![]()

1 Things that shape history

Material culture and historical narratives

Giorgio Riello

Beds, pans and teacups, mirrors and combs, stools and chairs, sheets, covers, Coca-Cola bottles, Walkmans, cars and old coaches, diamonds, chests of drawers, toilets, stiletto shoes, antiquities, oddities and monstrosities. This is not a summary of items appearing on The Antiques Roadshow but a succinct list of things that appear as subject matters dealt with in articles and books written by historians. This list should not mislead us into thinking that historians consider ‘things’ as either important or interesting per se. In the reading list of material culture, one will not find any of the brilliant old-fashioned antiquarian types of titles such as ‘Old English bedsteads’ or ‘Some early English sea service buttons’.1 Historians are as or even more interested in a thick conceptual ‘sauce’ that includes savoury concepts such as gender, class, identity, politics, and the usual carousel of presentations and representations, perspectives, semiotics and theoretical underpinnings.

This essay reflects on the relationship between the methodologies and conceptual categories used by historians and their recent engagement with material culture. My specific concern is the relationship between artefacts and the large concepts that historians constantly mobilize to understand the past – what I call ‘narratives’ or ‘tropes’. Historians are increasingly presented with isolated objects, often de-contextualized, which they seek to fit (alongside other events, facts and analyses) within the broad narratives that preside over history as a subject. The rise of capitalism, the Renaissance, the Industrial Revolution, globalization and the like are all ‘big boxes’ that even the most astute postmodernist cannot avoid without difficulty. Historians also construct their scholarship in very precise ways, by adopting widely shared methodologies. This chapter asks whether material culture helps historians to do things differently.

I will address these issues by considering three case studies, which I suggest represent three of the ways in which history relates to material culture. I have chosen a rather tatty eighteenth-century stomacher, a seventeenth-century broken wine cup and a nineteenth-century print. However, before looking at this selection of items it is worth reviewing the general approaches historians have employed in the burgeoning field of material culture studies.

Varieties of material cultures

Historians have survived, even thrived, during the last two centuries with little or no engagement with objects. In many ways, it appears that historians do not feel at ease when dealing with material things.2 Yet, arguably objects reveal history in important ways and, indeed, the study of material culture has significantly influenced the field of history in recent years.3

History from things

A first way in which historians relate to material culture is by concentrating on its material form and treating it in the same way in which they treat a manuscript, a diary, an inventory or an image: objects as primary sources. In this case, artefacts are important because they can be used as evidence of something that was part of the past. This is what I call history from things, in which material artefacts are used as raw materials for the discipline of history and the interpretation of the past. The pay-off for historians is a wider (more numerous but also more varied) collection of sources through which to back their arguments and interpretations.

History of things

Historians are not necessarily interested in uncovering another saucepan, or finding out a previously unknown variety of medieval roasting fork. In the subject of history the material finding does not constitute research and will not be given much space in the pages of a historical publication. The development of studies on consumption and the coming of age of design as respectable fields of historical enquiry have meant an increasing interest in material artefacts. Today the bulk of the history of material culture is about history of things, that is to say the historical analysis of the relationship between objects, people and their representations.4

Things are important in all those areas of history in which they played a relevant part. If a historian is interested in analysing the philosophical thought of Voltaire, he or she will find little help by examining Voltaire’s teacup, or any eighteenth-century teacup for that matter. But if one is instead interested in considering the culture of politeness, the examination of tea services, snuff boxes and Hogarth prints might be very relevant. There are many different approaches towards the history of things: the finding of deeper personal meanings in individual objects (as magisterially done by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich), or less personal, quantitative analysis of ownership patterns (as found in the scholarship of Lorna Weatherill).5 In both the object is not a ‘prop of research’ but the very subject matter of analysis. In this case the pay-off for historians is the capacity to extend their coverage by producing new fields (and new depths) of historical enquiry, often based on a high degree of interdisciplinarity.

Table 1.1 Varieties of material culture, methods and narratives

| Variety of material culture | Cases | Things, methodologies and narratives |

| History from things | 1 | Thing | Methodology | Narrative |

| | A 'concealed' stomacher | Integration of sources | Choice of a narrative |

| History of things | 2 | Methodology | Narrative | Thing |

| | Interdisciplinary research | The consumer revolution | Pottery excavated in Jamestown |

| History and things | 3 | Narrative | Thing | Methodology |

| | | The Industrial Revolution | A cut image of a flying machine | Revising positivism |

History and things

A third way of considering material artefacts is by positioning them outside history altogether. The subject of history has been slow at accepting this more ‘democratic’ vision of material culture in which material objects are not in a servile position to historical scholarship. Other disciplines, such as sociology, archaeology and anthropology, have developed flexible methodologies of analysis of material artefacts by stating their heuristic independence. History has been slow to recognize the material world’s capacity to challenge the overall concept of the analysis of the past by evoking and shaping new processes of gathering, systematizing and presenting ideas. Artefacts have long brought the past to life for wider audiences via museum displays and television documentaries and dramas. They provide both immediacy and a direct way for people to relate to the past, qualities of which professional history has been wary. History and things provides a qualitative pay-off for historians: the capacity to unlock more creative and freer ways of conveying ideas about the past that are not necessarily mediated by written language in books and articles produced by professional historians.

The rest of this chapter will ‘put into practice’ these different approaches. I wish to show how there are different ways in which material culture relates both to the ‘big’ concepts of history and to the methodologies through which historians construct their scholarship. The following case studies present objects from 1600 to 1850, and are intended not as a guide for ‘ideal’ historical analysis,6 but as a reflection on how artefacts have inspired historians to ask new questions, to challenge established paradigms and formulate new interpretations (Table 1.1).

Concealed capitalism: things that money can't buy

Things: a 'concealed' stomacher

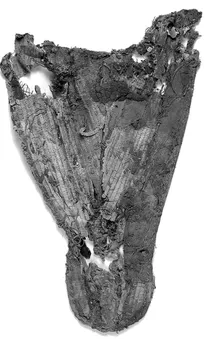

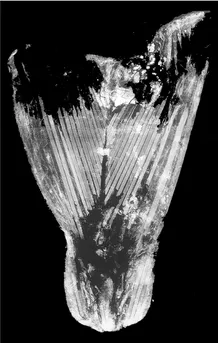

In 1980 Mr and Mrs Maynard moved into their new cottage in Nether Wallop, Hampshire, UK. The house was in a state of disrepair, and restructuring soonstarted. During the process, the Maynards uncovered what appeared at first sight to be a bundle of rubbish stuck in the chimney breast. On closer examination, they discovered that the bundle consisted of a velvet waistcoat and a stomacher, wrapped in paper. Once the excitement of this finding waned, the Maynards put all objects in a plastic bag in the old bread oven ‘as we didn’t quite know what to do with them’.7 One of the paper fragments is a newspaper dated 1752, thus providing the earliest date when they were left there, though the remaining objects are earlier. The stomacher (Figure 1.1) pre-dates the concealment and was originally a corset. Signs of wear and repair suggest that at some time, probably in the early eighteenth century, it was cut down into a stomacher. The garment is also atypical because the material is stiffened with strips of whalebone.8

Figure 1.1 Early eighteenth-century stomacher found at a cottage in Nether Wallop, Hampshire, United Kingdom, and an X-radiograph showing strips of whalebone. Deliberately Concealed Garments Project, Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton CG8.a. © The Textile Conservation Centre, University of Southampton and Sonia O’Connor, University of Bradford.

The Maynards’ finding is not unique. What they found was a cache of ‘deliberately concealed objects’. The practice of concealing objects, especially garments, in the very fabric of buildings was undertaken from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century in many parts of the world, and especially in Northern Europe, North America and Australia.9 The demolition and restructuring of old buildings has unearthed many such objects. In the late 1960s the Northampton Boot and Shoe Collection started preserving and cataloguing footwear concealed in buildings.10 Since 1998 the Concealed Garments Project at the Winchester School of Art has been, under the direction of Dinah Eastop, recording, preserving and interpreting concealed garments and other objects found in British buildings.11

Why did people decide to hide a shoe or a stomacher in the wall of their house? This question has no definitive answer. Archaeological analyses suggest that they were primarily concealed in junctures between old and new parts of buildings or within points of entry and exit such as doorways, windows and chimneys (Figure 1.2).12 The fact that th...