eBook - ePub

Narrative Approaches to Brain Injury

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Narrative Approaches to Brain Injury

About this book

This book brings together narrative approaches and brain injury rehabilitation, in a manner that fosters an understanding of the natural fit between the two. We live our lives by narratives and stories, and brain injury can affect those narratives at many levels, with far-reaching effects. Understanding held narratives is as important as understanding the functional profile of the injury. This book explores ways to create a space for personal stories to emerge and change, whilst balancing theory with practical application. Despite the emphasis of this book on the compatibility of narrative approaches to supporting people following brain injury, it also illustrates the potential for contributing to significant change in the current narratives of brain injury. This book takes a philosophically different approach to many current neuro-rehabilitation topics, and has the potential to make a big impact. It also challenges the reader to question their own position, but does so in an engaging manner which makes it difficult to put down.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Narrative Approaches to Brain Injury by David Todd, Stephen Weatherhead, David Todd,Stephen Weatherhead in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Understanding narratives: a beacon of hope or Pandora’s box?

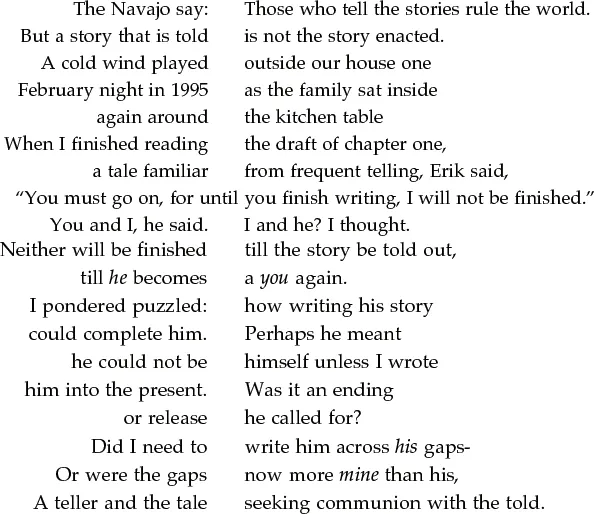

This chapter considers the use of narratives by people who have been affected by neurological illness and disability and, in particular, their naturally occurring, organic generation of narratives rather than those created as part of a therapeutic intervention. Much research has examined the content of people’s narratives, but little explores why people turn to narratives following brain injury and what impact such narratives might have for both readers and authors. Consider the following extract, for example, from Ruthann Knechel Johansen (2002), writing about her son, Erik, who survived a traumatic brain injury:

We begin our reflection on works such as the one above, by looking at the literature on writing narratives, before discussing the challenges generated by working with the existing literature. The chapter then goes on to consider the use and impact of reading narratives among a brain injury population, using primary empirical research. In presenting this research, we reflect on how narratives can support adjustment and recovery following acquired brain injury, while acknowledging that, for some, narratives might not be such a positive experience. Finally, the chapter considers the value of narratives for professionals and organisations that work with people affected by acquired brain injury. Much of this chapter is based upon the doctoral work of Ava Easton (Chief Executive of the Encephalitis Society) who co-authored the chapter with Karl Atkin (who holds a personal research chair at University of York).

When thinking about your own practice, can you identify positive instances of people telling the story of their illness experience. When have people struggled to tell their story? How would you explain the difference?

What does the literature tell us?

The concept of self and identity is one that endures through time. There are, however, certain conditions under which it might be disrupted and altered, brain injury being one such instance (Chamberlain, 2006; Fraas & Calvert, 2009; Lawton, 2003; Muenchberger, Kendall, & Neal, 2008; Nochi, 2000; Segal, 2010). Writing narratives following traumatic circumstances is not uncommon and might help people come to terms with what has happened to them, contributing in some way towards acceptance of living a life under what the German physician, Rudolf Virchow calls “altered circumstances” (Bell, 2000; Gerhardt, 1989; Hydén, 1997; Teske, 2006; Whitehead, 2006). Our self-identity is created partly through our on-going narration (Bruner, 2002; Harrison, 2008; Murray, 1999; Teske, 2006). Narratives enable us to present our view or experience of the world, in a way that we have some control over, although often with the hope that our accounts will find validation through our interactions with others (see Bourdieu, 1990). Narratives, therefore, express how we see ourselves and how we present ourselves to others. They are personal creations that exist and assume meaning within a social context.

Given this, one might expect a substantive literature on the impact or influence writing narratives has on those who read and write them. There is, however, a specific dearth of literature considering their impact among those affected by neuro-illness or disability, other than those generated in rehabilitation or therapeutic settings. Further, and historically, researchers have also tended to focus on the content of narratives rather than their social meaning and use (Riessmann, 2004). Consequently we know little about the motivations and outcomes for readers and authors (Alcauskas & Charon, 2008) and Medved (2007) states “What is missing from the literature is research on narratives from individuals who have been abruptly left with cognitive impairments” (p. 605). The lack of specific literature around acute and critical illness is also described by Rier (2000) and Lawton (2003).

What do you think are the reasons for the lack of literature on the motivations for, and impact of, narratives upon authors and readers?

Unlike their instrumental narrative use in rehabilitation settings, often with therapeutic goals in mind, many narratives are, for the most part, written for less obvious purposes. Understanding the value of narratives from the point of view of those who produce them provides an important addition to more traditional psychosocial research and helps to facilitate a more rounded and nuanced insight into people’s experiences. Bio-medicine has sometimes struggled with such approaches (Kreiswirth, 2000; Smith & Squire, 2007). Lorenz (2010, p. 163) recounts a conversation with a director of research at a renowned rehabilitation hospital in the USA. Lorenz asked if he had room on his staff for a qualitative researcher. The director responded by saying qualitative research with brain injury survivors was pointless because “… you just keep hearing the same story over again …”. Some authors also suggest that the contributions of people with neuro-disabilities are often not considered reliable, valuable, or important (Cloute, Mitchell, & Yates, 2008; Lorenz, 2010; Segal, 2010). Research suggests those affected worry that their narratives are not taken as seriously as they should be by others. Their authenticity (and value) is, in effect, questioned. Patients certainly feel this, and various accounts suggest their experience is not afforded due respect and, in turn, they are left feeling “fraudulent” (Easton, 2012). A sense of not being believed may have a particular impact on a population whose “broken brains” and cognitive difficulties are already invisible (Atkin, Stapley, & Easton, 2010). In addition, there is evidence of reluctance among researchers to interview and engage with people who have complex disabilities, such as cognitive problems or speech impairments (Lawton, 2003; Paterson & Scott-Findlay, 2002; Thorne et al., 2002). Such barriers go some way in explaining the lack of literature in both brain injury and in exploring the impact of narratives among those who read and write them.

Writing narratives: motivations, intentions, and impact

The prospect of why and when people write narratives as opposed to why they read them seems to offer a more tangible subject for evaluation. The use of narratives as a primary resource for creating meaning and purpose, along with their capacity to bring structure to complex and unexpected events, is discussed at length in the literature (Bruner, 2002; Jones & Turkstra, 2011; Riessman, 2004; Skultans, 2000; Teske, 2006). The role of narratives in framing “… the exceptional and the unusual into a comprehensible form” is also reinforced by Bruner (1990, p. 47), and that our motivation to write stories comes from a desire to understand the world around us, particularly when that world takes an unpleasant or unexpected turn (Riessman, 1990; Aronson, 2000; Bruner, 2002; Teske, 2006). Therefore, it is easy to appreciate how narratives enable people to document how their illness has had an impact upon their lives and often the lives of those closest to them, facilitating opportunities to reconcile and come to terms with what they have experienced (Harrington, 2005; O’Brien & Clark, 2006). Autobiographical accounts following neurological disease or injury (neuro-narratives) provide a particularly rich source of material.

In the same way that adjustment following neuro-disability is constantly changing, so, too, are people’s narratives (Segal, 2010). Narratives, although created at a single point in time, like time itself do not remain fixed, but can represent a reference point around which to make sense of experience (Harrison, 2008; Hovey & Paul, 2007). Our stories and how we choose to present them can be complex. They might not always be chronologically sequential; we reflect and revise our stories, particularly in response to those of others, and one person’s experience and interpretation of an event might differ greatly from another. People also choose what aspects of their “selves” and their experiences they choose to share, and those they wish to conceal (Harrison, 2008). It is the process of reinterpretation that occurs within these constantly changing circumstances that help us make sense of our experiences, and come to terms with what might be a very different sense of self, following neuro-illness or disability. Narratives are not only personal creations, either, but are simultaneously constructed from our social experiences, realised in our social environments, through interaction with others. Consequently, they attract social meanings, which can differ according to the perspectives of both the story-giver and the receiver (Bruner, 1994; Jenkins, 2006). Reconciling the personal and the social are at the heart of understanding their meaning, as an individual exercises and realises active agency, which is defined and reached through the processes of social negotiation (see Bourdieu, 1990).

Consider an event in your life which had a significant impact on how you saw yourself. What was your story of this event? How important was it to you to tell your story? Did others’ responses change the way you told the story? Did you tell the story differently according to who you were talking to? Did your story change over time?

Making sense of individual experience

Dealing with, or making sense of, one’s experience is a recurring theme in the literature, with many authors identifying this as having a significant role in why people write their narratives (Aronson, 2000; Bruner, 2002; Charon, 2001; Jones & Turkstra, 2011; Lillrank, 2003; Medved, 2007; O’Brien & Clark, 2006; Pinhasi-Vittorio, 2008; White-head, 2006). This suggests that people’s stories are less about solving their problems or finding solutions but more about their process: the journey as opposed to the destination (Bruner, 2002). According to Arthur Frank (1995), these are known more as quest narratives. In some cases, writing was an attempt to reconcile their current feelings of alienation and estrangement when people compared themselves to the way they were before their brain injury. Nowhere is this more clearly illustrated than by Luria (1987). The Man with a Shattered World is one of the most famous neuro-narratives of the twentieth century and provides an excellent example of a documentary narrative being used to create structure and coherence for experiences which are seen as outside the control of the individual. In a more recent account, Pinhasi-Vittorio (2008) introduced Ned, whose poetry enabled him to express himself and restore his self image; writing his poetry enabled him to organise his thoughts, reflect on them, and, through this process, a “new” Ned began to emerge.

The process of telling one’s story can be a cathartic experience (Aronson, 2000; Robinson, 2000). The process of writing and publishing provides validation and, in some instances, can be a request for understanding and support from others (Frank, 1997; Hydén, 1997; Murray, 2000; Skultans, 2000). We are, by nature, collective beings and the groups we belong to shape our identity. Groups can also provide us with stability, meaning, and direction (Haslam, Jetten, Postmes, & Haslam, 2009; Jones & Turkstra, 2011). Following a serious traumatic brain injury, Linge (1997) recalls that during his journey of recovery, his story appeared in several different publications during the 1980s, resulting in many letters and calls which he felt reduced his sense of isolation and fostered a new found sense of hope. With hope there comes the possibility of a future, and so the process of looking forward and not back is an important stage in people’s recovery (see Smith & Sparkes, 2005; Whitehead, 2006).

In making sense of one’s experience, there comes an opportunity to turn the “negative” into a “positive” (Fraas & Calvert, 2009; Kemp, 2000; Noble, 2005); this is what Arthur Frank (1995) calls a “restitution narrative”. The desire to positively reframe is evident in the online diary of Ivan Noble, which reached international audiences through the BBC News website (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/4211475. stm, accessed 23 April 2010). Ivan, suffering from a malignant brain tumour, describes “an urge to keep going and to try to make something good come out of something bad” (Noble, 2005). Similarly, following his operation to remove a brain tumour, Martin Kemp (2000) described writing his book as a way of remembering and replacing the bad with the good times. It is, perhaps, the process of writing which creates an opportunity to reframe one’s experience. It appears to be a strategy and an outcome that, although used therapeutically, also occurs naturally and indirectly as a direct result of writing and reflection.

The collective use of narrati...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- About the Editors and Contributors

- Series Editors’ Foreword

- Glossary

- Introduction

- Chapter One Understanding narratives: a beacon of hope or Pandora’s box?

- Chapter Two Brain injury narratives: an undercurrent into the rest of your life

- Chapter Three Narrative approaches to goal setting

- Chapter Four Narrative therapy and trauma

- Chapter Five Exploring discourses of caring: Trish and the impossible agenda

- Chapter Six Narrative practice in the context of communication disability: a question of accessibility

- Chapter Seven Helping children create positive stories about a parent’s brain injury

- Chapter Eight Using narrative ideas and practices in indirect work with services and professionals

- Chapter Nine Outcome evidence

- Index