- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Progression in Primary ICT

About this book

Providing an overview of the current context of ICT teaching within the primary classroom and an analysis of how to progress with it in order to enhance learning, this text:provides an analysis of what progression in ICT is and breaks this down into a series of detailed objectivesincludes 'real life' examples and case studies that highlight how pro

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralCHAPTER 1

A rationale for teaching ICT

The main purpose of this chapter is to explore beliefs about the way we think ICT can and should be taught. It is always possible to avoid giving a personal rationale for what and how we teach by referring to the National Curriculum and schemes of work. While we must be aware of the requirements outlined in national and local policy documents, a personal commitment to the content of our teaching, and the approaches that we adopt, will translate into an integrity in our classroom practice. To that end, what children learn and how they learn are examined in more detail in this chapter.

Before we start, however, it is worth pointing out two aspects of ICT that we are not aiming to cover in this book. The first is a wider justification for ICT in the curriculum. Those arguments have been very well rehearsed by others (Loveless and Dore 2002; Sharp et al. 2002; Kennewell et al. 2000; Ager 2000). The central, if not the core, position of ICT in the primary curriculum has become established, and so we focus on the values and purposes of integrating and embedding ICT in the ways we have described in the projects contained in the other titles in this series.

Nor do we dwell in this series on those aspects of ICT that concern its use solely as a professional tool, if it does not make a positive contribution to the development of ICT capability in children. That is not to belittle its usefulness as a tool for the teaching, learning and wider professional duties of a teacher; it is because we wish to scrutinise, in particular, those aspects of ICT use which help children to develop their knowledge and understanding of ICT.

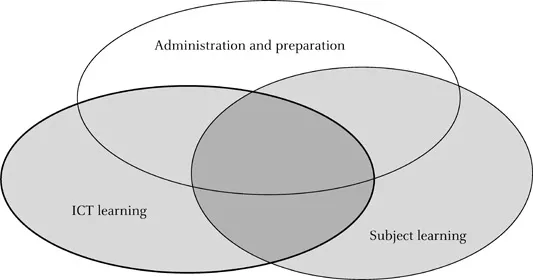

If we were to represent the totality of a teacher's professional use of ICT diagrammatically it might look like Figure 1.1.

Some ICT use by teachers is to help children achieve subject learning through activities that use existing ICT knowledge and skills to discover information or

Figure 1.1 Teachers' professional use of ICT

communicate findings. Similarly, some is for administration and preparation, to present teaching and to record children's learning. Finally, some is specifically aimed at developing children's ICT capability, and at helping them to become more knowledgeable about the subject and more proficient users. It is this last use of ICT that concerns us, in particular the intersection between ICT and subject learning. Selinger (2001) makes a distinction between teaching about ICT and teaching through ICT. This series focuses on reaching ICT capability through other subjects.

In each of the projects in the series we put forward pragmatic and instrumental justifications for teaching ICT in the ‘Why teach this?’ sections. There we discuss some of the reasoning behind the projects and why we advocate teaching ICT through the primary subjects.

In particular we discuss:

Learning and how children learn

Much of our understanding of how children learn has been influenced by theorists and researchers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; in particular the constructivist theories of Piaget and Vygotsky, interpreted by Bruner and Donaldson. Those working in early years settings continue to be inspired by the principles of Montessori, Froebel and others. None of these key theorists, however, experienced for themselves what happens when young learners are given access to the technologies which surround us in education today. The reason why their names are familiar is for the enduring resonance that their ideas have with our observations of children learning in our classrooms and the ease with which we can interpret their principles and apply them to new ideas.

Montessori, for example, believed in educating the senses through the manipulation of materials. She developed activities specifically to engage and develop children's senses. She also sought to devise materials that would ensure that children were in control of their learning, encouraging them to investigate and explore. It is not hard to imagine that Montessori would have been keen to exploit the potential of ICT to allow children to explore and investigate making their own decisions. Active learning and real decision-making has long been recognised as a powerful factor in effective learning. Through controlling events in a computer model (see Learning ICT with Maths project 8) or creating art work (see Arts projects 2 and 5) or exploring the living world (see Science projects 2 and 8 and Humanities project 7), children are able to develop their skills and understanding as they make real decisions.

Papert, inspired by Piaget, was the first of a new wave of pioneers who sought to develop ICT tools that would harness the emergent understanding of how children learn by building constructive feedback into software that responds to young learners' choices. From the initial versions of turtle LOGO (see Maths project 7) to the construction of Microworlds (see Arts project 8), the LOGO environment has been developed to mirror the building of understanding through assimilation of ideas which fit within current understanding, and accommodation of ideas that require a restructuring of our knowledge, as described by Piaget. Children developing a LOGO project are cast in the role of teacher; their errors are not their own, but misunderstanding on the part of the computer. When the software indicates that it does not know how to carry out a command, the child is faced with analysing the problem. When a turtle moves in an unexpected way the child has to think again and try to understand the way that the computer has acted on the commands given. Although the total immersion in LOGO projects has only really been achieved in some experimental settings, the provisional nature of ICT tools has enabled child centred exploration of ideas in the LOGO spirit to be realised using a range of software only dreamed of when LOGO was first conceived. When using vector drawing software (see Arts project 3), presentation software (Science project 7) or digital video (Arts project 10; Humanities project 9; English project 8), children are able to develop their own ideas, imagine possibilities and learn from the effects of their decisions.

Child-centred education has received some bad press over the years but has recently undergone a revival with the publication of Every Child Matters (DfES 2004) and the focus on individualised learning. The principle is alive in personalised learning, made possible by ICT which enables learning to be tailored to the needs of individual learners and provides instant feedback based on the choices they have made. Because of the way that ICT can put powerful tools within the reach of young children and make them more independent learners at an early age, it is possible that there are lessons for primary ICT learning that can be learned from andragogy, the study of how adults learn. Indeed, it has been argued that without a shift to more learner-centred education we will be unable to keep up with the pace of technological change, as today's children will ultimately need to be able to teach themselves. If they wait for a teacher to interpret each new development in technology during their lives they will be unable to participate effectively in society.

Lessons from andragogy and ICT, and learner-centred education

The term ‘andragogy’ was originally used to describe the study of how adults learn. It has developed into a term that emphasises learner-centred education (Knowles 1990) for learners of all ages and is particularly pertinent to views of the development of ICT capability and current calls towards more personalised learning (e.g. DfES 2004).

In this section we will consider how principles outlined in an andragogic model are particularly suited to ICT learning.

An andragogic model of learning, as we discussed at the outset, suggests that five key strategies are important for effective learning to occur:

- Let the learners know why the activity is important for them to learn.

- Show the learners how to access information to help them.

- Relate the activity to the learners' experience.

- Make sure the learners are ready and motivated to learn.

- Help them overcome inhibitions or attitudes to learning.

Although it is argued that the relating of activities to young learners' experience may be more difficult, as they have fewer of these on which they can draw, the type of autonomy that we are trying to encourage — to make independent choices in their uses of ICT — will be promoted through these more learner-centred strategies. Also the type of learning that ICT makes possible, by providing access to a vast range of information, individual support through on-line help and individual feedback on the effects of choices, as children explore simulations and develop their own ideas, makes the andragogic model particularly applicable to ICT learning.

Why the activity is important

By designing activities in each of the projects that make use of ICT for a purpose, in a context that makes sense to children, the ICT learning necessary to undertake the tasks is justified. Many of the projects (e.g. Learning ICT in the Arts projects 5, 8 and 9) also engage the children in creative activities that will lead to them not only solving problems but also finding and creating problems of their own as they strive to make things happen according to their plans and designs. These types of ‘child-created’ problems can be the most engaging, because it is important for the children to make their picture or design look the way they imagined it.

How to access information

While ‘information’ is the ‘I’ of ICT, and vast amounts of it are accessible to us, it has become ever more important for us to show learners how to access and use it. Internet searching is less like using a library an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 — A rationale for teaching ICT

- 2 — Progression in ICT

- 3 — Planning ICT

- 4 — Assessment

- 5 — Organising and managing ICT

- 6 — The future

- Appendix: Learning objectives for each project covered by the subject books

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Progression in Primary ICT by Richard Bennett,Andrew Hamill,Tony Pickford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.