The earliest descriptions of the syndrome, dating back to 1954, were given by Andreas Rett, an Austrian pediatrician, the syndrome later being named after him. It is a rare pathologic condition, almost exclusively typical to the female gender, normally characterized by altered mental and psycho-behavioral development, with symptoms showing a few months after birth in apparently normal conditions. The first part of the chapter deals with the evolvement of the syndrome, which is quite rapid, reaching maximum severity in most cases. We will also argue the clinical features of the full-blown condition. These features can be promptly identified with specific, stereotyped behaviors, such as waving and rubbing of hands, beating of the chest, biting fingers, sudden shouting, a lack of interest in the immediate surroundings, microcephalism, severe intellectual disability, and hypotonia. In the second part of the chapter, comorbidities will be dealt with: epilepsy, delayed growth, dysautonomia, adverse bone health and scoliosis, and sleep disturbances.

1.1 Features of Rett Syndrome

In 1966, Andreas Rett reported for the first time the clinical features of the syndrome that would later bear his name. His work consisted of a description of young females with similar characteristics and represented a milestone of this field (Rett, 1966). Rett was initially impressed by almost identical stereotypic hand movements, which represented the first description of the gestalt of Rett Syndrome (RTT) whose clinical diagnosis has been progressively refined to the last publication of revised diagnostic criteria in 2010 (Neul, 2010).

RTT as a new nosographic entity was introduced by Bengt Hagberg and colleagues who identified clinical signs in their own patients, and their publication represented the initial clinical description of 35 cases of RTT in the literature in the English language (Hagberg et al., 1983).

Since Rett’s first recognition of it in 1966, several papers on RTT have been published, and the identification of genetic causes of this syndrome represented a boost to the research on this topic.

The classic signs and symptoms of RTT include many functional impairments, leading to the substantial necessity for support in daily life, rendering the patients a social and economic burden, and requiring parents and caregivers to also be deeply emotionally involved. The classic clinical features of RTT consist of severe functional impairments, which are characterized by either gradual or sudden loss of hand and communication skills, loss of balance, and development of hand stereotypies (Lee et al., 2013; Leonard & Bower, 1998; Neul, 2010). Significant associations between pattern genotype and the clinical hand and gross motor skills exist (Bebbington et al., 2008; Downs et al., 2010, 2016a; Fehr et al., 2013).

At the onset of the clinical manifestations, subtle changes in development often precede the regression, which is characterized by either gradual or sudden loss of hand and communication skills, balance and presence of stereotypies (Fabio et al., 2009). The first signs often include reduced hand control and a decreasing ability to crawl or walk normally. Eventually, muscles become weak or may become rigid or spastic with abnormal movement and positioning (Lee et al., 2013; Leonard & Bower, 1998; Neul, 2010).

Parents often say that the symptoms usually noticed first are floppy hands and legs, incessant crying, and the obvious disappearance of previously acquired skills. They also observed that if their child had been able to speak a few words or walk several steps before the onset of the symptoms, she would gradually lose the skills she had gained and in time, she may lose the ability to speak and walk completely. She will develop stereotypical behavior such as wringing, clapping, or patting of hands. However, the progression of RTT varies from one child to another. For example, some parents note that their daughter has lost her ability to walk, others that she is still able to, but will display a stiff-legged walk. Lucia, the mother of Teresa says:

“Our daughter Teresa was almost two years old when she began struggling to walk, to crawl and to talk … she repeatedly clapped her hands”.

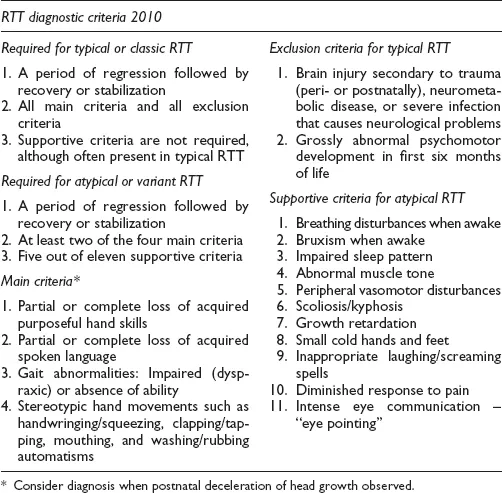

Originally, RTT was recognized solely on the basis of a clinical diagnosis, considering the Vienna diagnostic criteria and later, recommendations by American researchers. For epidemiological research, it was recommended to include only patients diagnosed as classic cases of RTT. Later in time, subjects not fulfilling all the necessary criteria were also considered as atypical RTT, such as congenital, childhood seizure onset, male, late childhood regression, and preserved speech variants (Goutières & Aicardi, 1986; Trevathan, 1989; Zappella, 1992). For example, Hagberg and Skjeldal (1994) suspected atypical RTT development in a ten-year-old girl with intellectual disabilities and he thought that the diagnosis required the presence of three or more primary criteria and five or more supportive criteria.

Today, clinical diagnosis involves a slight expansion of the exclusion criteria, and the evaluation of new criteria relating to breathing dysfunction, peripheral vasomotor disturbances, seizures, scoliosis, growth retardation, and small feet (Hagberg et al., 1985; Neul, 2010).

In accordance with the revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature by Neul (2010), the clinical picture associated with typical RTT is defined by a regression of purposeful hand use and spoken language, with the development of gait abnormalities and hand stereotypies. After the regression phase, a period of stabilization and potentially even improvement follows, with some patients partially regaining skills. This potential for some skill recovery emphasizes the importance of the acquisition of a careful anamnesis to determine the presence of regression (Neul, 2010).

As there are no clear signs of impairment until the age of six months, parents and primary clinicians are usually not concerned about development which seems to be in line with a physiological one.

In the atypical RTT, known as the congenital variant, there is early abnormal development from birth; that is the reason these forms should be evaluated using the atypical RTT criteria.

In recognizing RTT, clinicians and teachers sometimes detect some suggestive clinical features and refer children for comprehensive evaluation due to the presence of signs or symptoms such as slowing in the rate of head growth, breathing abnormalities, and the intensive “Rett gaze” used for communication. These clinical manifestations are reported in the criteria for atypical RTT too (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 RTT diagnostic criteria

It is known that RTT may also be observed in males, although initially it was recognized only in females, and that specific genotypes may be associated with different signs and symptoms, and may also be associated with severe cases of the syndrome (Bebbington et al., 2008; Downs et al., 2010, 2016b).

Adults with RTT but who have preserved the capacity to walk have a mutation associated with a milder phenotype (Anderson et al., 2014; Foley et al., 2011). In the same way, for communication skills, those with milder mutations such as Arg133Cys or Arg306Cys are more likely to learn to babble or use words before regression, to regress later, to retain some oral communication skills and the capacity to walk after the regression phase, and to be diagnosed later (Anderson et al., 2014; Fehr et al., 2011; Foley et al., 2011; Urbanowicz et al., 2015).