![]()

Chapter 1

The Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy: Modifications and Applications for a Variety of Psychological Disorders*

The introduction will provide a comprehensive review of the disorders that are discussed in subsequent chapters. In addition, the Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy will be described, and general guidelines for modifications are proposed.

Recently, there has been a movement away from the traditional approach to psychotherapy (a patient sitting on a couch as the therapist makes interpretations connecting the past to the present) to a more time-limited, goal-directed approach, with a particular emphasis on the present. This movement toward the more efficient delivery of psychotherapy serves several purposes. First, it helps patients recover in a shorter amount of time, which has implications for decreasing the negative impact of psychological distress in a variety of areas, including interpersonal relationships, employment, and personal finance. Second, it decreases the cost of psychotherapy while at the same time potentially increasing the number of patients who receive services. Finally, as researchers and clinicians continue to refine and improve psychotherapeutic techniques, it reinforces the scientific bases of psychotherapy and enhances credibility.

The movement has resulted in the establishment of a variety of treatments as efficacious (i.e., shown to work for a group of patients with a specific psychological disorder under well controlled conditions). For example, the current treatment of choice for a patient diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder is the combination of pharmacotherapy with exposure and response prevention. In some cases, there exists more than one empirically supported treatment for a specific psychological disorder (see Chambless & Ollendick, 2000, for a complete review of currently empirically supported therapies). Many different therapeutic techniques have been demonstrated to be equally efficacious for depression. For example, improvement in functioning is seen in depressed patients whether the primary treatment modality is pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, or a combination of the two.

Recently, Keller et al. (2000) demonstrated that the Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP), particularly in combination with pharmacotherapy, is efficacious in the treatment of chronic depression. CBASP is goal oriented, efficient, and simple to implement.

The Development of CBASP

McCullough (2000) developed CBASP specifically for the treatment of chronic depression. The approach combines behavioral, cognitive, and interpersonal techniques to teach the patient to focus on the consequences of behavior, and to use problem solving to resolve interpersonal difficulties. The study that launched CBASP as an efficacious treatment took place at 12 academic centers and included patients who met criteria for a chronic unipolar depressive disorder (i.e., Major Depressive Disorder, recurrent or Dysthymic Disorder). Patients were randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups: medication only (Nefazodone), psychotherapy only (CBASP), or combined treatment of Nefazodone and CBASP. Extreme care was taken to ensure the qualifications and training of the therapists administering psychotherapy. In addition, treatment fidelity was carefully monitored and controlled. Results indicated that patients in all three treatment groups improved substantially. However, those patients who received the combined treatment of Nefazodone and CBASP made even more significant improvements on posttreatment ratings, compared with those patients in either the medication-only treatment group or the psychotherapy-only treatment group. Thus, the authors concluded that their results contribute to the extant literature, suggesting that the combination of medication and psychotherapy in the treatment of depression is superior to either treatment alone.

Components of CBASP

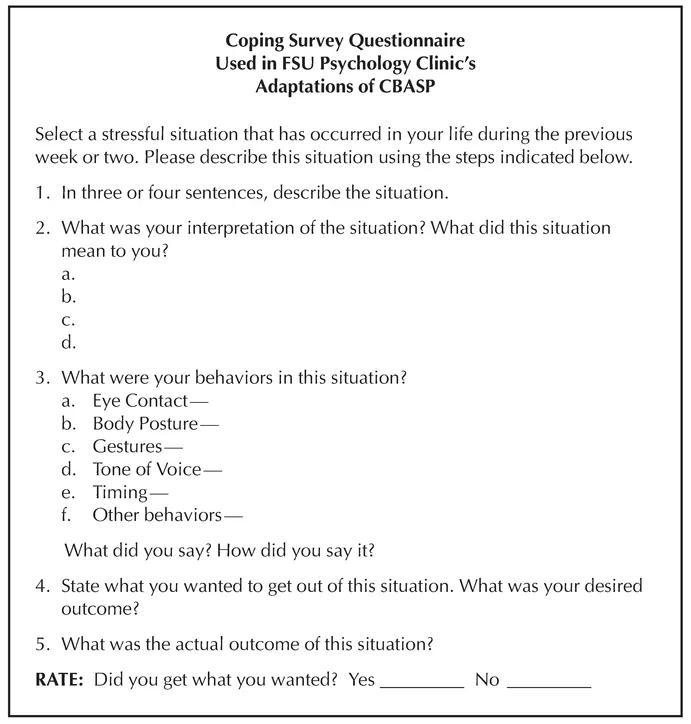

The primary exercise of CBASP is Situational Analysis, or SA, in which there is an elicitation phase and a remediation phase (McCullough, 2000). SA first requires the patient to verbalize his or her contribution in a distressful situation at three levels: interpersonally, behaviorally, and cognitively. SA is accomplished in five steps: describing the situation, stating the interpretations that were made during the situation, describing the behaviors that occurred, stating the desired outcome, and stating the actual outcome. When first beginning CBASP, the Coping Survey Questionnaire (CSQ)1 should be used both in session and as assigned homework (see Fig. 1.1). The CSQ is introduced in the first session as the tool with which CBASP is conducted. The overall goal of the treatment is to determine the discrepancy between what the patient wants to happen in a specific situation and what is actually happening. By examining the specific situations, the patient gradually uncovers problematic themes and ways in which he or she can get what is wanted.

The patient is told that he or she will complete CSQs about stressful or problematic interactions. The patient is also told that the situation will be discussed in session, along with what the patient thought, how he or she acted, and how the situation turned out compared with how the patient wanted the situation to turn out. Finally, the patient is told that this method will allow him or her to determine ways in which thoughts and behaviors are interfering with his or her ability to get the desired outcome.

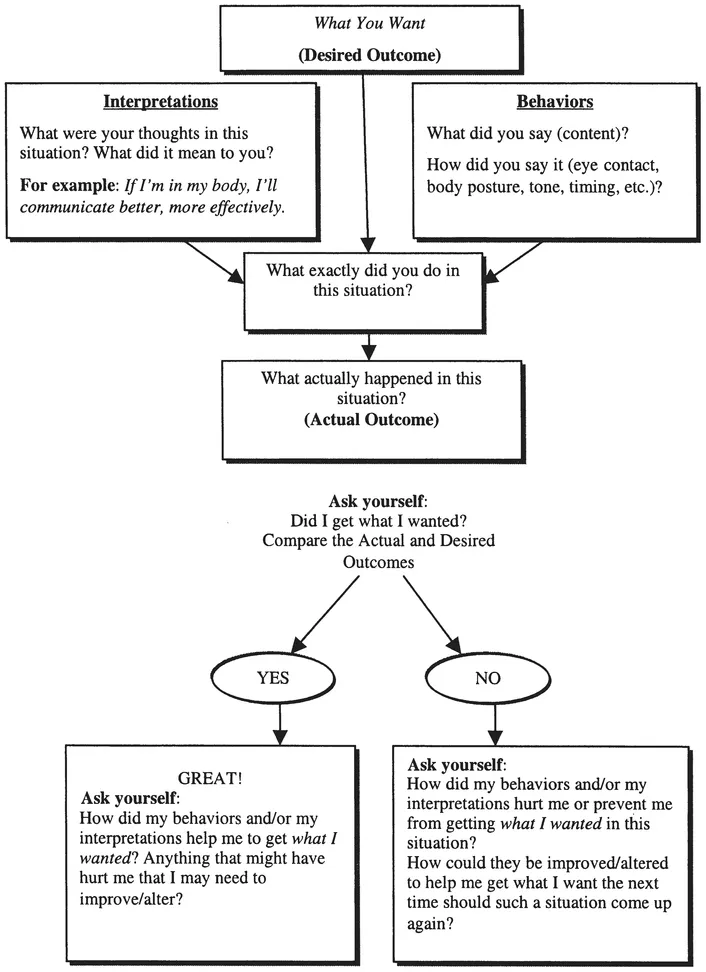

As noted, the CSQ is the primary tool of SA, and we have made modifications to McCullough’s original CSQ to facilitate the efficient use of this important tool, which is reflected in the descriptions of each of the steps. The CSQ is introduced in the first session. Providing the patient with several blank copies of the CSQ establishes the expectation that at least two CSQs are to be completed between sessions, which means at least one CSQ will be reviewed in session. Initially, completing one CSQ will probably take a full session; however, as the patient becomes more succinct when completing the individual steps and more efficient with using the CSQ, it is likely that several CSQs can be completed in one session. Eventual mastery of the steps of the CSQ is expected; however, patients should be required to complete a paper version of the CSQ as homework between every session to ensure consolidation of therapeutic gains. A graphical depiction of the CSQ can be found in Fig. 1.2, which can also be used as a patient handout to explain the process.

FIG. 1.1. Coping Survey Questionnaire used in Situational Analysis. Adapted from McCullough’s Coping Survey Questionnaire by Maureen Lyons Reardon.

FIG. 1.2. Graphical depiction of CSQ format used to facilitate discussion of the connections between thoughts, behaviors, and consequent outcomes. Adapted by Maureen Lyons Reardon.

In Step 1, the patient succinctly describes a problematic or stressful situation in an objective manner. The goal during this step is for the patient to provide a situation with a beginning, a middle, and an end, without editorializing or making interpretations about what happened. We refer to this as a specific slice of time, and our goal is for patients to describe very specific situations. The therapist may phrase the elicitation of Step 1 as “If I was a fly on the wall, what would I see?” The information presented in Step 1 needs to be both relevant and accurate. Because patients often provide irrelevant, extraneous information, instructing the patient to describe a discrete incident in three or four sentences is recommended.

During Step 2, the patient learns to identify the specific interpretations that were made during the situation. Depression-related interpretations tend to be global and negative in nature. The goal of the second step is for the patient to construct relevant and accurate interpretations, and the most effective interpretations are those that contribute directly to the attainment of the Desired Outcome (DO). This step tends to be the most difficult for patients to complete; thus, instructing them to describe two or three thoughts that popped into their mind often helps with identifying interpretations. Sometimes it is necessary for the therapist to prompt the patient by stating, “At the time, when you were in the situation, what did it mean to you?”

During Step 3 of SA, the patient identifies the specific behaviors that occurred during the situation. Particular attention is paid to the content of the conversation, the tone of voice, body language, eye contact, and anything else that the patient did (e.g., walking away). When identifying behaviors, the patient should attempt to use the tone of voice or facial expressions that occurred in the situation so that the behavioral details are accurately replicated. The goal of Step 3 is for the patient to focus on the aspects of his or her behavior that contribute to the attainment of the DO.

Identification of the DO is accomplished in Step 4.2 Articulating the DO is important because all steps are anchored or related to the attainment of the DO. The DO is the outcome that the patient actually wanted in the given situation. To facilitate the expression of the DO the therapist can ask, “What were you trying to get in this situation?” or “How did you want this situation to turn out?” It is important for the patient to identify a single DO per CSQ. Moreover, the patient’s goal in Step 4 is to construct DOs that are attainable and realistic, meaning that the outcome can be produced by the environment and the patient has the capacity to produce the outcome. Patients often have difficulty determining the appropriate DO because they begin by choosing an outcome that requires change in another person or a change in their emotions. The patient must always focus on how his or her own thoughts and behaviors influence situations, and, when focusing on how someone else reacts, the patient should be reminded that others can be influenced but not controlled.

Lastly, the identification of the Actual Outcome (AO) is accomplished in Step 5. The patient’s goal during Step 5 is to construct an AO using behavioral terminology that describes exactly what happened in the situation. Patients usually do not have any difficulty stating the AO; however, for patients who have difficulty articulating this step, asking the question “What did you really get?” might help. Once Steps 1 through 5 are complete, the patient compares the AO to the DO, answering the most important question — whether or not he or she got the DO. This completes the elicitation phase.

During the remediation phase, behaviors and cognitions are targeted for change and revised so that the patient’s new behaviors and cognitions in the situation contribute to the DO. Thus, during the remediation phase, each interpretation is assessed to determine whether it aided in or hindered the attainment of the DO. The remediation step focused on behaviors is similar to that done in the remediation step focused on interpretation: Each behavior is evaluated as to whether or not the behavior aided in or hindered the attainment of the DO.

If interpretations or behaviors are seen as obstacles to attainment of DOs, the solution is simply to alter them so the interpretations or behaviors are more likely to lead to DOs. Repetition of these steps in a variety of specific life situations is the core of the CBASP technique (McCullough, 2000).

Application of CBASP to Other Psychological Disorders

Although McCullough (2000) originally developed CBASP for patients with chronic depression, the general principles of CBASP can be applied to a variety of psychological disorders, and in some cases only minimal modifications to the original technique are necessary. As noted previously, the primary exercise of CBASP is SA, in which there is an elicitation phase and a remediation phase. This is accomplished using the CSQ. SA first requires patients to verbalize their contribution in a social encounter at three levels: interpersonally, behaviorally, and cognitively. During the remediation phase, behaviors and cognitions are targeted for change and revised so that the patients’ new behaviors and cognitions in the situation contribute to a desirable outcome. Because most psychological disorders result in some form of interpersonal difficulty, the use of SA across a variety of disorders makes intuitive sense. For example, patients with personality disorders undoubtedly have interpersonal conflicts, patients with social anxiety disorder may experience such extreme anxiety when conversing with others that the possibility of forming and fostering relationships is impaired, and patients with impulse control disorders, particularly anger management problems, may alienate others to the point that the relationship is left in ruins. Thus, SA via the CSQ can be used to address one of the common features in each of these disorders — interpersonal difficulties.

Personality Disorders

A personality disorder is defined as an enduring pattern of thinking, feeling, and behaving that markedly deviates from the expectations of one’s culture (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). This pattern of experience and behavior is pervasive, inflexible, and stable over time and leads to significant distress or impairment in the individual. There are three clusters of personality disorders. Cluster A consists of paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders; individuals diagnosed with a personality disorder in this category are often described as odd and eccentric. Cluster B consists of antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders; individuals diagnosed with a personality disorder in this category are described as dramatic or erratic. Finally, Cluster C consists of avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders; individuals diagnosed with these disorders often appear anxious or fearful. Relatively few treatments have been determined to be efficacious for personality disorders. In fact, according to Nathan and Gorman (1998), there are standard psychosocial treatments for Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and Avoidant Personality Disorder (APD) but none for other personality disorders.

The application of CBASP to personality disorders is described in Chapters 2 through 5, which cover Schizotypal Personality Disorder (STPD), BPD, Passive-Aggressive Personality Disorder (PAPD), and Personality Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PD NOS). STPD is characterized by a pattern of maladaptive interpersonal behavior and by specific cognitive and behavioral symptoms (e.g., stereotyped thinking, magical thinking, odd/eccentric demeanor, tangential speech). Previous studies indicate this disorder can be successfully treated with cognitive behavioral therapy. Chapter 2 describes modifications of CBASP that apply the use of this technique to STPD.

BPD consists of symptoms such as instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affect and a pattern of marked impulsivity. This disorder traditionally has been considered among the more difficult to treat, in part due to the interpersonal deficits these patients exhibit. Chapter 3 summarizes the application of CBASP to BPD and suggests ways in which it complements existing treatments for the disorder.

PAPD is described in Chapter 4. The disorder is characterized by a pattern of negativistic attitudes, passive resistance to the demands of others, and negative reactivity (e.g., hostile defiance, scorning of authority). This disorder is currently described in the appendix of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fourth Edition (DSM–IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), as a result of controversy surrounding the validity of the diagnosis. There is currently no empirically validated treatment for this disorder; however, CBASP seems to be a promising new frontier in reducing the attitudes and behaviors associated with PAPD.

PD NOS is the diagnostic label applied to patients who present with a combination of pathological personality symptoms that comprise the other personality disorders but do not present with symptoms that meet the full criteria for any one personality disorder. These symptoms ...