- 193 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Strategic Planning for Water

About this book

Strategic Planning for Water examines the neglected relationship between planning for water and spatial planning. It provides the background to sustainable water management and assistance to spatial planners in understanding the complex water environment. This extremely topical book examines the challenges of:how to ensure that water supplies are a

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Strategic Planning for Water by Hugh Howes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

A favourable climate for integrating water management and planning

Sustainable development is not a new concept any more but only recently has it risen up the political agenda and become an issue of which the general public is aware. It has also been a challenge for the planning profession to take on board. When the Environment Agency was set up in 1996 it acquired a duty to promote sustainable development. During its 11-year life the Agency has been exploring a whole series of avenues to achieve this. Changes to the law on town and country planning have helped this process.

This chapter will look first at how the planning system is evolving, how this evolution is helpful to the promotion of sustainable water management and the potential dangers which these changes may present. Second it sets out the various plans and strategies that deal with water management and how they relate to town and country planning. It provides a guide for those planners who are anxious to know more about the water environment and how it should be built into Regional Spatial Strategies and Local Development Frameworks.

Ten years ago sustainable development was considered to be a somewhat marginal concept pursued only by extreme environmentalists. Now political parties seek to outdo each other in terms of the sustainability of their policies. Sustainable development involves reconciling the need for economic development and social advancement with protecting and enhancing the environment without compromising the quality of life of future generations or their ability to improve it further. A good start has been made in that environmental considerations are no longer being treated under the planning system simply as a ‘follow-on’. They are now being given the more central role in the planning system that is implicit in the holistic concept of sustainable development.

Sustainability is sometimes seen as being opposed to development. However, if planners are resourceful and imaginative development can generally be achieved in ways that are compatible with protecting and enhancing the environment. The root of the issue as far as water management is concerned is the impact of development on the hydrological cycle. The hydrological cycle is essentially the natural seasonal cycle from the point where rain falls to where water flows out of an estuary into the sea. It also includes the human-centred interventions where water is abstracted from the natural environment for consumption and returned to that environment via the discharge of treated waste water. Virtually any change of land use makes demands for supplying water and for treating waste water and thereby increasing the scale of such interventions. It is also likely to increase the amount of surface water running off from the site, thereby affecting the quality of water in nearby watercourses and increasing the risk of flooding downstream. In summary, what is important is the quality and quantity of development, its impact on a particular location and what measures can be taken to mitigate such impacts.

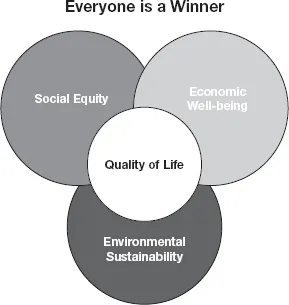

Figure 1.1 Sustainable development

Figure 1.2 The Environment Agency puts sustainable development into practice. Red Kite House, the Agency’s office for the West Area of its Thames Region in Wallingford, is one of the most environmentally friendly buildings in the country. It is naturally ventilated, well insulated and the glazing reflects the heat of the sun. Little energy is used for heating or cooling. Solar panels generate 25 per cent of the energy used to heat water and photovoltaic panels provide 20 per cent of the electricity required. Rainwater is harvested from the roof and reused in the building. (Photo: Environment Agency)

The powers and duties of the Environment Agency

The setting up of the Environment Agency in April 1996 was seen as an important step in taking forward the Government’s policies on sustainable development. In 1982 the House of Lords Select Committee had charged the water authorities to have regard to the environment when carrying out their land drainage functions. In 1989, the National Rivers Authority (NRA) was formed when the water authorities were privatised. It was charged with protecting and enhancing the environment.

The Government went a stage further and required the Agency, in discharging its functions, to make ‘a positive contribution towards achieving sustainable development’. There was no indication as to how these requirements were to be carried out. However, Brundtland’s words, ‘without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (widely known as the intergenerational equity principle) have influenced the Agency’s work ever since. From its inception the Agency has developed techniques for delivering sustainable development on the ground. It means balancing the prospects of economic growth and the alleviation of poverty and social exclusion with the protection and enhancement of the environment. This involves taking into account scientific uncertainty and the precautionary principle, as agreed at the Treaty of Maastricht by the member countries of the European Union. If an optimum balance between these three elements can be achieved then the quality of life can be enhanced. This will be a major theme in future Regional Spatial Strategies and Local Development Documents and one to which the environment can make a major contribution. Techniques for taking forward this agenda are examined in Chapters 7 and 8.

The Environment Agency remains a statutory consultee under planning legislation. It is entitled to be consulted by Local Planning Authorities on a range of planning applications and on all development plans. It is also entitled to give advice on these matters but the ultimate decision remains with the Local Planning Authorities, which may or may not take such advice. A vital role is to advise Local Planning Authorities on how the impacts of development can be both minimised and mitigated. It is then up to Local Planning Authorities to ensure that the technical measures to achieve this are included in the granting of any planning permissions. The Agency might also provide advice on the full range of environmental matters which may, for example, include the interface with economic growth and alleviating social deprivation. In addition the Agency is anxious to advise Local Authorities on the environmental content of the full range of additional tasks that they are now facing. It is particularly keen to contribute to the sustainable communities and regeneration agendas and to work with Local Authorities to integrate better with these planning processes and to achieve a better joint understanding of local environmental issues. But its role, as far as the planning system is concerned, remains essentially persuasive and success depends on the Agency’s assuming a strong advocacy role.

In dealing with development the Environment Agency will have to have regard to its twin duties under the Environment Act 1995:

• A principal aim of the Agency is discharging its functions to make a positive contribution towards attaining the objective of achieving sustainable development (Section 4).

• General duty to have regard to cost and benefits in exercising its powers (Section 39).

In giving its advice referred to above, the Agency must take account of costs and benefits of potential environmental enhancements to the development industry. Such costs must be ‘reasonable’. Chapter 7 provides an indication of what ‘reasonable’ should mean in this context.

The implications of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004

The Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act (2004) and contingent Planning Policy Statements have made significant changes to the planning system. In brief, there will be a simpler and more flexible plan-making system. There will be procedures for speeding up major infrastructure projects and a simpler and fairer compulsory purchase regime. The new system provides additional opportunities to promote sustainable water management with significant implications for the Environment Agency’s involvement in the planning process. In particular:

• Local Development Frameworks are seen as a delivery mechanism for community strategies which will cover health, economy, safety, skills and the protection of the environment.

• Local and strategic partnerships have a key role in bringing a range of key stakeholders together to achieve things that would not otherwise happen.

Other important changes to the planning system which will have a bearing on environmental issues include:

• Establishing ‘contributing to the achievement of sustainable development’ as a statutory purpose for planning.

• The replacement of regional planning guidance by ‘Regional Spatial Strategies’ which will be statutory and part of the development plan. They may include ‘sub-regional spatial strategies’, intended for areas where there is a ‘strategic planning deficit’.

• The replacement of local plans and unitary development plans by Local Development Frameworks made up of a number of ‘Local Development Documents’ which have to be completed by the autumn of 2007.

• Making it a statutory requirement that development plans are subject to a sustainability appraisal. They will also be subject to the Strategic Environmental Assessment Directive.

Regional Spatial Strategies and Local Development Documents will contain fewer policies than their predecessors but they will be supported by an indication of how they are to be implemented. Indeed, means of implementation, and particularly financial mechanisms, are likely to assume an increasingly high profile in the planning process. The economics of development are, therefore, likely to impinge on the work of planning officers to a greater extent than in the past. These implications are considered in Chapter 7.

The implications of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act are still being evaluated. The overriding message is that there will be less emphasis on formulating policies and more on implementing them. Already the Government is looking to further changes to the planning system. Reference to a new Planning Bill was included in the Queen’s Speech in the autumn of 2006. Its content will presumably be based on the second Review by Barker (see below) which was published in December 2006 and is mainly concerned with the efficiency of the planning system. A White Paper was published in the spring of 2007.

The new planning system, brought in under the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004, placed more emphasis on enabling development to take place. On the face of it this might mean that development would only take place at the expense of greater damage to the environment. This was acknowledged by Barker herself. In July 2004 she appeared before the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee, where she acknowledged that any increase in house building could result in an impact on energy and water but that the implications would not be ‘very extreme’. She indicated that the government had to weigh up environmental damage against the need for a ‘more ambitious’ house building programme that would make it easier for first time buyers to be able to afford homes. This implies that the planning system is seen as primarily a mechanism for delivering more housing and could mean that such housing might not necessarily be provided in the most sustainable manner.

The two Barker Reviews (HM Treasury 2004 and 2006a) were commissioned by HM Treasury to consider the issues underlying the lack of supply of housing and responsiveness of the housing market in the UK compared to other European states. The first was concerned primarily with the supply of housing and how far the lack of affordable housing was an obstacle to industrial productivity which, as will be seen in Chapter 7, does not compare well with either other European countries or the US. The approach adopted by Barker was essentially to examine what ‘obstructions’ there were, particularly in the planning system, which prevented the completion of a greater number of homes. This leaves open the question of whether environmental considerations were construed as such an ‘obstruction’. It recommended the setting up of a ‘community infrastructure fund to unlock some of the barriers to development’.

The second Barker Review examines how planning policy ‘can better deliver economic growth and prosperity alongside other sustainable development goals’. This review of the planning system scrutinises the way that planning impacts on economic growth and employment. It analyses the effects of planning on enterprise, competition, innovation, investment and skills. Economic growth, and increased efficiency of the planning system to help deliver it, are clearly high on the government’s agenda but the apparent lesser concern for the environment seems not to support the concept of sustainable development. Is there a danger that environmental consideration will once again be relegated to a secondary consideration? There seems to be little recognition in these reviews that environmental planning can play a catalytic role in contributing towards social and economic ends. It is clearly in the interests of planning authorities and their various partners to emphasise the potential benefits to be derived from the environment in general, and the water environment in particular, at an early stage in the planning process to ensure that the house building programme is carried out as sustainably as possible.

The Department of Communities and Local Government (DCLG) published three significant consultation papers at the end of 2006, all of which were aimed at reducing the environmental impact of new development. The first, Building a Greener Future – Towards Zero Carbon in New Housing (DCLG 2006a), aims to reduce the carbon footprint of new housing development. The second is a draft Planning Policy Statement, Planning and Climate Change (DCLG 2006b), which sets out how planning, in providing for the new homes, jobs and infrastructure which are needed by communities, could help to shape developments with lower carbon emissions and which are resilient to climate change ‘now regarded as inevitable’.

The third, and most significant for the management of water, is Mandating Water Efficiency in New Buildings (DCLG 2006c). This sets out the government’s proposals to make minimum standards for the efficient use of water mandatory in all new homes and commercial developments in the face of rising demand for water, growth in housing and the changing climate. The consultation paper is concerned with the aspect of the ‘twin track approach’ that is concerned with the better management of existing resources and not with the second track which is concerned with providing new resources. It acknowledges that resources are under pressure, particularly in the South East. It seeks to reduce water consumption from 150 litres per person per day to something in the range of 120–135 by setting minimum standards for water use in new buildings. Building regulations and water fittings regulations are seen as the main formal mechanisms for achieving this. But behavioural change is also seen as having a role to play.

These recent and prospective changes in the land use planning system in England and Wales, with the increased emphasis on implementation, have provided an opportunity for the Environment Agency, water companies, government departments, the Local Government Association and professional bodies to work together more closely than in the past. The changes will help to ensure that development proposals can be implemented in such a way that their impacts are first minimised and then mitigated. A particular priority is to ensure that appropriate references to the Water Framework Directive are made in planning documents. River Basin Management Plans, to be prepared under the Directive, will provide a powerful new vehicle for articulating environmental issues. Obtaining the greatest benefit from these plans will require much cooperation between all parties involved. Chapter 5 sets out the potential opportunities of the Directive and provides guidance to Local Authorities on the part ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword by Professor John Gardiner

- Preface

- Introduction: a changing culture for managing water

- 1 A favourable climate for integrating water management and planning

- 2 The path to sustainable water management

- 3 Regional planning: a better water environment in London and the South East

- 4 Promoting the effective use of water

- 5 River Basin Management Plans

- 6 Managing river basins: two case studies

- 7 Promoting prosperity through a better water environment

- 8 Alleviating poverty and social exclusion through a better water environment

- 9 An environment for prosperity and quality living

- Appendix: process table for identification of implementation mechanisms

- References

- Index