![]()

1

What Are the Possibilities?

Norman McLaren from the NFBC. (Courtesy of Evelyn Lambart, National Film Board of Canada, 1952.)

Creating Magic

Silent Films and Beyond

Stop Motion and Its Various Faces

Creating Magic

The history of these animation art forms has not changed since the first edition of this book. History is written in stone, depending a little on the perspective from which it is told, but the present and the future are always organic and fluid. It does not make sense to try to parse out individuals and examples of work that were not as significant as the examples cited in the previous volume, but there have been some significant iterations of these techniques in the last 5 years. I will be citing several of these new and individual approaches to demonstrate the infinite possibilities that continue to unfold in photographic frame-by-frame non-puppet stop motion.

Humans are social creatures that have an innate need to share experiences and stories. Ever since humankind started communicating, stories that are real and unreal have been shared around the communal circle. The tribe was gathered together and a tale was told that revealed information, lessons, provocative thought, and emotional empathy. Often the more fantastic the story the more entranced the audience became and the stronger the message. This might have been the job of the shaman or chief, but soon everyone had stories and experiences to relate. Eventually stories became enhanced from the oral tradition through props and other means of visual storytelling. In just over the last hundred years, filmmaking has become a powerful vehicle to relate stories and to capture an audience’s imagination. Sight and sound are our most primal senses and filmmaking taps into these receptors. Soon after its introduction, filmmaking started to expand its repertoire and the “fantastic” became a possibility in storytelling.

Single-frame filmmaking has been around as long as film itself. The idea of fooling or tricking the eye has always been fascinating to people and the manipulation of live-action filming was the origin of this technique. Imagine the early days of filmmaking when audiences were seeing projected images on a screen, images that appeared to be alive and real for the first time. That was magic in itself. When filmmakers became a bit more sophisticated by stopping the camera in midshoot, removing an object from in front of the camera, and then continuing to film, the results were genuinely magic. As film started to mature, artists and practitioners began to see the endless possibilities that this new medium offered. This stopping the motion of filming and adjusting images, cameras, and events was the predecessor to special effects and animation.

We are talking about stop-motion photography, which has evolved into many variations. The most common form of stop motion that is recognized today is model or puppet stop motion. This is when figurative models are fabricated and animated frame by frame to create a narrative or experimental approach. Examples of this form are seen in films and on television. Feature films like Jiri Trnka’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Nick Park and Peter Lord’s Chicken Run, and Coraline, directed by Henry Selick, all exemplify this popular approach to figurative puppet stop motion. Television has also laid claim to this form of animation with popular programs like Pingu, Gumby, the Rankin/Bass Christmas special Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, and Robot Chicken. These, among other titles in this genre, are well loved and are considered more in the realm of traditional stop-motion puppet animation. Robot Chicken, created by Seth Green and Matthew Senreich, occasionally uses existing objects or models, but the fabricators adapt these objects or models to work for animation so they are a crossbreed of puppet and non-puppet/object animation. The work of PES is also a great example of an artist who crosses the gap between puppet and non-puppet stop-motion work.

The nontraditional or alternative use of stop motion utilizes people, objects, various materials like sand, clay, and paper, and often a mixture of these and other elements as the objects to be animated. The most common of the nontraditional alternative stop-motion techniques is known as “pixilation.” This term is attributed to the Canadian animator Grant Munro, who worked at the National Film Board of Canada with Norman McLaren in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. Both McLaren and Munro were major contributors to this art form. In pixilation, usually a person is animated like a puppet or model. There is a limited amount of registration in this approach to stop motion so the result is a rather kinetic, bewitched, fragmentary movement that appears pixilated or broken up. It has nothing to do with the modern-day term related to low-resolution digital images. Time-lapse photography and “downshooting” (animation on a custom animation stand), also known as “multiplane animation,” are two other forms of nontraditional alternative stop-motion photographic animation. We will explore each of these approaches and more in the following chapters.

Silent Films and Beyond

This interest in the manipulation of filming and single-frame adjustment started as soon as film arrived on the scene in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Lumière brothers are considered to have been the first to successfully shoot and project films for audiences (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

Auguste and Louis Lumière, circa 1895. (From Auguste and Louis Lumière, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auguste_and_Louis_Lumi%C3%A8re.)

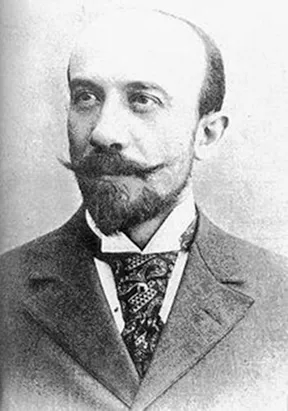

Their work was amazing to the French and, ultimately, international audiences of the late 1890s. Everyday scenes of that era are well recorded and documented in the factories and streets of Lyon, France. Once audiences became accustomed to the novelty of moving images, then the experimentation began. There were several artists who took the filmmaking technique much farther than Auguste and Louis Lumière, but the most significant artist was Georges Melies (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2

Georges Melies, circa 1890. (From Georges Méliès, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georges_M%C3%A9li%C3%A8s.)

The Parisian-born Melies was often referred to as the “cinemagician.” His work with film was influenced by his experience as a stage magician. Melies learned how to use multiple exposures, dissolves, time-lapse photography, editing techniques, and substitution photography where the camera was stopped and the subject was changed to create a magical effect. These silent films created in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century were like magic shows that featured special effects. This kind of filmmaking was the precursor to several different branches in the tree of stop motion, including modern-day special effects, puppet or model stop motion, and pixilation and its various forms. Melies’ The Conjuror, filmed in 1899, is a clear example of the relationship that he made between magic and his filmmaking (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3

The Conjuror, 1899. (From The Conjuror, 1899, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zs5BBaNJ6mg.)

In the film, he covers a woman with a cloth and pulls it off, revealing that the woman has disappeared and reappeared on an adjacent table. He then, through what appears to be magic, continuously switches positions with the woman using smoke and confetti to enhance the effect. This is most likely attained by editing the film and reenacting the action with different elements. The camera must be locked down in one position in order for this to work. The continuous movement of the actors helps create a smooth transition from one person or object to the next. The editing process was the first technique used in the manipulation of imagery, but before too long frame-by-frame manipulations shot in the camera became the most effective way to have ultimate control over the film’s outcome.

Another French contributor to stop motion and pixilation was Emil Cohl. His 1911 film Jobard ne peut pas voir les femmes travailler (Sucker Cannot See the Women Working) utilized real people and is one of the earliest pixilated films known. Unfortunately, many of Cohl’s films have been lost due to fire and neglect.

The Edison Company, founded by Thomas Edison, created some of the first motion pictures in the United States in his infamous Black Maria studio in West Orange, New Jersey, in 1893 (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4

Black Maria studio, circa 1893. (Courtesy of the Black Maria Film Festival, Jersey City, NJ.)

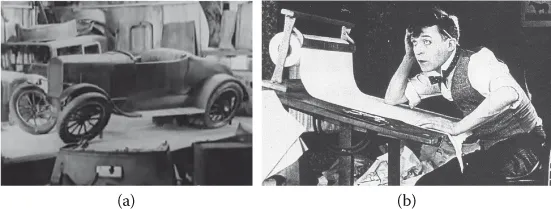

Similar to the Lumière brothers, Edison’s first films reflected everyday life and activities. Edison also attracted audiences and talent like the first established American stop-motion animators, James Blackton and Willis O’Brien. Both artists favored model or puppet animation. O’Brien produced special effects films like the 1915 The Dinosaur and the Missing Link: A Prehistoric Tragedy and the eventual 1933 King Kong. Artists were moving away from the obvious tricks of dissolves, position replacements, and editing techniques to techniques that were the beginnings of special effects and model animation. Pixilation took a back seat. Even artists like Charley Bowers favored models, as was illustrated in his 1930 film It’s a Bird, where Bowers has a bird eating metal materials and a car appears to be destroyed frame by frame as the film is run in reverse. This gives the appearance of the car assembling itself totally unassisted (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5

(a) Car assemblage from It’s a Bird by (b) Charley Bowers, circa 1935. ((a) From YouTube, It’s A Bird (1930), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z4I15-7L0ss; (b) from from Wikipedia, Charles_Bowers, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Bowers#/media/File:Charley_Bowers.webp.)

It is worth noting the Russian-born Polish animator Ladislas Starevich, who in 1910 was creating documentary films for the Museum of Natural History in Kovno, Lithuania. The final film in a series was focused on a fight between two stag beetles. Because these beetles would become dormant when the movie lights were on, Starevich decided to use dead beetles and, in place of their legs, to attach wire to their thoraxes with sealing wax. This innovat...