![]()

1

The Basics

Chapter Overview

This chapter provides a description of the basic accounting framework. After studying this chapter, you will:

- Be aware of the different purposes accounting serves;

- Understand what an account is;

- Understand the difference between accrual and cash accounting;

- Know the two equations which underlie the income statement and balance sheet, respectively;

- Gain insight into a basic income statement, balance sheet, source and use of funds statement and a firm’s operating cycle.

* * * * *

Accounting serves several purposes, all at the same time. The following are some examples:

- It’s used to keep score. It answers questions like “How are we doing?” Are we making a profit? If so, how much? Are we losing money? How is the West Coast division doing compared to the East Coast division?

- It directs attention to problems and opportunities. Is our inventory getting too large? Is our product getting out on time? Are we collecting our accounts in a timely fashion? What is happening to our profit margin?

- It provides information needed to control costs. Before managers can control costs they need to know how much the costs are, how much the costs should be and what it is that causes them. A properly designed accounting system will provide this information.

- It provides information needed for planning. Before managers can make plans they need to know how costs and profits react to changes in volume and production methods. For example, some costs will change proportionately with changes in production, some will change more than proportionately and some will not change at all.

- And it provides information for decision making. Should we make this component ourselves or should we outsource it? Should we buy or lease a piece of equipment? Do we want to accept this special order at a price below our normal sales price? Again, a well-designed accounting system can provide a treasure trove of information that will help managers answer these kinds of questions.

* * * * *

To understand how to use accounting data, first understand that the basic accounting framework is an amazing system of recording, verifying, summarizing and reporting business transactions. It is truly a thing of beauty.

The most fundamental component of that framework is an account. An account is simply a device, a pigeonhole if you will, to logically order whatever it is we want to keep track of. Want to keep track of cash? Create a cash account. Want to keep track of inventory? How much people owe us? How much we owe others? How much are our sales? Our expenses? Create an account for each. Accounts can be created and destroyed at will. Maybe we sold a building. If so, close the building account and get rid of it.

Back in ancient times BC (before computer), creating or closing an account was as simple as putting a sheet of paper in or taking it out of a loose-leaf notebook. Today it can be as simple as creating or deleting a column in an Excel spreadsheet.

Modern accounting rests on a marvelous invention called double-entry bookkeeping. Double-entry bookkeeping is a method of recording every transaction an organization makes. Every transaction that a company makes will have an impact on two or more accounts. At least one account will be debited and at least one will be credited. And remember that debits will always equal credits.

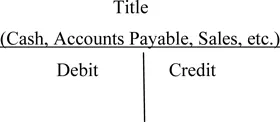

Structurally, accounts are very simple. They have three parts: a title (what we’re keeping track of), a left-hand side and a right-hand side. That’s it. Period. We call the left-hand side the debit side and the right-hand side the credit side. When we debit an account, we simply make an entry on the left-hand side of the account. A credit is made on the right-hand side. Debit does not mean increase or decrease. It means left and that’s all. Some accounts are increased when debited and some are decreased. The same holds true for credits. It all depends on the type of account. Sailors say “port and starboard.” Accountants say “debit and credit.” Below is an example of a “T” account.

There are five basic categories of accounts, with some variations thrown in to make it interesting. The five categories are: revenue, expense, asset, liability and owners’ equity and, of course, there are many examples of each.

Revenues are inflows of cash, increases in other assets or the settlement of liabilities resulting from the sale of goods and services that constitute an organization’s principal operations.

Expenses are the outflows of cash, the decreases in other assets or the incurrence of liabilities resulting from the performance of activities that constitute an organization’s principal operations.

Assets are the resources (tangible or intangible) which provide future economic benefit to their owner.

Liabilities are the obligations of an organization to transfer assets or provide services to another entity.

Owners’ equity is the owners’ claim to the net assets (assets minus liabilities) of an organization. There are two types of owners’ equity accounts – paid-in capital and retained earnings.

Other accounts that might appear on an organization’s accounting records are losses, gains and contra accounts. Gains and losses refer to the increase or decrease in an organization’s assets and are the result of incidental transactions, not from events related to its principal operations. Contra accounts are sometimes referred to as evaluation accounts. They always accompany another account and are “contrary” to it. Fixed assets such as equipment or buildings will be accompanied by the contra account “accumulated depreciation.”

Another example of a contra account is “allowance for doubtful accounts,” which is contra to accounts receivable. It represents the difference between what an organization is owed and what it reasonably expects to receive.

Accrual Accounting

There is a specific point in a firm’s operating cycle which represents the critical event in the revenue earning process. Usually that point is when a sale is made or a service is rendered, not when payment is received. Therefore, revenue is recorded when the sale is made or the service rendered. If the sale is on credit, an increase in accounts receivable (short-term asset) is also recorded. If it’s a cash sale, then an increase in cash is recorded along with the sale. Note how the single transaction (a sale) had an impact on two accounts – sales and accounts receivable, or sales and cash.

Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) call for accountants to use accrual accounting for financial reporting. In accrual accounting, revenue is recorded when it’s earned, not when payment is received. If a firm makes a sale on credit in December 2009 and is paid in January 2010, it records the revenue in 2009 and consequently 2009 income is affected. Likewise, expenses are recorded when they are incurred, not when they are paid.

Here’s an example. Think of your favorite magazine. Assume that you paid $36 for a monthly, one-year subscription. When the publishing company received your check, it recorded an asset (cash) and a liability, or obligation, to provide you with a copy of the magazine each month for 12 months. The firm does not record revenue when it receives your payment because it has not yet been earned.

When the company sends your monthly copy of the magazine it reduces its liability by $3. It’s at this point the firm recognizes $3 of revenue, because it has now been earned.

Cash Accounting

The counterpart to accrual accounting is cash accounting. Under the rules of cash accounting, revenue is recognized when cash is received and expenses are recognized when cash is paid. Before the days of Visa and MasterCard, doctors and dentists widely used cash accounting because of the uncertainty of receiving payment for their services. Today, you are probably not going to get further than the receptionist’s desk without handing over your credit card. It’s not surprising to learn that most doctors and dentists use accrual accounting today.

Equations

There are two very simple equations around which the accounting framework is built: the income equation: Revenues − Expenses = Profit; and the balance sheet equation: Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ Equity.

Income Statement

Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.

(Charles Dickens, David Copperfield, ch. 12)

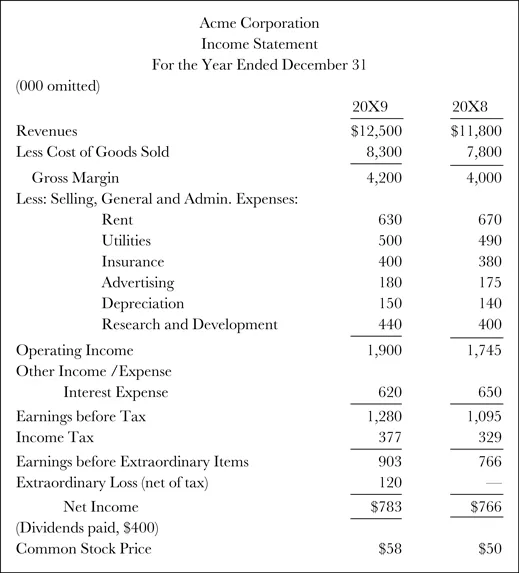

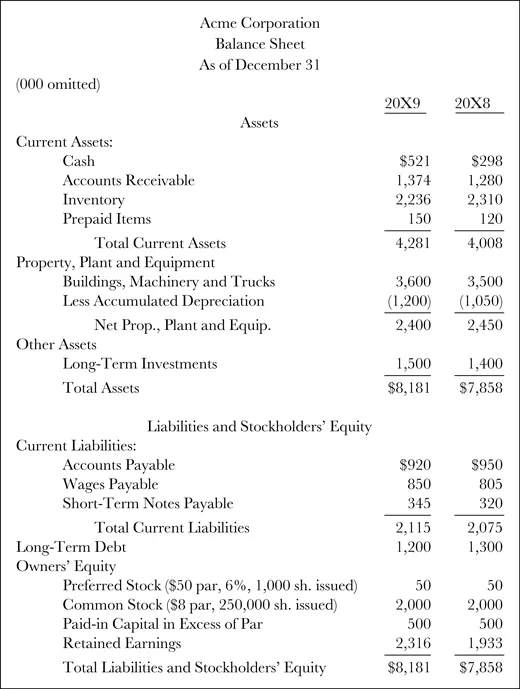

Figures 1.2, 1.3 and 1.5 illustrate a typical income statement, balance sheet and source and use of funds statement respectively. Let’s take a stroll through them.

An income statement (Figure 1.2) can be likened to a movie. It tells a story about the firm’s activities over a period of time. A firm’s income statement tells the reader what the firm earned by selling its products or services, what activities it undertook to earn that revenue and how much those activities cost. Like some movies, it can have a happy ending; like others, it can be a horror show.

The opening scene, that is, the first item on the income statement, shows what the firm’s revenues are, that is, what it earned from the sale of its principal products or services.

Cost of goods sold follows. If the company in question is a retail or wholesale firm, cost of goods sold represents the cost to the firm of the merchandise it sold plus all the related costs of transportation and taxes incurred to get the product on its shelves and out the door.

If the firm is a manufacturer, calculating cost of goods sold is considerably more complicated. It involves calculating the cost of materials and labor and estimating the overhead that went into manufacturing the firm’s products. For a service firm, cost of services provided represents the labor and overhead expended to provide the firm’s services.

Gross profit (aka gross margin) is a particularly important number on the income statement. Not only is it usually one of the larger amounts on the income statement, but it also represents the amount of money the firm has available to cover its selling and administrative expenses, interest and taxes and provide a return to the firm’s owners. If gross profit is not adequate, the firm is not going to be profitable.

Selling and administrative expenses are obvious from their titles. Of those listed in our example, depreciation deserves special mention. Like other expenses, depreciation is a cost of doing business and is deducted from revenues to determine net income. Unlike other expenses, depreciation is a non-cash expense. That is, the firm writes a check and reduces its cash balance when it pays for wages, utilities and so on. It does not do so when it records depreciation.

Jump ahead for a moment and check out the balance sheet in Figure 1.3. Notice how accumulated depreciation reduces the amount reported for buildings an...

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.1