![]()

1

THE INTERNATIONAL DIVERSITY OF STUDENT ENGAGEMENT

Masahiro Tanaka

UNIVERSITY OF TSUKUBA

Introduction

The term ‘student engagement’ has become commonplace in global writings on higher education (Millard et al., 2013). However, the meanings of this term are actually quite diverse. One of the reasons for this diversity is that the specific who, what, where, when, how (to implement), and why (in pursuit of what objectives) of student engagement differ significantly across countries. In Sweden and Finland, for example, importance is placed on the work of student representatives elected by the student council. The representatives coordinate with operational partners and teaching staff for the continuous improvement, evaluation, and support of education through participation in committees related to educational operations. In the United States, in contrast, emphasis is placed on regular student surveys to obtain an understanding of the degree of student participation in student life as a whole. Notwithstanding such clear differences, both types of engagement can be categorised as ‘student engagement’.

At the same time, global similarities can be discerned in the motivations behind the promotion of student engagement. These similarities lie in the shared recognition of the need to draw on student perspectives in educational enhancement. The system or form of student engagement then differs according to whether the methods for gaining an accurate understanding of such perspectives are direct (personal exchange of perspectives between students and instructors) or indirect (aggregation of perspectives through questionnaire surveys). This book offers expert analyses of the methods of a variety of countries: Australia, Brazil, China, Finland, Japan, Kazakhstan, Mozambique, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The experts who author the chapters in this volume are Stuart Brand and Luke Millard (Birmingham City University, UK), Peter Felten (Elon University, USA), Åsa Kettis (Uppsala University, Sweden), Kuanysh Tastanbekova (University of Tsukuba, Japan), Bernardo Sfredo Miorando (Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil), Ryan Naylor (La Trobe University, Australia), Jani Ursin (University of Jyväskylä, Finland), Reiko Yamada (Doshisha University, Japan), Tong Yang (Southeast University, China), Nelson Casimiro Zavale and Patrício V. Langa (Eduardo Mondlane University, Mozambique) and the author of this chapter, Masahiro Tanaka (University of Tsukuba, Japan). While their analyses will form the contents of Chapter 2 onwards, this chapter will focus on presenting an overview of the existing literature on student engagement and drawing on the literature to develop a clearer definition of the concept.

Existing literature and the definition of student engagement

The research of George Kuh, who developed the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), is well known throughout the world in the field of student engagement (Kuh, 2001). This study can be considered to be the defining text emerging from the college impact research conducted mainly in the United States since the 1960s. Kuh was strongly influenced by three research outputs.

The first research output that influenced Kuh was the analyses of Nevitt Sanford. Sanford’s research showed that student growth is greatly influenced by the inclusion of extracurricular activities within the learning environment of the university (Sanford, 1962). On this basis, there are many questions in the NSSE that focus on the level of satisfaction with the learning environment. The second output that Kuh drew on was Alexander Astin’s Student Development Theory (Astin, 1984), which states that the deeper students become involved in their learning, the better their learning outcomes will be. He later proposed the I-E-O (Input-Environment-Outcomes) model and demonstrated the utility of comprehensively investigating student engagement levels (Astin, 1991). Based on these studies, the NSSE questionnaire items cover a range of holistic topics. The third influential research output was Arthur Chickering and Zelda Gamson’s seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education that they presented to university teaching staff (Chickering and Gamson, 1987). The NSSE was designed to measure the levels of adherence to these principles.

According to Kuh’s definition of the development of the NSSE, ‘Student engagement represents (1) the time and effort students devote to activities that are empirically linked to desired outcomes of college and (2) what institutions do to induce students to participate in these activities’ (2009: 683, emphasis by Kuh, but numbers in parentheses are added by the author of this chapter). The interesting aspect of this definition is that (2) shows that it is the responsibility of the university to guarantee the amount and quality of (1). Conversely, there are no duties required of or responsibilities placed upon the student.

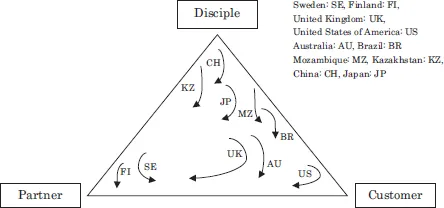

Should the practice of student engagement be the obligation of the student, the university, or both parties? This question may be very important in developing an understanding of student engagement. In this context, it can be proposed that the locus of responsibility for student engagement differs according to whether the student is positioned as disciple, customer, or partner, as shown in Figure 1.1.

FIGURE 1.1 Views of students and positioning of responsibility for student engagement

Note: the arrows in Figure 1.1 describe positions of the ten countries examined in this book. These positions will be tested in the final chapter of the book through analysis of the countries.

The perspective that views students as disciples is one that has long been upheld in higher education institutions since the establishment of Humboldt University in Berlin. In universities that maintain the Humboldt philosophy, the right of instructors to freely impart the results of their own research (academic freedom) is guaranteed (Tanaka, 2005). In such an environment, instructors need not take an interest in the curriculum as a whole and sometimes may not even question their own educational methods, while actions by students to improve educational methods are considered the height of rudeness. In such a situation, it is difficult to maintain the view that promotion of student engagement is the responsibility of the university. Furthermore, it is unlikely that students will be given the right to participate in attempts to improve their education.

A perspective that views students as customers has been proposed in a number of countries, including the United States: in that case, the commercialisation of higher education has become highly advanced through the introduction of and increases in tuition fees due to decreases in public funding. According to Maringe:

HE became a tradable service, based on demand and supply laws under which students became key consumers while universities and their staff were the providers. Consumerism is the central tenet of the free market in which business success depends almost entirely on satisfying customer needs and exceeding their expectations. (2011: 142)

In sum, universities that cannot provide education to the satisfaction of students will lose students and eventually go bankrupt in a competitive environment. Accordingly, it can be said that the promotion of student engagement for the purpose of gaining accurate knowledge of student demands and expectations is the obligation of the university, as its survival may depend upon it. Note, however, that the student has no duty to provide such information.

The perspective that positions students as partners took root relatively early in countries such as those of Northern Europe: here, the law establishes the principle of tripartite governance, comprising teachers, administrators, and students. At present, this viewpoint has gained political support, primarily in European countries, with the advocacy of steps such as the inclusion of students in the Bologna Process (Levy et al., 2011). When students are positioned as partners of the instructors, they acquire the right to participate in the decision-making processes of the university but at the same time become duty bound to cooperate in the support, evaluation, and enhancement of education and to shoulder a collective responsibility with respect to the outcomes of such processes. Regarding this responsibility, Cook-Sather et al. comment:

student-faculty partnerships rooted in the principles of respect, reciprocity, and responsibility are most powerful and efficacious. Each of these principles is foundational to genuine relationships of any kind, and each is particularly important in working within and, in some cases, against the traditional roles students and faculty are expected to assume in higher education. All three of them require and inspire trust, attention, and responsiveness. (2014: 2)

As noted by Cook-Sather et al., instructor respect (and, implicitly, trust) for students is essential for building a mutually beneficial relationship in the context of educational enhancement. Students should, however, be treated as adults in the midst of a process of growth, meaning that there are some limits to the degree to which they can be trusted to deal with operational tasks. This book utilises multiple country-level analyses to discuss this aspect.

In addition to identifying the responsibility for student engagement, the investigation into the objectives of student engagement is also essential for developing a clearer understanding of the concept. This book will conduct this investigation by examining student engagement through the lens of the following three levels posited by Healey et al. (2010: 22):

- Micro: engagement in their own learning and that of other students

- Meso: engagement in quality assurance and enhancement processes

- Macro: engagement in strategy development

The core objective of micro-level student engagement is the improvement of learning experiences and outcomes for the individual student. In the words of Coates (2006: 26), ‘learning is influenced by how an individual participates in educationally purposeful activities’. Furthermore, if activities that support the learning of fellow students (peer support) are included in micro-level student engagement, then the improvement of learning outcomes for others can also be considered to be a main objective.

Meso-level student engagement is the main theme of this book. The primary objective of student engagement in this level is the inclusion of the voice of the students in educational evaluation and enhancement. As noted above, there are direct (the personal exchange of perspectives between students and instructors) and indirect (aggregating perspectives through questionnaire surveys) ways to collect student experiences and perspectives. The results of the NSSE, which can be regarded as an indirect method, for example, can be used to clarify the current student situation and as evidence of educational enhancement. The reason for this, as pointed out by Pascarella et al. (2010: 21) is that ‘the NSSE results regarding educational practices and student experiences are good proxy measures for growth in important educational outcomes such as critical thinking, moral reasoning, intercultural effectiveness, personal well-being, and a positive orientation toward literacy activities’.

In broad terms, there are two types of direct method – participation in external quality assurance and participation in internal quality assurance. The former refers to students carrying out some kind of evaluation activity as employees of a third-party evaluation organisation such as an accreditation body (for example, participation as a member of an evaluation group that visits an institution undergoing an accreditation audit). The latter can be assumed to refer to activities such as (1) the creation of ‘student reports’ to be submitted to external evaluation bodies, (2) participation in interviews with such bodies, and/or (3) participation by a student as an official member of an internal quality assurance organisation of the university.

It should be clarified that, in higher education, quality assurance (QA) is not the same as quality enhancement (QE), although these are seen as a continuum. According to Elassy (2015: 259):

whereas QA focusses more on assessing the quality to determine the limitations and the strengths of HEIs, it could also be understood as a diagnostic process in an institution. QE is concerned more with improving the quality as a curing process of the limitations that might be found when the quality was assured, and at the same time, develop the strengths in HEI, if there is any.

The macro-level objective of student engagement lies in the reflection of university operations in benefits for students. Note, however, that in cases where the interests of students and the university are in conflict, dialogue between both parties is essential in order to elucidate common ground. Further, consideration must be given to benefits not only for students and the university but also to benefits for society as a whole. Moreover, the involvement of students in the management of the university can be regarded as having the effect of increasing the transparency of the university’s decision-making process (Lizzio and Wilson, 2009).

In light of the above, the following considers the definitions of student engagement offered in the existing literature. Based on Kuh’s definition discussed above, Trowler sets out his own definition as follows:

Student engagement is concerned with the interaction between the time, effort and other relevant resources inves...