated in the analytic relation (through the patient's projections and the analyst's countertransference and interpretations).

Meltzer refers both to Klein's definition and to Bion's concept of projective identification, but he develops them in various directions. Throughout Meltzer's work, reference to different kinds of projective identification can be found, starting with massive projective identification.

B. Massive projective identification

Massive projective identification is described by Meltzer as a defence mechanism resorted to in order to avoid separation anxiety. Massive parts of the self are projected into the object and become confused with the object, thus erasing the boundaries between the self and the object and enabling the denial of separation. This concept of massive projective identification, to which Meltzer refers in his first works (1966,1967), is later abandoned in favour of a more qualitative than quantitative description of projective identification. Meitzer is no longer interested in how much of the self is projected into another person, but into which part of the other person projection and identification take place. His subsequent descriptions (1986c, 1992) emphasize the characteristics of the specific internal space in which intrusion and confusion occur, and less importance is given to massive projective identification as the need to merge with and return into the mother's body. The inside of the mother's body becomes differentiated, in Meltzer's theory, into various compartments, each of which can be intruded into, at the risk of remaining claustrophobically trapped therein. This aspect is discussed here in the chapter on Meltzer's theory of the claustrum (chapter seven).

The above specification into different spaces of intrusion does not, in my opinion, invalidate the concept of massive projection identification, which is useful to define the general tendency (particularly in psychotic and borderline patients) to cancel the boundaries between self and object in the face of separation anxiety. In the countertransference, this produces the sensation of being massively invaded by the patient, which can later be analysed in order to define the area of intrusion. This brings us to another aspect of projective identification: that of intrusion with internal objects.

C. Intrusive projective identification with internal objects; pseudomaturity

Projective identification can be used not only to project into external objects, but also into internal objects. According to Meltzer, this is what happens when the child explores the inside of its own body while phantasizing intrusion inside the mother's body. Meitzer is referring to an unconscious phantasy of intrusion into an object that is confused with the self.

In his paper on projective identification with the internal object (1966), Meitzer discusses the relation between the child's anal exploration and projective identification with the inside of the mother (the idealized contents of the rectum). However, as will be seen later, different spaces can be used for projective identification of parts of the self.

In order to understand the concept of projective identification with an internal object, Meltzer's illustration of the child at the beginning of the anal phase is most clarifying. In this phase, the child has been weaned, mechanisms of splitting and idealization operate less adequately, mother demands more autonomy and sphincter control, and the child feels threatened in reality or in phantasy by the birth of a new baby and consequently may feel abandoned by its mother and hostile. The child's own body as well as that of the mother are experienced as containing bad, dirty, and dangerous parts. The lost breast is idealized (as the source of nourishment and of all good feelings), and the child phantasizes recuperation of the idealized breast inside his own body. This occurs, according to Meitzer, because anal masturbation is accompanied by the phantasy of penetrating mother's body, to steal the idealized contents of the rectum, thus creating a delusional confusion of identity between the inside of the child's own body and that of the mother. To quote Meitzer "the baby's bottom and that of the mother are confused one with the other and both are equated with the mother's breasts" (1992, p. 15).

This delusional identification with the inside mother erases the differentiation between the child and the adult, for the child need no longer separate from the mother but, in a certain sense, becomes the mother. These children behave like little adults: they adapt to external requirements and are often model children, but their adjustment is superficial. This character constellation, which arises from projective identification with the internal object, is defined by Meltzer as pseudomaturity. The aim of this defence mechanism is to deny separation and dependency on the adult by becoming confused with the idealized object. Therefore, these children grow up without developing a real emotional maturity or individualization, without ever facing their oedipal conflicts, without emotionally separating from the internal object with which they are identified. Meltzer (1967) has compared this constellation to Winnicott's (1960) "false self" and to Deutsch's (1942) "as-if" personality. Pseudomaturity appears in fact very similar to the "false self" described by Winnicott. In my opinion, however, there are substantial differences between pseudomaturity and the "false self", and it is important to keep these in mind in the therapeutic relation. In Winnicott's theory, the "false self" is built up on the basis of compliance with the envirortment's requests. The function of the "false self" is to defend and hide the "real self". Therefore, a splitting process occurs in which the "false self" may be organized at different levels, ranging from an extreme pathological level— at which the "false self" becomes the "real self"—to a more "normal" level—in which the "false self" represents one's social attitude—with other levels in between. Pseudomaturity, on the other hand, is closely linked with the beginning of the anal stage, which usually coincides with requests for autonomy on the part of the environment. As we have seen, the aim of this defence mechanism is to deny dependency and separation: hostility and separation anxiety cause the child to identify with the internal idealized mother. Therefore, at the basis of pseudomaturity, we will find confusion of identity between the inside of the self and the inside of the mother, due to intrusive projective identification.

In children, the pseudomature personality is characterized by model behaviour towards adults both at home and at school, where they are good achievers and show high verbal capacities, whereas towards other children the tendency is to feel superior and bossy. These attitudes, however, can collapse in situations of frustration or criticism, revealing the underlying intense anxiety and hostility and giving rise to extremely violent behaviour (such as tantrums, cruelty to animals, faecal smearing, accusations of parental mistreatment, etc.—to quote only some of the reactions listed by Meltzer).

In adults, the pseudomature personality structure allows superficial adaptation and social success, but these, however, are accompanied by feelings of fraud ulence and inner loneliness. Meitzer points out how these typical character traits are reflected in the analysis of pseudomature patients. These patients tend to establish a positive idealized transference and a "pseudo-collaboration", in which the patient's aim is to gain approval and become the analyst's model patient. When this does not succeed the analyst is experienced as unable to understand the patient, or as envious, or as sadistic, and the transference relation is transformed into a negative or erotic one. In the countertransference, the analyst may feel like the parent of a model child (who needs to be admired for his adult behaviour, not criticized, etc.) and may easily take on the role of a parent (or analyst) who colludes with the idealization. In Meltzer's experience, with this sort of patient it is best not to interpret too soon, but to work on resolving the idealization of the self and the false independence by pointing out pseudomature behaviour and by helping the patient to make use of projection into the analytic breast to alleviate anxiety. In their dreams, these patients often represent food as idealized faeces, idealized toilet situations, intrusive or masturbatory situations, and so forth.

In a later paper (1982), Meltzer suggests the use of a terminology that unites Klein's and Bion's definitions with his own additions. It will be noted that the term "massive projective identification" is no longer used. Furthermore, it would seem that "intrusive identification" and the concept of "claustrum, used jointly, cover the concept of "projective identification with the internal object". The definitions of the terms used by Meltzer, and as followed throughout the rest of this book, can be summarized as follows:

- Projective identification is used in Bion's sense as an unconscious phantasy with the aim of communicating. It is the basic mechanism of learning from experience,

- Container: the inside of the object that receives and returns the projective identification.

- Intrusive identification is used in the Kleinian sense of defence mechanism and unconscious omnipotent phantasy. It consists in the pathological use of projective identification for invading an external object (Klein) or an internal object (Meltzer).

- Claustrum: the inside of the object penetrated into by intrusive identification.

D. Adhesive identification; projective identification in folie à deux

To complete our survey of projective identification in Meltzer's work, it is necessary to consider two further aspects: the first, adhesive identification, relates to the incapacity to use the mechanism of projective identification; the second, folie à deux, refers, on the contrary, to excessive and coinciding projective identifications in both directions (from subject to object and from object to subject).

In his book on autism (Meltzer et al., 1975), Meltzer takes up one of Esther Kick's (1968) concepts and discusses adhesive identification. He considers adhesive identification as the failure of projective identification, due to the primal incapacity of some children to make use of the containing function of the object. These children are unable to form the concept of an internal space in the object. They therefore identify with an object that has no "inside" (a bidimensional object), and they can only identify adhesively to its surface (see also chapter four, section A, herein).

In the case of folie à deux, the child projects into the mother, but the mother also projects into the child; these double projective identifications then tend to coincide and become confused, so that a situation arises in which it is no longer possible to distinguish what belongs to the one or to the other.

Adhesive identification and folie à deux are two specific pathological narcissistic features of identification. They must not be confused with what Meitzer, in his first writings, described as massive projective identification or with the other forms of projective identification referred to above.

CHART 1: Projection, projective identification, and projective identification with internal objects

E. Introjective identification

By intxojective identification, Meltzer (1978b) means the introjection of an object-relations experienc...