eBook - ePub

The Female Body

Inside And Outside

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Female Body

Inside And Outside

About this book

This book gathers together a number of cutting edge contributions about the female body, inside and out, from a large group of psychoanalysts who are at the forefront of new thinking about issues of femininity, the female body, sex and gender. It explores the female body in art, in pregnancy and motherhood, in sexuality and in the lifecycle, and finally the female body as scene of crime. As a result this book covers aspects of female creativity in its many aspects, both productive and generative and where there are difficulties or impediments. The psychoanalysts writing for this book have made an enormous contribution in the past and this book therefore aims to stimulate, challenge and provoke further discussion and new advances in this field.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Female Body by Ingrid Moeslein-Teising, Frances Thomson-Salo, Ingrid Moeslein-Teising,Frances Thomson-Salo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Female Body in Art

Chapter One

The female body in Western art: adoration, attraction and horror

Abstract

37,000 years of art history will be examined to observe the many ways women’s bodies have been experienced and portrayed in Western culture. Thoughts, feelings and fantasies about women, and especially the manner in which they are divided into absolutes and opposites (e.g. good or bad; weak or powerful, seductive or innocent) will be illustrated. Themes such as nudity, relationships, birth, and fertility will be explored. The art of Picasso, Matisse, pre-historic Egypt, Hellenistic, Roman, Medieval, Renaissance, and nineteenth and twentieth century Western European art will all be presented. Greek art uses images of females, such as Hera, Aphrodite, Athena, Demeter, Persephone and Medusa, in order to illustrate the ways women have been depicted in art for the past 2500 years. Psychoanalytic understanding of female psychology will be part of the discussion about the Greek goddesses. Idealized or ordinary depictions of women were created depending upon the civilization. The splitting of women into categories will be clearly depicted in images from more recent civilizations.

In this Chapter we are going on a journey through 37,000 years of art history to catch glimpses of the many different ways the female body has been experienced and portrayed in Western culture.1 The themes I shall use derive from what we, as psychoanalysts, know of the thoughts, feelings and fantasies about women that come from our patients (both male and female); and from the patients, who have been seen and heard over the last hundred years by our fellow professionals, including Freud himself.

The mind frequently functions in terms of absolutes and opposites, especially when we are very young and have immature cognitive and perceptual abilities. We shall repeatedly find that women are depicted as good or bad; weak or powerful; desirable or terrifying; bearers of life or harbingers of death; the font of nurture and intimacy, or the source of deprivation, separation and abandonment.

All these themes will be visible as we proceed through the history of Western art. Sometimes our subject will be the issue of nudity. Often it will be the relationships between the goddess and her peers, and/or the goddess and her audience. At times we will jump forward in time following a particular theme and its variations. The wide range in the way women’s bodies are depicted reflects the very sort of individual disparity that Chodorow (2010) urges us to recall. We also see how that variety alternates with some remarkably fixed ways of seeing.

Whilst there is much speculation about the earliest images of the female body, we know that in pre-historic times (40,000–10,000) there was an emphasis on the female figure. We also know that certain forms, namely roundness, budding, blossoming, were all equated with woman. Indeed in art-historical terms, anatomy was destiny. The most prominent anatomical features, breasts and big bellies, are seen in every cultural era and locale, from the earliest to the present. The Venus of Willendorf is a perfect example. (Figure 1)

Not surprisingly we find the mysterious subject of pregnancy and birth playing a dominant role in the art and architecture of earliest civilizations. The oldest known representation of the female form is the recently discovered Venus of Hohle Fels, a small ivory figurine with a loop on the top so that it could be worn as a pendant around the neck. (Figure 2). This “Venus” figurine has been dated to 35,000 BCE, and was unearthed in a cave in southwestern Germany. The bulbous shapes of “Venus” figurines found at other locales in Europe as well as in the Near East, with their hugely rounded breasts and bellies, carry the same message: they are fertility figures who imply the potential to be pregnant.

Figure 1. Venus of Willendorf (ca. 24,000–22,000 BCE).

It may not have been clear to Paleolithic cultures that intercourse was connected to pregnancy and birth, and that ignorance could have made women appear fantastically powerful as they seemed to magically bring forth children without the help of men. In prehistory, the connection between sex, subsequent pregnancy and birth would only have been observed in agricultural societies where animals were kept.

The earliest documented image of childbirth itself was found at the Neolithic site Catal Huyuk in Anatolia 8500–5500 BC. The image is of a woman giving birth seated on a birthing chair. Her pendulous breasts hang over her bulging belly, and, between her ankles, an infant’s head emerges. In prehistoric Malta, the female body illustrated fecundity in other ways; sacred buildings were created in the shape of a woman’s body. The large temples on the island of Gozo, Malta, whose entrances were obviously sacral spaces located at the vagina-like openings of the buildings, were constructed from 3600–3000 BCE, approximately one thousand years before the first Egyptian pyramid.

Figure 2. Venus of Hohle Fels (35,000 BCE).

Figure 3. Ggantija Temple in Xaghra (3600–3000 BCE).

Here is Ggantija (Giant Lady in Maltese) (Figure 3). We can only guess at the rituals and spiritual practices of the builders of such temples, but the shapes of the structures leave little doubt about the gender of the cult goddess for whom they were built. The numerous sculptures of bulging-bellied figurines that were discovered at the sites show the correlation of the sculpture to the architecture and the power the female body exerted on the artists and their audiences. Another Neolithic monument in Malta raises the subject of the link between birth and death—also understood as the link between the womb and the tomb. The Hypogeum (dating from 3600–3300 BCE) was an underground place of worship and a funerary crypt. It is an extraordinary large multilevel, hollowed-out architectural space with halls, chambers, and passages, in which were found rounded female figurines, human bones and various prehistoric artifacts.

While we do not have clear evidence of the links between birth and death in prehistory, we shall see that those themes are continuous in art and become more numerous over time, largely because the invisible inside of female bodies is both awe-inspiring and terrifying. In the sexual act it can provide release and pleasure and can also produce a phallus-like creature in the form of a human baby.

Attempts to draw a sweeping simple picture of earliest human activity, such as the idea of a pervasive goddess cult, have been dismissed as wishful hypotheses. Nevertheless, the preponderance of divine female figures and the nearly complete absence of male divinities strongly suggest that the earliest Mediterranean cultures, including Minoan and Cycladic, were matriarchal and matrilineal. They may have been part of a continuous network of diverse cultures, originating in and around the Mediterranean Sea, which worshipped an ancient mother goddess. As we proceed, we shall find traces of these ancient matriarchal cultures in the better-known and better-documented patriarchal cultures of Greece and Rome. Many, if not most, of the gods and goddess of those two cultures had double natures; either because the humans inventing them had recognized their own complex inner worlds, and/or because they were composites created in different regions at different periods of time.

Ancient Egypt

Egyptian culture was one of the longest lasting in the ancient world. While the dynastic realms began in 3200 BC and ended only when the Romans conquered Egypt in 31 BC, the predynastic period goes back almost two thousand years earlier. The fertile Nile valley and the relatively isolated situation of ancient Egyptian cities made this relatively stable 5000-year history possible.

The sculpted images of women with infants (from c.3000 BCE, the most ancient period of Egyptian art) are roughly in line with the prehistoric images of fertile females with large hips and bountiful breasts. Eventually a topos developed of the goddess Isis with her son Horus. The image of Isis seated with her suckling son, Horus, (Figure 4) would become the dominant way—if not almost the only way—in which women were depicted partially nude in Christian art. (Figure 5) Ennobled by maternity, mothers could be shown to have sexual characteristics as long as they were useful to the continuation of the human race and/or could recall for their observers the blissful moments of unity between mother and child. Here was an instance where the generalized image encouraged viewers—specifically young mothers—to identify with the loving care bestowed upon an infant and to recall the lost paradise of early merging (Baxandall, 1972).

Figure 4. Isis and Horus (ca. 600 BCE).

Egyptian art tended to change gradually, and there were established prototypes for the depiction of men and women, both separately and together, that codified the appreciation of female beauty and reflected the female status. Thus we find magnificent images of the wives of pharaohs dating back to the earliest dynasties and moving forward through Ptolemaic times. Women, like men, are usually depicted as they are meant

Figure 5. Nino Pisano: Madonna Nursing the Child (ca. 1350 CE).

to be in the afterlife—young, attractive and healthy, just as the actual bodies were embalmed to preserve their best bodily self. Without such images and preserved bodies, the soul and spirit of the deceased would not be able to continue his or her journey through everlasting life.

The earliest preserved records from the Old Kingdom onwards suggest that the formal legal status of Egyptian women was similar to that of Egyptian men. Women could acquire property in their own names and dispose of it as they wished, and they, like their husbands, could terminate a marriage. While Egyptian women had more power than did their later Greek counterparts, their social status was still restricted largely to the home and the activities associated with childrearing. A New Kingdom literary text clearly reflected this: “A woman is asked about her husband; a man is asked about his rank.” As for men, a Middle Kingdom text warned men: “Do not contend with your wife in court. Keep her from power, restrain her. Thus will you make her stay in your house”. (The Instructions of Ptah-Hotep, 3580 B.C.)

When presented as a sculpted couple, the aesthetic formula, which corresponded to the legal and social status of each, was fairly strict. Men were coloured red or reddish brown to indicate their experience as outdoor or worldly beings. Women, by contrast, were painted with lighter skin, as befitted their place inside the home and away from the searing sun.

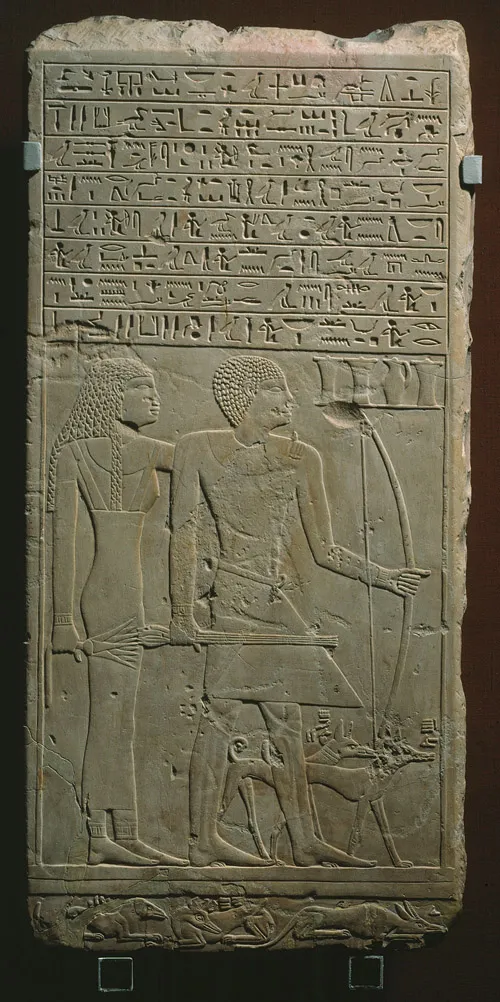

A seated figure of a man with his wife and son from Saqquara demonstrates another way that Egyptian artists could depict the differences between male and female, and adult and child. The father sits stolidly centred and is a large full-size figure. His wife and son, who are much smaller, are placed next to his feet and legs. The wife sweetly grasps her husband’s lower limbs; and the boy’s small standing body, like his mother’s upper torso, is nude.

Men wore kilts, usually white, leaving their upper bodies bare, while women wore long garments, also usually white, covering them from neck to mid lower leg. But the most striking difference between the sexes appears less in the garments they wear than in what the clothing tells us about the body—and the genitals—underneath. Unrevealing garments cover a man’s lower torso, such as the stiff triangular kilt of The Stele of Kai (Figure 6) which shows prototypical images of both a male and a female. With remarkable regularity, the phallus is symbolized as the

Figure 6. Stele of Kai (ca. 2000 BCE).

scabbard of a sword tucked in at the waist and aiming downwards, like a fold of fabric—or a long vertical belt or tassel hanging down from the centre of the kilt. For women, the clinging nature of their gossamer-thin garments leaves little doubt about their nudity or near nudity. In many cases, as in the Stele of Kai, the upper part of the woman’s dress is abbreviated to a strap, showing one or both of her breasts. The nipples are usually emphasized or visible.

What can we know about the unconscious of the artists and their audiences from past millennia? Just as we can hypothesize from typical behaviours that we observe in our patients, we can cautiously speculate about patterns we see in art history, particularly when those patterns are repeated over time. The repetitions suggest that the conventions must have been known to both the artists and their audiences. I feel on reasonably safe grounds in proposing that the males presented in Egyptian art needed to have a visible displaced-phallic symbolic element. Women on the other hand, needed to be tangibly appealing, inviting the viewer to imagine touching the rounded shapes so lovingly emphasized by the linear patterns of the nearly transparent garments.

Hatshepsut, the female pharaoh who reigned in the 18th Dynasty (1508–1458), (Figure 7) was famously depicted as both male and female. However strong a ruler a woman could be in actuality at the time, Hatshepsut still needed to have masculine attributes attached to her body to justify her masculine form of leadership. Thus, she is given a phallic beard in almost all sculpted depictions. Though her face is allowed its feminine shape, her breasts are invariably reduced to an androgynous near flatness. Daughter of a pharaoh, wife/sister of another and regent for her stepson, (yet another pharaoh) this powerful female led the kingdom for approximately twenty-two years.

Kubie (1974) wrote extensively about the drive to become both sexes, positing it as a universal phenomenon, though one that both sexes mostly deny. Direct observations of children and his vast psychoanalytic experience convinced Kubie (1974, pp. 355–6) that “the unconscious drive is not to give up the gender to which one was born but to supplement or complement it by developing another, side by side with it—the opposite gender, thereby ending up as both.” In our art historical tour we shall observe a fairly constant thread of androgynous imagery from anci...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ABOUT THE EDITORS AND CONTRIBUTORS

- SERIES EDITOR’S FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: THE FEMALE BODY IN ART

- PART II: PREGNANCY AND MOTHERHOOD

- PART III: THE BODY AS A SCENE OF CRIME

- PART IV: SEXUALITY AND THE FEMALE BODY IN THE LIFE CYCLE

- AFTERWORD

- INDEX