- 350 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book studies the origins and development of population geography as a discipline. It explores the key concepts, tools and statistical and demographic techniques that are widely employed in the analysis of population. The chapters in this book:

- Provide a comprehensive geographical account of population attributes in the world, with a particular focus on India;

- Study the three major components of population change – fertility, mortality and migration – that have remained somewhat neglected in the study of human geography so far;

- Examine the salient social, demographic and economic characteristics of population, along with topics such as size, distribution and growth of population;

- Discuss major population theories, policies and population–development–environment interrelations, thus marking a significant departure from the traditional pattern-oriented approach.

Well supplemented with figures, maps and tables, this key text will be an indispensable read for students, researchers and teachers of human geography, demography, anthropology, sociology, economics and population studies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

Human elements in geography

Geography has traditionally been concerned with a man-environment relationship, and, therefore, man and his activities on the earth’s surface have occupied an important place in the discipline for a very long time. Nevertheless, with a greater emphasis on physical aspects, human elements were by and large missing from the concern of geographers for quite some time. Towards the end of the 19th century, however, the foundation for what came to be known as ‘human geography’ was already laid. It was Friedrich Ratzel (1844–1904) who established the new sub-discipline i.e. human geography for which he coined the term ‘anthropogeographie’ (Kosinski, 1984:15).

In 1882, Ratzel, considered as the single greatest contributor to the development of the geography of man, published the first volume of his book, entitled Anthropogeographie, in which he traced the effects of different physical features on the course of history (James and Martin, 1981:169). The second volume of Anthropogeographie was published in 1891. His works were quite influential in attracting the attention of scholars to population and its various attributes. Ratzel had keen interest in the mode of life of different tribes, races and nations. During his visits to the United States and Mexico during 1874–75, he developed interest in the life of people of not only German origin but also other minority groups such as the Indians, the Africans and the Chinese. In fact, it was his visits to the New World that led him to formulate general concepts regarding geographical patterns resulting from the contacts between aggressively expanding communities and the retreating groups. It was such research experience that had aroused his interest in the study of human geography (Dikshit, 1997:68).

Ratzel had a large number of followers in Europe and North America, and his Anthropogeographie flourished in Germany and outside, especially in France and the United States. But the views of Ratzel and his followers on man-environment relations were essentially deterministic in nature, wherein the population phenomena were explained in terms of the influence of physical factors mainly. However, some German geographers, notably Kirchhoff, using the opposite approach to the study of human geography focussed on man himself instead of describing the influence of the physical earth on human affairs (James and Martin, 1981:169). Ratzel’s second volume of Anthropogeographie was written from this perspective (Dikshit, 1997:69; Hartshorne, 1961:91; James and Martin, 1981:169), but it is interesting to note that Ratzel came to be known as a deterministic more from his first volume than the second one.

Alfred Hettener, another German geographer and a contemporary of Ratzel, regarded the study of population as an integral part of the general field of human geography. In his analysis of the separate branches of human geography, he singled out population and gave it equal prominence with other popular topics of that time (Trewartha, 1953:75). Along with density and numbers, Hettener treated the dynamics of population, i.e. regional birth and death rates, in-migration and out-migration, with equal importance in studies on population in geography. He emphasised that geographers should not confine their studies to biological phenomena only but also look into the social qualities, as they are equally important depending upon prevailing economic, political and socio-psychological conditions. Hettener’s observations on the significance of the study of population in geography are, thus, among the most direct and illuminating on the issue (Trewartha, 1953:75).

In France around the same time, a viewpoint, contrary to determinism and popularly known as possibilism, was emerging as a guiding point for studies in human geography. Paul Vidal de la Blache (1845–1918) is credited for the development of this ‘new geography’ in France. The concept of possibilism envisaged that nature sets limits and offers possibilities for human activities, but the way man reacts to these possibilities depends on gene re de vie or the way of living, or what we may call as culture. Vidal’s monumental work Principes de geographie humane (or subsequently translated into English as Principles of Human Geography) was published posthumously in 1921. Vidal de la Blache devoted one whole part or, one third, of his book on the study of population (James and Martin, 1981:191–2; Trewartha, 1953:74).

The ideas of Vidal de la Blache on human geography were later elaborated and popularised by his disciple Jean Brunhes. While analysing the elements of human geography in his volume Human Geography, Brunhes gave a very high position to the unequal covering of population on the earth’s surface. Brunhes was of the opinion that two world maps were of chief importance in the understanding of human geography – a map of water and a map of population. To him, any description of population can, however, only be made through the spatial distribution of the dwelling and the morphology of settlements.

The works of Vidal de la Blache and his followers were undoubtedly instrumental in generating interest among fellow geographers to study human beings and their activities. However, as Trewartha (1953) later pointed out, their emphasis was so much on the cultural landscape i.e. the product of human activities on the earth, that population itself was by and large neglected. Though Vidal de la Blache did incorporate population distribution in the scheme of Human Geography, he completely ignored other geographical aspects and made no attempt to arrange and classify its content (Trewartha, 1953:74). Jean Brunhes, too, completely ignored the qualities or characteristics of population in his treatment.

Though several studies dealing specifically with population did appear in Europe, the United States and Russia in the late 19th and early 20th century, on the whole population remained a neglected field in the overall scheme of human geography throughout much of the first half of the last century. In other words, population geography was largely subsumed within the descriptive Human Geography mainstream (Barcus and Halfacree, 2018:6). After the Second World War Kabo made an attempt to gain acceptance of the social geography of population as a separate discipline in 1947. In the year 1951, Pierre George, a French geographer, for the first time presented a very comprehensive treatment of the facts of population in geography. However, the emergence and recognition of population geography as a new sub-branch of human geography is largely attributed to the influential statement of Trewartha in the early 1950s.

Trewartha’s case for ‘population geography’

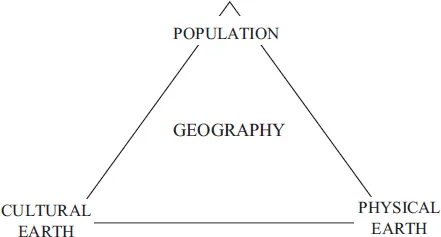

In his presidential address before the Association of American Geographers on the occasion of its 49th annual meeting held in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1953, Trewartha made a very forceful case for population geography. He was very critical of the neglect of the study of population in geographical studies. According to him, since geography is fundamentally anthropocentric in nature, the number, densities and qualities of population provide the essential background to all geography. In his view, thus, population is the pivotal element in geography, and around population all other elements are oriented. He said, ‘population is the point of reference from which all other elements are observed, and from which they all, singly or collectively, derive significance and meaning. It is population which furnishes focus’ (Trewartha, 1953:83). Trewartha proposed a three-fold sub-division of geographical science in place of the traditional two-fold classification – physical and cultural elements (Figure 1.1) – giving equal importance to man in relation to the physical earth and the cultural earth. He also said that ‘the study of population is logically the single most important approach to geography and the one in which regional concept has the broadest application’ (Trewartha, 1953:86). Therefore, any neglect to the study of population, according to him, will cause serious injury to the geographical science in general. Trewartha argued for a focus on man instead of concentrating on the cultural landscape alone. Trewartha presented a very comprehensive framework for geographical studies on population. The acceptance of the sub-field in human geography owes much to his influential appeal to his fellow geographers.

Figure 1.1Trewartha’s triad of geographical elements

Source: Based on Trewartha, 1953:81.

The roots of population geography

The early works of George (1951) and the influential statement of Trewartha before the annual meeting of the Association of American Geographers in 1953 are often considered as the turning point in the emergence of population geography as a separate field within geographical studies. The development, however, was not sudden. Nor was it unexpected. The roots of the sub-field can be located in developments that were taking place both within geography and outside during some earlier periods. While some can be traced, as early as in 19th century, others became potent forces in the first half of the 20th century. In addition to the growing recognition of the significance of human elements in geography, some other developments that were taking place in different parts of the world, and in different fields, helped a great deal in the emergence, and thereafter, growth and expansion of the sub-field.

As Kosinski (1984) and Clarke (1984) have suggested, growing availability of population statistics has played a crucial role in the emergence of population geography. Prior to the emergence of governmental and international agencies as sources of data, several private agencies, mainly in Europe, were involved in collection and compilation of population data. The UN agencies began publishing demographic statistics on a regular basis soon after the end of the Second World War. The UN also played a significant role in making the census data uniform and comparable across different countries by issuing guidelines and principles for census taking. The political and societal conditions both during and after the wars necessitated a geographical study of the ethnic composition of population of different regions. The need for a more detailed account of other demographic characteristics resulted in a switch over from macro- to micro-level studies, which in turn, facilitated population mapping. Population mapping has a long tradition in geography. In the earlier periods such maps were largely confined to distribution and density aspects. The growing availability of population data after the Second World War facilitated mapping of the other demographic attributes in different regions of the world.

Further, increasing use of quantification aided by access to computers helped geographers handle large data-sets. The onset of demographic transition in Europe sometime in the middle of the 18th century had resulted in population growth at a rate unknown previously in human history. By the turn of the 20th century, most of the developed countries had completed this transition. Around this time, death rates started declining in the less developed parts of the world. Remarkably, this decline, unaccompanied by a corresponding decline in birth rates, was much faster than what had earlier happened in the West. Thus, world population continued to grow at an increasing pace. Since most of the world humanity lives in the less developed parts of the world, a significantly larger proportion of the net addition in world population during the first half of the 20th century came from this part. There was a growing consciousness among the people regarding population expansion and its effects on economic development. The less developed countries had also begun experiencing redistribution of population within their boundaries from rural to urban areas. The emergence of large cities and their manifold problems became a compelling focus for research by geographers.

Admittedly, the consequences of these developments were not confined to geography alone. Other branches of study dealing with human population viz. demography and population studies were also undergoing parallel change. In fact, development in these related disciplines also played a crucial role in the emergence of population geography as a separate and independent sub-field in geography.

Population geography: definition, nature and subject matter

As noted earlier, population geography as an independent sub-field of human geography is a comparatively recent phenomenon. In the expression ‘population geography’, the term population signifies the subject matter and ‘geography’ refers to the perspective of investigation. Thus, ‘population geography’ can be interpreted as the study of population in spatial perspective. Etymologically, ‘population geography’ implies the investigation into human covering of the earth and its various facets with reference to physical and cultural environment. Population geography is concerned with ‘the geographic organisation of population and how and why this matters to society. This often involves describing where populations are found, how the size and composition of these population is regulated by the demographic processes of fertility, mortality and migration, and what these patterns of population mean for economic development, ecological change and social issues’ (Bailey, 2005:1).

In the academic world, any discipline is almost invariably defined by its subject matter (Johnston, 1983:1). The subject matter of population geography has been a matter of debate ever since Trewartha formally raised the issue in 1953. So is the case with the definition of the sub-discipline. According to Trewartha, population geography is concerned with the understanding of the regional differences in the earth’s covering of people (Trewartha, 1969:87). ‘Just as area differentiation is the theme of geography in general, so it is of population geography, in particular’ (Trewartha, 1953:87). Population geography is the area analysis of population which implies ‘a wider range of population attributes than most geographers have ordinarily included’ in their analysis (Trewartha, 1953:88). Trewartha proposed a very comprehensive outline of the content of the sub-discipline, which many subsequent geographers seem to have adhered to. Broadly speaking, the concern of population geography, according to Trewartha, can be grouped into three categories:

- 1 a historical (pre-historic and post-historic) account of population,

- 2 dynamics of number, size, distribution and growth patterns, and

- 3 qualities of population and their regional distribution.

Regarding the historical account of population, Trewartha suggested that where direct statistical evidence is not available, geographers should adopt indirect methods, and collaborate with anthropologists, demographers and economic historians. In Trewartha’s opinion, an analysis of world population patterns, population dynamics in terms of mortality and fertility, area aspect of over- and under-population, distribution of population by world regions and settlement types and migration of population (both international and inter-regional) form an important part of analysis in population geography. And finally, with regard to qualities of population he suggested two broad groups – physical qualities (e.g. race, sex, age and health etc.), and socio-economic qualities (e.g. religion, education, occupation, marital status, stages of economic development and customs, habits etc.). In his book entitled A Geography of Population: World Patterns, published in 1969, Trewartha arranged these topics in two parts. While the first included a geographical account of population in the past, the second incorporated all the characteristics of population including biological, social, cultural and economic characteristics.

John I. Clarke, who is credited with bringing out the first textbook on the sub-discipline in 1965 (at least after Trewartha had made the case of population geography in 1953), suggested that population geography is mainly concerned with demonstrating how spatial variation in population and its various attributes like composition, migration and growth are related to the spatial variation in the nature of places (Clarke, 1972:2). He opines that the main endeavour of population geography is to unravel the complex relationship between the population phenomena, on the one hand, and cultural environment, on the other. The explanation and analysis of these interrelationships is the real substance of population geography (Clarke, 1972:2). His book on Population Geography (1972) is spread over 11 chapters, and his treatment of the subject matter is in conformity with that of Trewartha, though not as comprehensive as that of the latter.

Zelinsky (1966) defines the sub-discipline as ‘a science that deals with the ways in which geographic character of places is formed by and, in turn, reacts upon a set of population phenomena that vary within it through both space and time as they follow their own behavioural laws, interacting one with another, and with numerous non-demographic phenomena’ (quoted in Hassan, 2005:8). On the delineation of the field of population geography, Zelinsky suggested that the list of human characteristics of practical interest in the population geography may be equated with ‘those appearing in the census schedules and vital registration system of the more statistically advanced nations’ (Clarke, 1972:3).

Daniel Noin in 1979, in his boo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of maps

- List of tables

- Preface and acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Sources of population data

- 3 Population distribution

- 4 Urban–rural distribution

- 5 Population growth

- 6 Age–sex composition

- 7 Literacy and education

- 8 Marital status

- 9 Economic composition

- 10 Fertility

- 11 Mortality and life table

- 12 Migration

- 13 Population theories

- 14 Population–development–environment interrelations

- 15 Population policy

- Glossary

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Population Geography by Mohammad Izhar Hassan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Demography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.