INTRODUCTION

Academics from multiple disciplines, as well as nonprofit practitioners, have examined the internal motivations of individuals to make charitable contributions and voluntarily provide public goods. These scholars include economists (e.g., Kolm & Ythier, 2006; Powell & Steinberg, 2006), psychologists (e.g., Batson, 1990; Carlson, Charlin, & Miller, 1988; Clary, Snyder, Ridge, Copeland, Stukas, Haugen, & Miene, 1998; Penner, Dovidio, Piliavin, & Schroeder, 2005; Piaget, 1932; Weber, Kopelman, & Messick, 2004), sociologists (e.g., Havens, O’Herlihy, & Schervish, 2006), and nonprofit marketing and management scholars (e.g., Bennett & Sargeant, 2005). In economics, models of altruism (e.g., Becker, 1974), impure and warm-glow altruism (e.g., Andreoni, 1989, 1990), conditional cooperation (e.g., Fischbacher, Gachter, & Fehr, 2001), and reciprocity (e.g., Sugden, 1984) have been developed and tested in the experimental laboratory (e.g., Croson, 2007).

We examine the setting of individual contributions to public radio. Individual donations are the bread and butter of the public broadcasting industry in the United States. Over 800 member radio stations collected $275 million from individual donors in 2006 (Corporation for Public Broadcasting Revenue Report, 2006). These donations were collected using the fundraising principle that public services drive public support (Audience Research Analysis, 1988, 1998, 2010). That is, people listen, so they give; when audiences decline, so do donations.

This fundraising wisdom inspires sophisticated practices like distinguishing between core listeners and fringe listeners, understanding how listener loyalty translates into donations, and how to design fundraising appeals to remind people of the importance of listening to public radio in their lives. This mental model of fundraising, however, assumes a one-to-one relationship between a station and a donor in the transaction of service and support. However, these practices do not typically incorporate the social environment surrounding listeners and donors into the equation.

In contrast, our research expands the vision of giving to include the social environment of donors to public radio. The focus of this research is to understand the social environment surrounding both listening and donating behavior. Our research highlights the observation that listeners and donors are not only individuals who act on their own; they are also social animals (Aronson, 2007). They live in connection with each other. Audience research (Audience Research Analysis. 1988, 1998, 2010) can tell us how much each individual listens, but it does not tell us how long they listen with friends, how much they talk with others about the programs they listen to, how often they discuss their donation decisions with their family, how their donations are influenced by others’ donations, or how much listening and donating constitute an important part of who they are (their self-identity). It is this social context surrounding listening and donating that our research sets out to study.

A relevant stream of literature (and one to which these authors have contributed) goes beyond internal motivations of donors and investigates the impact of social information—knowing whether and what others contribute—on one’s own contribution. The first part of our chapter (“Social Information”) reviews this literature and draws practical implications from it that will be of interest to fundraisers.

While this previous work demonstrates that social information about others’ giving can influence one’s own, in the second part of this chapter (“Social Networks”) we discuss the impact of a different type of social information on giving: information about others’ use or value for the organization. Models of charitable giving typically balance these two factors within the individual. In deciding whether or how much to give, the individual compares his value for the services the organization provides with the contribution he is considering. He contributes up to the amount that he values the work the organization is doing. In the “Social Networks” section we suggest an expanded conception of the individual’s value of the organization, which includes not only the value the individual receives, but also the value his social network receives. What they value and what is important to them increases their happiness, and thus our own. Thus supporting services that provide value to one’s social network in turn supports one’s own values.

SOCIAL INFORMATION

The body of research described in this section studied the effects of social information on giving. Previous research on social information and social norms suggests that people’s behavior is driven by their perceptions of others’ behavior (Crutchfield, 1955). Cialdini, Reno and Kallgren (1990) describe these perceptions as descriptive social norms, which specify what is typically done in a given setting (what most people do), and differentiate these from injunctive social norms, which specify what behaviors garner approval in society (what people ought to do).

Many studies have demonstrated the influence of descriptive and injunctive social norms on subsequent behavior in varying situations. For example, they have been shown to influence the choice of exercising during leisure time (Okun, Karoly, & Lutz, 2002; Okun, Ruehlman, Karoly, Lutz, Fairholme, & Schaub, 2003; Rhodes & Courneya, 2003); communication styles during wedding ceremonies (Strano, 2006); team-based innovations in the workplace (Caldwell & O’Reilly, 2003); littering (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990); and stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination (Mackie & Smith, 1998). The relationship between social norms and behavior has also been shown for specific subpopulations, including breakfast food choice among children (Berg, Jonsson, & Conner, 2000), alcohol misuse among college students (Walters & Neighbors, 2005), smoking cessation among smokers (Van de Putte, Yzer, & Brunsting, 2005), and condom use among drug users (Van Empelen, Kok, Jansen, & Hoebe, 2001). In this body of research we are the first to look at the influence of social norms, and descriptive social norms in particular, in the domain of donations to public radio. Our variable of interest is the level of giving by individual donors.

In Shang and Croson (2009), we amended the script that volunteers used when listeners called in to make their donation. After being greeted by the volunteer, callers were randomly assigned to a control condition (where they were given no social information) or were told “We had another donor who gave $X dollars. How much would you like to give today?” The amounts that callers were told another donor had given were varied ($75, the median gift level of this station; $180, the 80th percentile of gifts to the station; and $300, the 95th percentile of gifts to the station) to examine their impact on giving.

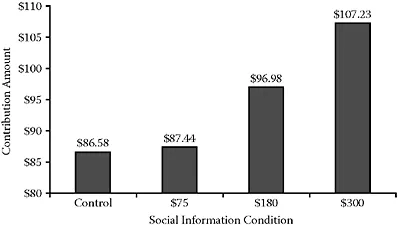

We found that providing social information increased the amounts that people donated, but that there was an optimal “specimen” amount that was most effective. This is illustrated in Figure 5.1 where the average gift from new donors in the control condition (i.e., where donors are given no social information) is shown alongside the cases where the caller is told about another donor having made a gift

of $75, $180, or $300. In this case, citing a prior donation of $300 was the most profitable, and increased giving by an average of 29%.

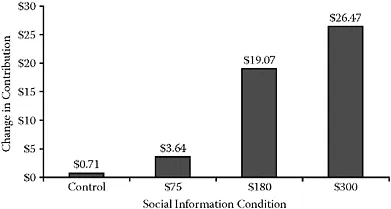

A similar picture was obtained with donors who were calling in to renew their existing membership. Figure 5.2 shows that donors not exposed to the social information gave almost the same amount as they had given last year (up only 71 cents). Those donors exposed to social information, however, gave markedly more than they had previously given, and in the $300 condition, their contributions increased by $26.47.

These results raise the natural question of the optimal level of social information to provide. After some further studies and calibration exercises (Shang & Croson, 2006), we conclude that the ideal amount to choose is between the 90th and 95th percentile of the value of previous gifts to the station. Croson and Shang (2009) find that higher levels of social information actually decrease individual giving.

These first three studies all examine the impact of upward social information (another donor is giving more than the target). But what is the impact of downward social information? Shang and Croson (2008) answered this question using a direct mail campaign for the same radio station.

In this study, solicitations were sent to existing donors asking them to renew their memberships. We collected the previous year’s contribution of each donor from the station. Some donors received materials that indicated that another donor had contributed exactly the amount that they had contributed in the previous year (although they were not reminded of what that contribution had been). Others received materials that indicated that another donor had contributed more than their previous year’s contribution. Still others received materials that indicated that another donor had contributed less than their previous year’s contribution.

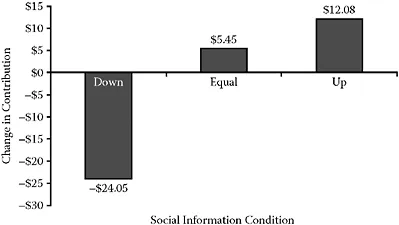

Figure 5.3 describes the change in contribution exhibited by donors in each of the three conditions. Donors who received social information higher than their previous year’s contribution increased their contribution by $12 on average. Donors who received social information that was the same as their previous year’s contribution increased their contribution by $5.45 on average. However, donors who

received social information lower than their previous year’s contribution decreased their contribution by $24 on average.

This research illustrates two important features of social information. First, social information is as robustly effective at influencing contributions when delivered via mail (or in writing) as when it is delivered over the phone (or in person). This provides an important robustness check to the results from the previous studies. Second, downward social information is about twice as impactful as upward social information; the reduction in contributions as a result of downward social information is twice as large as the increase in contributions as a result of upward social information. This suggests an important caveat to the use of social information in fundraising. Appeals need to be customized to the donor so they do not represent (too much) downward social information, which will likely decrease contributions.

Intuitively, one might imagine that causing someone to increase their giving this year might reduce it the next (intertemporal crowding out). This turns out not to be the case, and in fact, quite the opposite effect occurs. Cont...