WK: Willkommen im Cafe Lwidtmann, Herr Kahr.

BK: Thank you, Herr Kerl. I am very honoured to be here, and I am so grateful that you have agreed that I might interview Professor Freud in your historical establishment.

WK: Professor Freud has long been one of our most distinguished guests. We are very proud that he has chosen the Café Landtmann as his Kaffeehaus.

BK: Vienna boasts so many wonderful Kaffeehäuser.

WK: Ja, ja, we have many coffee houses, this is true. But if you are to interview Professor Freud, you must speak in the Viennese way. I can see that you did not learn your German in Vienna: am I right?

BK: You are correct.

WK: I know this because you placed the accent on the first syllable of the word Kaffeehäuser. That is what the Germans do. They will say Kaffee, meaning coffee in your language. We Viennese, by contrast, pronounce it like the French, and we say Kaffee. We place the accent on the last syllable, not the first. Professor Freud always asked for Kaffee. I think you need to know that.

BK: I am very grateful to you Herr Kerl. Thank you.

WK: It is of no consequence. Professor Freud speaks excellent English.

BK: Indeed.

WK: We were discussing Vienna's Kaffeehäuser.

BK: Ah, yes . . .

WK: You must understand that in its heyday, before the war . . .

BK: The Second World War?

WK: Der Zweite Weltkrieg, ja. Before the Second World War, our coffee houses occupied a very special place in Viennese life. Everyone came here. And when they came, they stayed. Not like your Starbucks of today, with people popping in and out. In our day, the Viennese would come for hours at a time, and they would drink coffee, read the newspapers, eat pastries, meet friends . . .

BK: Much more like a social club.

WK: A place for coffee . . . for food . . . for conversation. You could call it a social club. But also an intellectual club.

BK: Writers and artists have always had a particular penchant for the Kaffeehäuser, I believe.

WK: The writers would often spend ages here, producing reams and reams of poems, and pages of novels. Many an artist became a Stammgast.

BK: Stammgast? A regular guest?

WK: Yes, a "regular", as you would say in English.

BK: Ah, yes. And Professor Freud became a Stammgast here at the Café Landtmann.

WK: Our most prized Stammgast. We have always been very honoured that he patronised us in this way. You know, the Professor could have frequented the Café Demel on the Kohlmarkt – very fine pastries at Demel, so I'm told – or the Café Hawelka, on the Dorotheergasse, or the Café Sperl on Gumpendorferstraβe. But he came here, to the Café Landtmann.

BK: You must be very proud.

WK: Very proud.

BK: I remember having read a lovely memoir by an Austrian writer called Joseph Wechsberg . . .

WK: This name I do not know.

BK: A very fine writer who emigrated to the United States in 1939, I believe. Herr Wechsberg made a very amusing observation about the Kaffeehäuser of Vienna, He quipped, "It was said that some men had more than one woman but only one coffeehouse."

WK: That is absolutely true. People came here for the Jause.

BK: The Jause?

WK: That is a Viennese invention, to be sure: a mid-afternoon break in which patrons could drink coffee with whipped cream, eat pastry, and indulge in much gossip!

BK: Tell me about the history of this Kaffeehaus, Herr Kerl.

WK: We opened here on the Ringstraβe in 1873. Franz Landtmann, from whom we take our name – a most distinguished cafetier – founded this establishment, and then, in 1881, Herr Landtmann sold the café to me and to my brother Rudolf.

BK: But you kept the Landtmann name.

WK: We kept the Landtmann name, ja. And still we have it.

BK: And you are very near to the university, the Universität zu Wien. That must have been rather convenient for Professor Freud, who lectured there.

WK: We had many men from the university come here for coffee, for cake, for reading the newspapers. Many very well-educated university men.

BK: It really meant something, to teach at the university . . . before the Weltkrieg.

WK: We have always treated our scholars with deep respect. Just as they treated the Cafe Landtmann with deep respect.

BK: You mentioned the Second World War earlier – den Zweiten Weltkrieg – but you had already died by that point. You worked here, I believe, during dem Ersten Weltkrieg, the First World War.

WK: Certainly we had our difficulties. Vienna suffered terribly from restrictions and shortages during the war. Very bad food shortages.

BK: With very painfully cold winters, so I understand.

WK: Indeed. Do you know that in August of 1915, I had to remove Einspänner coffee from our menu because of the difficulty we had obtaining milk. Also the Sacher Torte . . . which we always served with whipped cream. And then in November of that very same year, we had to replace sugar wife saccharine. Most distressing. But we survived somehow. It would be many years before Austria enjoyed Schlagobers again.

BK: Coffee with whipped cream.

WK: Ja, coffee with whipped cream.

BK: The Kaffeehaus holds quite a special place in the heart of the Viennese.

WK: Very special. Very special indeed. And I am so pleased that you have pronounced Kaffeehaus now in our Viennese way.

BK: Thank you. I shall do my very best.

WK: You have Viennese ancestry, I believe.

BK: It pleases me to tell you that I do.

WK: I know this from your family name Kahr, which is not, I think, Anglo-Saxon.

BK: Many of my family members did come from Austria generations back, so I have a great interest in your country and, especially, in your capital city.

WK: But you have never lived in Vienna yourself.

BK: I regret to tell you that I have not.

WK: I feel sorry for you. Vienna is a very special place, and not only for the Kaffeehäuser, you understand.

BK: I do indeed.

WK: But forgive me, I see my Oberkellner has not brought you anything to eat or to drink.

BK: Oberkellner?

WK: You would say, I think, "head waiter" . . . the Herr Ober.

BK: Ah, of course. Actually, I think I shall wait until Professor Freud arrives.

WK: But you have made such a long journey here from London. Can I not bring you some Krapfen or some Gugelhupf?

BK: How very tempting, but I do think I will wait.

WK: Of course.

BK: You have a large team working for you, I can see.

WK: Yes, as the cafetier, I have the task of supervising the many waiters who work beneath me and also the little Pikkolo boys beneath them.

BK: Pikkolo boys?

WK: These are the youngsters who fill the glasses of water.

BK: I think that this would not be permitted today, in the twenty-first century.

WK: Perhaps not.

BK: Thank you for explaining the life of the Kaffeehaus to me. I feel much better prepared already.

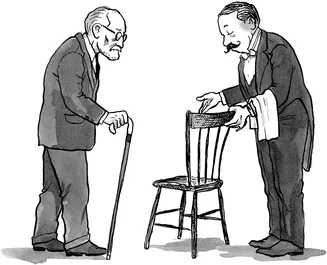

WK: Of course. But I see that Professor Freud has just arrived.

BK: Oh, gosh. So he has.

WK: You are nervous?

BK: I am very nervous.

WK: But he is a very polite, very kind man. You have no need to be nervous.

BK: You must understand, Herr Kerl, that I have been studying Professor Freud's work for almost the whole of my life.

WK: He will be very pleased to hear that. But look, here he comes. Please do compose yourself. I will introduce you.

WK: But you must be very tired after your journey from . . . well, you know where, Herr Professor, Please do sit.

SF: I am tired, but I am also very disbelieving that I am back in Vienna. I have not been here since ... let me see, when did I leave?

BK: You left on 4th June, 1938.

SF: Herr Kerl, this man has indeed been studying my life.

BK: He has come all the way from England to see you.

SF: Well that is not very sensible. I died in England. Could we not have met there?

BK: I had thought, Professor Freud, that it might be pleasant to speak to you here in Vienna, where you invented psychoanalysis.

SF: Of course, of course. But still, it is such a long journey back for me. You understand?

BK: Well, yes, of course. As I have already said, I am really most grateful.

WK: Gentlemen, I trust that you will have a most pleasant interview. My waiters and I will be on hand to attend to your every desire. May I have the honour of bringing your first coffee to you personally, Professor Freud?

SF: Not just yet, Kerl. I am still adjusting to the idea that I seem to be alive again after all this ...