![]() I

I

How Has the Availability, Content, and Stability of the Jobs Available for the Working Poor Changed in Recent Decades?![]()

1

The Low-Wage Labor Market: Trends and Policy Implications

Jared Bernstein

Economic Policy Institute

Introduction

This chapter attempts to do two things. First, there is an empirical examination of the low-wage labor market, past, present, and future, using a set of descriptive tables and figures. Second, I ruminate about the role of low-wage work in our economy, arguing that for both political and economic reasons it plays an integral role in our society. For this reason, through booms and busts, low-wage employment, along with working poverty, will continue to play a significant role in our labor market, a view supported by recent Bureau of Labor Statistics occupational projections through 2010. The conclusion introduces some policy recommendations targeted at the gap between the earnings of low-wage workers and the economic/social needs of their families.

The empirical part of the chapter needs little introduction. It includes a fairly extensive set of tabulations designed to shed some light on the characteristics of low-wage workers and their jobs. Data permitting, I introduce some historical perspective, particularly regarding the extent of low-wage work, wages, and, to a lesser extent, compensation. To gain some insights about future trends in low-wage work, the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) occupational projections of job growth over the next decade are presented and discussed.

The less empirical part of the chapter is a broad discussion of the role of low-wage work in our economy and our society. The goal is partially to gain a better understanding of the context of low-wage work in America. But beyond that, better understanding of context will hopefully lead to a more appropriate set of policies designed to address the problem of working poverty.

The line of reasoning regarding these issues is as follows. Relative to most other industrialized economies, we create a large share of low-wage jobs provide little protection from the vicissitudes of the market. This has always been the case here, but is more so now, post-welfare reform, when historically large numbers of working parents are more dependent on earnings than at any time in the past 30–40 years. A particularly dramatic finding in this regard is that twenty years ago, the income of low-income mother-only families was comprised of about 40% earnings and 40% public assistance. In 2000, those shares were 10% cash assistance (including the value of food stamps) and 73% earnings (including the value of the Earned Income Tax Credit).

At the same time, we pride ourselves on the number of jobs we create and our low unemployment and inflation rates relative to other industrialized (e.g., European) economies. We also, as a society, tend to be very suspicious of market interventions that block the path of the “invisible hand.” In addition, we’re very cost conscious—when a program is introduced to raise the quality (i.e., stability, compensation, etc.) of low-wage jobs, its potential impact on prices is often major political stumbling block.

These realizations lead us to the following contention: our large and growing low-wage labor market is an integral part of our macroeconomy and our lives. More than any other country, we depend on low-wage, low-productivity services to sustain our life styles. The impact of this reality, to put it in a somewhat reductionist manner, is that an inequality-generating structure has evolved in our economy/labor market of which low-wage service employment is an integral component. These jobs serve to reduce unemployment and raise employment rates, hold down prices, and serve an increasingly bifurcated (by income/class) society.

What are the implications and consequences of this? First, we should be clear that the low-wage labor market is alive and growing and is embedded in economic lives. Despite popular rhetoric to the contrary, this is not a nation computer analysts. At the same time, there is no reason why the living standards of low-wage workers should not rise as the economy grows. As shown below, the full-employment economy of the latter 1990s had a very significant and positive impact on the wages, compensation, and incomes of low-income working families. Even in this context, however, the incomes of many low-income families fell below a level that would reliably enable them to meet their basic consumption needs. Even in the best of times, we still need to be certain that a coherent and accessible set of work-related supports is in place to close the gap between earnings in this sector and the consumption needs of families who work there.

Part I: The Low-Wage Labor Market, Past, Present, and Future

There are, of course, numerous ways to define the low-wage labor market. A few decades ago, a theoretical framework for viewing the low-wage labor market was articulated by political economists. Their discussions of “segmented labor markets” still provide a useful framework through which to view the problem (see Bernstein & Hartmann, 1999). This research, associated with Harrison, David Gordon, Piore, and others, argues that jobs are “organized into two institutionally technologically disparate segments, with the property that labor mobility tends to be greater within than between segments” (Harrison & Sum, 1979, p. 88). Core jobs, those in the primary segment, pay higher wages and are more likely to provide fringe benefits (such as health insurance and paid vacations). Jobs in this segment also have ladders upward (often within the firm, called “internal labor markets”), whereby workers can improve their earnings and living standards over time.1

Conversely, jobs in the secondary segment tend to lack upward mobility. They pay lower wages, offer fewer benefits, tend to be non-union, and generally offer worse working conditions than primary-sector jobs. They are also less stable than core jobs, leading to higher levels of job turnover and churning in this sector Race and gender based discrimination are more common here than in the primary segment.

Today’s literature is much less theoretical and tends to draw on large microdata sets to examine the employment, earnings, and characteristics of those earning low wages. An important distinction here is in regard to the sample of interest: are we interested in all low-wage workers regardless of family income or are we only interested in the low earnings of workers in low-income families? Examining the overall sample of low-wage workers is the best way to learn about the structure of low-wage labor: what types of jobs are there, what do they pay, both in terms of wages and fringes, who holds them, what determines their growth or diminution? The other group, a sub-sample of the first, is conditioned on income and focuses more on the living standards of low-income working families, a group that has much currency in discussions of welfare reform and working poverty.

The distinctions are useful from a policy perspective. Policies such as Earned Income Tax Credit, a wage subsidy targeted at low-income working families, are wholly focused on the subset conditioned on income. Such policies do not aim to lift the living standards of low-wage workers in higher-income families. On the other hand, policies such as the minimum wage are universal (not income-tested) and aim to set labor standards in the low-wage sector regardless of income level.

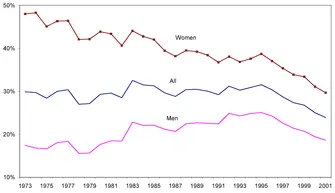

How much low-wage work is there in our economy? To operationalize the concept, we need a measure of low-wage work. A common and accessible measure used by numerous analysts is the “poverty level wage”. Figure 1.1 shows the share of low-wage workers with low-wage defined as the share of workers earnings less than the poverty line for a family of four divided by full-time, full-year work, or 2,080 hours, 1973–2000. Thus, this is the wage—$8.70 in 2001—that would lift a family of four with one year-round worker to the poverty line.

Note that this choice of wage level is largely arbitrary, though it has been used in other work of this type (note also that while the level is derived from the poverty threshold for a family of four, the data in the figure reflect no consideration either income or family size).2 The point is simply to choose an hourly wage representative of pay in the low-wage sector, hold it constant through time, and observe what share of the workforce earns at or below that level. This answers the question of the prevalence of low-wage jobs generated by the economy over time.

Figure 1.1. Share of workers earning poverty-level wages, by gender, 1973-2001.

Source: Authors' analysis.

Figure 1.1 reveals that while the share of low-wage work in the economy has trended down recently, it hovered about 30% for most of the period, ending 24% in 2001.3 This share represents about 27 million workers in that year. Prior to 1995, note the very different trends by gender, as low-wage work trended up for men and down for women. The differences are mostly to the fact that female workers over this period made relative (to men) gains in occupations, education, experience. Men were also more negatively affected by the long-term decline in manufacturing employment and union density over this period. (These issues are explored below.) Still, the persistent gender gap is evident throughout the 28-year period.

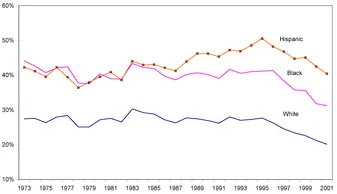

Figure 1.2 plots the same variable by race for white, black, and Hispanic workers. The racial gaps are evident in the figure; in 1989, whites’ rate of low-wage work was more than 10 percentage points below blacks and Hispanics. By the mid-1990s, about half of the Hispanic workforce earned low wages. The latter 1990s boom disproportionately lifted the real earnings of minorities and helped narrow the racial wage gap. This theme—the importance of tight labor markets in raising low wages—is one that we will emphasize throughout this chapter.

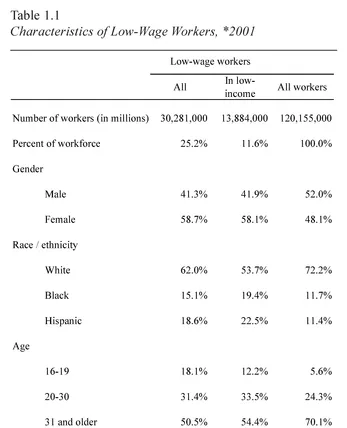

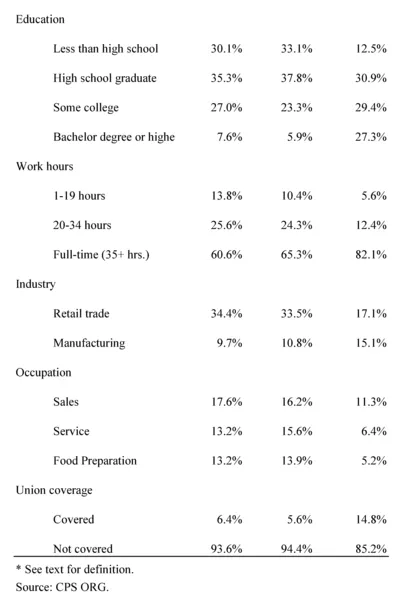

What are the characteristics of those who hold these jobs? Table 1.1 uses the same poverty-level wage definition as above, and examines shares for various characteristics. The first column is for all low-wage workers, while the second restricts the sample to those in families with less than $25,000. The third column provides data on all workers, so we can see where low-wage earners are over- and under-represented.

Figure 1.2. Share of workers earning poverty-level wages, 1973-2001.

Source: Authors' analysis.

Relative to the overall workforce, low-wage workers are disproportionately female, minority, younger, less highly educated, and less likely to work full time.4 Still, three fifths work full-time, and when we control for low income, the fulltime share increases to just below two thirds, compared to four fifths of the overall workforce. Note also that the 46% of workers who are both low-income and low-wage tend to be older and are more likely to be of minority status. Predictably low-wage workers are over-represented in low-end industries and occupations, and under-represented in manufacturing (though about 10% of low-wage jobs are in low-end manufacturing such as apparel and food products). For example, while 17% of the overall workforce are employed in retail trade, for low-wage workers, that share is doubled. Relative to the overall workforce, a small share of low-wage workers are either union members or covered by collective bargaining agreements.

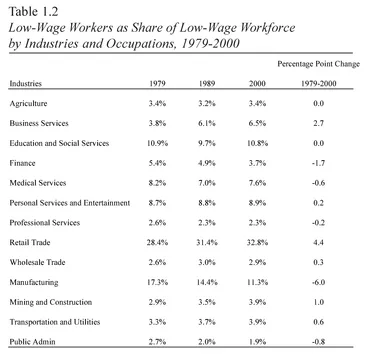

Sticking with our definition of low-wage work, Table 1.2 shows low-wage workers are distributed by occupation and industry, 1979–2000. The values in the table refer to the percent of low-wage workers in each year—each column sums to 100%. The final column shows how low-wage shares have changed over time.

Interestingly, with few exceptions shares have changed relatively little over time. A smaller share of low-wage workers are in manufacturing (there are also a smaller absolute number of such jobs), but this change is no larger than the overall decline in manufacturing employment as a share of total employment. Otherwise, the industry values show no large shifts. Similarly, a smaller share of low-wage workers are in clerical work; here again, however, the decline reflects the shrinking share of clerical jobs over time. Thus, low wages are less likely to be found manufacturing and slightly more likely to be in service occupations.

These values on the distribution of low-wage workers by industry occupation do not reveal any information about the impact of industry occupational shifts on the probability of low-wage work. In decompositions shown in Bernstein and Hartmann (1999), we show that while such shifts are important, they are generally about one fifth of the increase in the likelihood of low-wage work for men (recall that the likelihood for women fell over this period). important insight from this work is that while sectoral shifts mattered (industrial downgrading hurting males; occupational upgrading helping women), the larger factor driving the trend in low-wage work has been wage erosion within narrowly defined cells (by education, indu...