![]()

1

Teacher Education: a Problematic Enterprise

Fred Korthagen

A teacher educator: “I really don’t understand why my student teachers don’t use the theory I taught to them. I see them have problems with their classes which could easily be avoided if only they would apply the content of my course!”

This introductory chapter describes the present problematic situation in teacher education, which can be characterized by a gap between theory and practice. This problem is analyzed by looking more closely at current practices in teacher education and the assumptions embedded therein. This chapter also prepares the reader for the chapters to come by presenting the basic ideas underlying an alternative approach to teacher education. Finally, an overview of the other chapters is presented.

1.1. INTRODUCTION

It is interesting to look back on the history of teacher education in order to see how, during the last part of the second millennium, basic ideas evolved about the way teachers should be prepared for their profession. It may help us to become aware that some assumptions have become so common that they are seldom discussed. First, three assumptions concerning the pedagogy of teacher education and the nature of teacher knowledge are discussed. Many research findings show that these assumptions create a gap between theory and practice. The chapter then focuses on this gap and the difficulty teacher educators face when trying to change teacher education practices. A new approach to teacher education is introduced, based on recent insights into the relation between teacher cognition and teacher behavior. The basic ideas underpinning this realistic approach are sketched. Section 1.9 presents an overview of the rest of the book.

1.2. THE HISTORY OF TEACHER PREPARATION

Let us start by looking at the period before formal teacher education started. By the end of the 19th century, teaching skills were mastered mainly through practical experience, without any specific training. Often a new teacher learned the tricks of the trade, after a study of the relevant subject matter, while acting as an apprentice to an experienced teacher.

During the late 19th and early 20th century, as psychological and pedagogical knowledge developed, academics wished to offer this knowledge to teachers in order to change education and “adapt” it to scientific insights. This is how the idea of the professionalization of teachers began. Indeed, as Hoyle and John (1995) point out, the availability of a recognized body of knowledge is one of the most important criteria for categorizing an occupational group as “professional” (see also McCullough, 1987).

During the second half of the 20th century, this wish to equip teachers with a professional knowledge base was stimulated by a growing desire, worldwide, to educate a broader group than the most gifted children. This democratization of education spurred on the wish for educational change, and especially to train a larger number of prospective teachers and to provide them with the necessary professional knowledge.

The general trend was to teach teachers courses in relevant knowledge domains, for example the psychology of learning. Gradually, however, it became clear that teachers did not carry much of this knowledge base into practice and more was needed. The knowledge base should become visible in the skills that teachers used in the classroom. This led to the introduction of competency-based teacher education (CBTE). The idea underlying CBTE was the formulation of concrete and observable criteria for good teaching, which could serve as a basis for the training of teachers. For some time, process–product research studies, in which relations were analyzed between concrete teacher behavior and learning outcomes of students, were considered a way to nurture this approach to teacher education. From this research, long lists of trainable skills were derived and became the basis for teacher education programs.

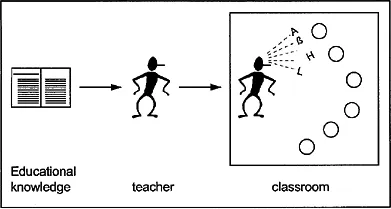

Behind this line of thought one can see what Clandinin (1995) calls “the sacred theory-practice story”: teacher education conceived as the translation to practice of theory on good teaching. The desire to use as much of the available knowledge as possible has led to a conception of teacher education as a system in which experts, preferably working within universities, teach this knowledge to prospective teachers. In the best case, they also try to stimulate the transfer of this knowledge to the classroom, by skills training (which is certainly a strong characteristic of CBTE) or by assignments to be carried out during field experiences (see Fig. 1.1).

This is what Carlson (1999) calls the “theory-to-practice” approach. Wideen, Mayer-Smith, and Moon (1998, p. 167) put it like this:

In addition, Barone, Berliner, Blanchard, Casanova, and McGowan (1996) state that many teacher programs consist of a collection of separated courses in which theory is presented without much connection to practice. Ben-Peretz (1995, p. 546) says:

Schön (1983, p. 21) speaks about the technical-rationality model, which is based on the notion that “professional activity consists in instrumental problem solving made rigorous by the application of scientific theory and technique.” In fact, three basic assumptions are hidden in this view (cf. Hoyle, 1980):

1. Theories help teachers to perform better in their profession.

2. These theories must be based on scientific research.

3. Teacher educators should make a choice concerning the theories to be included in teacher education programs.

The technical-rationality model has been dominant for many decades. In fact its dominance seems to become even stronger (Imig & Switzer, 1996, p. 223; Sprinthall, Reiman, & Thies-Sprinthall, 1996), although many studies have shown its failure in strongly influencing the practices of the graduates of teacher education programs. I look more closely at this problem in the next section.

1.3. PROBLEMS RELATED TO THE TRADITIONAL APPROACH TO TEACHER EDUCATION

Many researchers showed that the traditional technical-rationality paradigm does not function well. Zeichner and Tabachnick (1981), for example, showed that many notions and educational conceptions, developed during preservice teacher education, were “washed out” during field experiences. Comparable findings were reported by Cole and J. G. Knowles (1993) and Veenman (1984), who also points toward the severe problems teachers experience once they have left preservice teacher education. Lortie (1975) presents another early study of the socialization process of teachers showing the dominant role of practice in shaping teacher development.

In their well-known overview of the literature on teacher socialization, Zeichner and Gore (1990) state that researchers differ in the degree to which they consider teacher socialization as a passive or an active process. In the so-called functionalist paradigm, the emphasis is on the passive reproduction of established patterns, thus creating continuity (see, e.g., Hoy & Rees, 1977). Zeichner and Gore view Lacey’s (1977) study of teacher socialization in the United Kingdom as an example of the interpretative paradigm, as it is “aimed at developing a model of the socialization process that would encompass the possibility of autonomous action by individuals and therefore the possibility of social change emanating from the choices and strategies adopted by individuals” (Zeichner & Gore, 1990, p. 330). This emphasis on the in-dividual’s choices and possibilities to change educational patterns is even stronger in the third paradigm distinguished by Zeichner and Gore, the critical approach (see, e.g., Ginsburg, 1988). The central purpose of critical approaches is “to bring to consciousness the ability to criticize what is taken for granted about everyday life” (Zeichner & Gore, 1990, p. 331). It will be clear that studies located within the second and third paradigm are more focused on the innovative possibilities of new educational insights brought to the schools by novice teachers. However, all studies on teacher development emphasize that it is very difficult for an individual to really influence established patterns in schools. Educational change appears to be a beautiful ideal of teacher educators, but generally not much more than an ideal. Bullough (1989) emphasizes that, in this respect, we are dealing with a severe problem in teacher education. As Zeichner and Gore (1990, p. 343) put it:

It is interesting to note that this problem is found in many different countries. For example, at Konstanz University in Germany, large-scale research has been carried out into the phenomenon of the “transition shock” (Dann, Cloetta, Müller-Fohrbordt, & Helmreich, 1978; Dann, Müller-Fohrbrodt, & Cloetta, 1981; Hinsch, 1979; Müller-Fohrbrodt, Cloetta, & Dann, 1978), which regrettably went largely unnoticed by the English-speaking research community. It showed that teachers pass through a distinct attitude shift during their first year of teaching, in general creating an adjustment to current practices in the schools, and not to recent scientific insights into learning and teaching. Building on the work of the Konstanz research group, Brouwer (1989) did an extensive quantitative and qualitative study in the Netherlands among 357 student teachers, 128 cooperating teachers, and 31 teacher educators, also showing the dominant influence of the school on teacher development. He found that an important factor promoting transfer from teacher education to practice was the extent to which the teacher education curriculum had an integrative design, or in other words, the degree to which there was an alternation and integration of theory and practice within the program. This important issue will be elaborated on in chapter 3, together with the causes of the failure of the technical-rationality approach.

Apart from the fact that studies into teacher development and teacher socialization show that the classical technical-rationality approach to teacher education creates little transfer from theory to practice, this approach creates another fundamental problem. Elliot (1991) states that teachers who realize they are unable to use the theory presented to them by experts often feel they fall short of living up to the expectations these experts seem to have of their capabilities. Elliot (1991, p. 45) says that “teachers often feel threatened by theory” and these feelings are enhanced by the generalized form in which experts tend to formulate their knowledge and by the ideal views of society or individuals behind their claims. As such, the technical-rationality approach implies a threat to teachers’ professional status.

Indeed, what do we see happen in teacher education? Even if student teachers rationally understand the importance of theory as a means to support practice, they soon experience that they are not the only ones struggling so much with everyday problems in their classrooms that the whole idea of applying theory becomes an impossible mission. They see the same phenomenon everywhere around them in their practice schools. The only way out of the feeling of always falling short is to adapt to the common habit of teachers to consider teacher education too theoretical and useless. Then they can no longer be blamed for not functioning according to the theoretical insights; but teacher education can be blamed. It will be clear that this social game of ...