- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Using Models to Improve the Supply Chain

About this book

Around the world, virtually every company is engaged in some form of effort intended to improve the processing that takes place across an end-to-end supply chain system as they work towards moving their organizations to the next level of performance. Supply chain, particularly when enhanced with collaboration and Internet technology, is uniquely su

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

INTRODUCTION: A SUPPLY CHAIN FRAMEWORK WILL GUIDE EXECUTION

Throughout my business experience, I have never encountered a company that did not have some form of improvement process under way. Most of these efforts were intended to cut costs as close to the bone as possible, while others had a slightly more noble intention. For a while, quality became a serious matter as we heeded the calls of Deming, Juran, Crosby, and others to pursue total quality management. Most firms set out to do things right the first time and bring processing under acceptable control limits. Some firms qualified themselves under ISO 9000, the Baldrige Criteria, or other standards, providing proof they were serious about the effort. A few even moved to six sigma standards by improving systems to generate less than 3 bad parts per million. The smart ones used quality as a rallying point to reduce costs while they made things better.

Next came a nearly universal attempt to reengineer business processing. Process maps detailing what goes on in a business became common and were useful in finding and eliminating all of the nonvalue-adding steps. As-is conditions were analyzed so teams could develop improved to-be conditions. Companies employed this technique to dramatically downsize their operations. Enormous removal of labor will be a lasting legacy for this effort as the focus was mostly on becoming a low-cost producer in an industry. What companies learned, however, was how to challenge the status quo and look for innovative ways to do the right things better.

SUPPLY CHAIN BECAME AN UMBRELLA PROCESS FOR OVERALL IMPROVEMENT

Then we discovered supply chain and realized there is an umbrella process under which the best features of the previous continuous improvement efforts could be merged with a focus on end-to-end processing that results in superior customer satisfaction. The early practitioners saw an opportunity to rethink and redesign linked process steps, all the way from initial raw materials to delivery of finished goods and services. While pursuing this opportunity, the idea of supply chain optimization developed—the chance to bring all process steps to a best-practice level and thereby optimize the total effort. Now the better right things would be at the right place at the right time.

Next came the discovery that knowledge was as crucial to success as innovative processing ideas. Those at the forefront of supply chain turned to the Internet and cyber-based technologies became feasible as a means of enhancing the improved processing. With appropriate digital-based equipment, software, middleware, and business process applications designed to enhance knowledge across extended enterprises technology blossomed as the tool for success. Those at the front of this phase also discovered that collaborative use of cyber technology could play an enormously beneficial role in bringing the linked processing to the highest level of effectiveness. Online visibility of total processing became an important feature so firms could see the right things going to the right places on time and communicate quickly if changes were necessary.

A few parameters became necessary ingredients for combining all of these emerging capabilities into a sensible strategy. The first supply chain improvement need is to establish what end-to-end means for a particular firm in order to set limits on the span of these efforts. The next step is to determine who will participate in the digital knowledge sharing and what information they should receive. Another need is to establish the scope of the ensuing advanced improvement efforts so skilled (and scarce) resources can be appropriately applied to building the new network systems while assuring returns are matched with the effort.

In this chapter, we look at the current state of the supply chain effort and use a basic framework that has proven to be very useful for understanding the dynamism of such efforts and to help calibrate a firm on its pathway to the desired level of improvement. This framework is used throughout the text to guide readers in selecting the most appropriate models and then executing properly. The author is greatly indebted to Ian Walker, senior partner for CSC Consulting, and Dr. Larry Lapide, VP of Research Operations and Business Applications at AMR Research, for their assistance in the supporting analyses presented in this chapter. The foundation for building sound and appropriate models was created with their help.

SUPPLY CHAIN DIMENSIONS SET THE STAGE FOR IMPROVEMENT

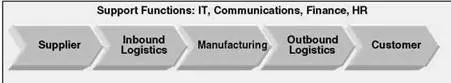

When defining the scope for a supply chain effort, it is always advisable to adopt as broad a definition as possible. That way the most process steps are included and, therefore, the greatest opportunity for improvement is considered. The only caveat is to exercise caution and not make the scope so great that insufficient resources are available to reach effective conclusions. When enthusiasm builds for such efforts, it is not unusual to see long lists of improvement initiatives generated. Too often, due to talented resource constraints, these efforts get bogged down in completing the list, rather than bringing the right initiatives toward an aligned and logical strategic intention. With that in mind, the firm gets started by deciding where its supply chain begins and ends—the dimensions for the effort. The traditional view of supply chain starts with an illustration as simple as that displayed in Figure 1.1.

The front end, or upstream dimension, begins at the point at which the firm acquires the wherewithal to start its processing. That requires a look at incoming materials and services so an immediate effort to reduce the total number of suppliers can take place. Further work in this area generally results in identifying the core group of important sources on which the firm depends. Supply chain improvement always progresses with the help of these key suppliers—never with the total array of sources. How the materials and services arrive is also documented as inbound logistics come under study. There are simply too many modes of transportation being underutilized for a serious supply chain advocate to overlook this important area. Here we consider the timing and cost of getting the materials and services to the appropriate destination.

Figure 1.1 The Traditional Supply Chain

Since some improvement effort will already be under way, the next step is to draw a process map linking these incoming supplies and services with the important internal process steps. This map need not be elaborate, but it must show the flow of products and information that results in the firm delivering products and services. The map continues through the manufacturing or production processes and on to delivery to the next link in the supply chain. Steps used for outbound logistics of what has been made must be recorded. Here we take note of the shipments leaving manufacturing or production and going to places where the goods are stored—generally called warehousing. This sector could include an intermediate distributor, but results in shipments of goods to a business customer. For some firms, the map ends at this point and the improvement process can commence. Most firms have begun their supply chain effort with a business-to-business (B2B) map.

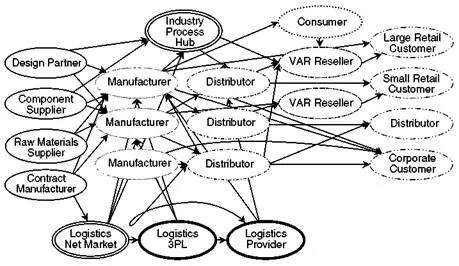

In the modern sense, the chain continues and is complete at the downstream side when the consumer is satisfied with the delivery. When that does not happen and something is returned, the chain continues in reverse. Figure 1.2 illustrates this more extended business-to-business-to-consumer (B2B2C) view. Regardless of which format is chosen to optimize any supply chain effort, a company must define the breadth of its end-to-end processing so people seeking improvement know where to begin and where to stop. That means the map must include the intermediate steps that define what happens to the products and services after the immediate business customer has been satisfied. For goods that go on to retail outlets and into consumer purchasing, the map gets extended all the way to the consumer and shows a channel for any possible returns.

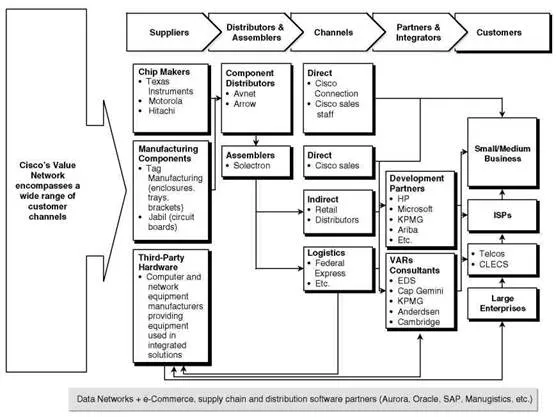

The map gets more complex as this analysis progresses and multiple supply sources and channels to market can be depicted. Figure 1.3 shows a complex supply chain system more closely depicting a modern, large-scale network. In this flow chart, the supply side is far more complex, involving multiple incoming sources of materials, as well as subassemblies, work from subcontractors and contract manufacturers. The intermediate processing could involve other network partners with better core competencies handling part of the process steps. The channels to market could include distributors and several types of business customers, including multiple retail customers. To complete the map, it should then extend to the designated consumer markets targeted for selling by the network partners.

Figure 1.2 The Extended Supply Chain

Figure 1.3 A Complex Supply Chain Network

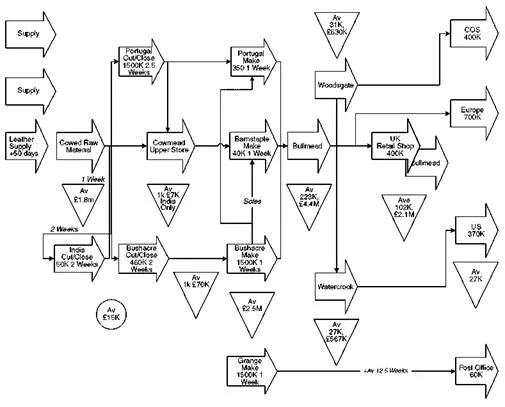

With the end-to-end dimensions determined, the Level 1 firm returns to the starting point where the attention is going to be on internal processing. Once a rough supply chain map is completed, the firm focuses on what happens within its four walls. Here the map takes on more detail as the firm decides the definition and scope of what is going to be improved. Figure 1.4 shows a detailed map of the internal processing that takes place within a particular factory making desert boots. On this map, the time frames and estimates of current costs have been included to make the map more of a depiction of what’s transpiring, so it becomes a detailed value chain.

The internal supply chain map should cover all of the physical processing—from supply through manufacture, transport, and storage to eventual sale. As each connection is made along the chain, group together the products that share mutual resources and segregate products that operate separately. The result will be a series of self-contained product flows where sharing of resources is minimal (warehousing and storage) and where competition for resources becomes a problem needing management (shipping and customer service).

Clarks Shoes made the map in Figure 1.4, one of twenty produced for each major product family. This map for desert boots immediately revealed several problem areas:

Figure 1.4 A Detailed Internal Supply Chain

- This one product flow was mapped by several functions in the organization, each having its own local performance measures.

- Production resources were often fully loaded but the result was a lot of inventory in the supply chain.

- The customer service goals were often not defined precisely, so no one knew how much it cost to provide a given level of service (Walker, 2001, p. 40).

Clarks took the segmented flows shown by the mapping exercise and created horizontal structures, what they called supply chain tubes, across the organization. Teams responsible for each tube took control over the products to be made and sold and the assets used to make the products. Each tube, or product line, is largely self-contained in this approach. As a firm pursues its mapping, groupings could be based on an identified set of assets, or a market-facing product group. When correctly depicted, there’s little trouble beginning a process improvement effort that starts with suppliers and moves through the channels to market.

With this information, teams can begin working to bring this map to a new and improved state. Such an effort always starts with a focus on internal functions and processes—to clean up existing problems, mistakes, and errors, and optimize internal efficiency. Then the focus can move outside to look at how every hand-off in the end-to-end processing can be improved and made as effective as possible for customer needs. Eventually, the effort spans a full network—an extended enterprise—and applies the appropriate cyber-based technologies to establish the most effective value chain in the eyes of the desired customers and consumers. This most advanced level will contain the greatest span of supply chain dimensions and, of course, the most work to reach completion.

Figure 1.5 illustrates a supply chain process map that spans a high-technology network. In this advanced stage, all the players are collaborating on improving the linked processing so the network gains a market advantage. Firms won’t get to this stage for a while. They need to evolve to such a stage and will have to struggle along the way with the possibilities offered by applying the new cyber technologies. These features must be built into the models used to progress across the five supply chain levels.

WITH SUPPLY CHAIN COMES AN EVOLUTIONARY PROCEDURE

Along this evolutionary pathway, firms will pass through one level at a time and must determine whether further progress is warranted. The levels in this evolution start with an introduction of the umbrella supply chain effort and move methodically to the optimal business model that makes sense for the firm and its circumstances.

Figure 1.5 A Detailed Internal Supply Chain (From Cisco Systems, San Jose, CA)

Level 1: Internal/Functional

Level 1, internal/functional, focuses on sourcing and logistics, concentrating on internal needs and business unit efficiency, while neglecting organizational synergies.

In the first level of supply chain evolution, the firm invariably works on an internal basis, seeking to expand its cost improvement effort, while focusing on total supply chain processing. The methodology is to look at functional improvement (getting better at buying, planning, warehousing, and shipping) and operational efficiency (lowest cost to manufacture), typically within a specific business unit. Departmental silos and independent operating units cover the landscape. Little cross-organizational cooperation exists in this early level and is rarely encouraged. Real savings are possible, particularly from improvements to sourcing and logistics within a business unit. The supplier base is reduced, volumes are leveraged, and costs decline. So long as quality is not impaired, savings can be significant and funding is created to continue the effort into the other levels.

In the area of logistics, transportation costs are reduced, warehouse space is...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- THE AUTHOR

- 1: INTRODUCTION: A SUPPLY CHAIN FRAMEWORK WILL GUIDE EXECUTION

- 2: A CALIBRATION MODEL ESTABLISHES POSITION AND PERFORMANCE GAP

- 3: MODELS FOR PURCHASING, PROCUREMENT, AND STRATEGIC SOURCING

- 4: LOGISTICS MODELS, FROM MANUFACTURING TO ACCEPTED DELIVERY

- 5: MODELS FOR FORECASTING, DEMAND MANAGEMENT, AND CAPACITY PLANNING

- 6: MODELS FOR ORDER MANAGEMENT AND INVENTORY MANAGEMENT

- 7: MODELS FOR SALES AND OPERATIONS PLANNING

- 8: ADVANCED PLANNING AND SCHEDULING MODELS

- 9: MODELS FOR SUPPLIER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT

- 10: MODELS FOR CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT

- 11: MODELS FOR COLLABORATIVE DESIGN AND MANUFACTURING

- 12: COLLABORATIVE PLANNING, FORECASTING, AND REPLENISHMENT MODELS

- 13: A LOOK AT FUTURE STATE SUPPLY CHAIN MODELING—THE NETWORK KEIRETSU

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Using Models to Improve the Supply Chain by Charles C. Poirier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Operations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.