- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Future Healthcare Design

About this book

This book describes how architects can design better healthcare buildings for a rapidly changing context and climate. Innovation in the design of healthcare estates is essential to the sustainability of our health services. Design thinking in this field is being influenced by a range of factors, such as economic constraints, an ageing demographic, complex health conditions (co-morbidities), and climate change. There is an opportunity for architects and designers to be innovators in the future of healthcare through the design of buildings and cities that offer wellbeing and healing. It highlights the latest innovations in key areas of practice and research, with a range of case studies to provide practical lessons and inspire better design.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Future Healthcare Design by Sumita Singha in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

ORIGINS OF THE BRITISH HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

‘Bad sanitary, bad architectural, and bad administrative arrangements often make it impossible to nurse. But the art of nursing ought to include such arrangements as alone make what I understand by nursing, possible.’1

Florence Nightingale, Notes on Nursing, 1859

Figure 1.0: Europe’s fifth-tallest tower, The Shard, vies with the world’s second-tallest hospital, Guy’s, to the right, with the 19th-century Nightingale wards in the foreground, in London. As cities grow denser, we need to think about where hospitals really need to be rather than just stick to historic sites.

The formation of the NHS was (and remains) hugely admirable, given that the UK was recovering economically and psychologically from the effects of a devastating war. Although the idea was simple – to provide free healthcare at the point of delivery – it is this very simplicity that also led to problems that now threaten its existence. Providing universal healthcare for free or for very little money has always been difficult, as this chapter shows. However, inventive solutions were found during dark times, and we should remain hopeful that these lessons from the past will help us find radical new solutions for the future.

Figure 1.1: St Bartholomew’s Hospital is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 by Rahere, a favourite courtier of King Henry I. After Henry VIII rescued it from financial ruin in the 16th century, it became known as the ‘House of the Poore in Farringdon in the suburbs of the City of London of Henry VIII’s Foundation’, though now it is known simply as Barts.

The seeds of the NHS were sown in reform of healthcare for the poor during the Victorian era, and from ‘the anxiety of medical men to come to grips with the most glaring problems of diseases’.2 Mechanical and technological progress during the Industrial Revolution brought with it pollution, whose effects were unknown at the time. The terrible environments created new occupational hazards, such as injuries, lung diseases and bone deformities. Combined with the outbreaks of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, typhus and cholera in the general populace, cities appeared to be teeming with injuries, sickness and death. It was said that only 10 per cent of the population of Leeds was healthy. The 1842 report by the British social reformer Edwin Chadwick, ‘Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain’ (1842), showed that the life expectancy of an urban dweller was less than that of a person living in rural surroundings, and this figure was also affected by social status and wealth.

An inventory of English healthcare buildings from 1660 onwards contains several types of buildings – general hospitals, cottage hospitals, workhouse infirmaries, hospitals for armed services, specialist hospitals, hospitals for infectious diseases, mental hospitals, and convalescent homes and hospitals. Wealthy people were largely cared for at home. Most had at least one servant and could afford private doctors to visit and nurses for aftercare. The Poor Laws had a direct effect on the provision of healthcare for the poor, particularly in London. King Henry VIII consented to re-endow St Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1544 and St Thomas’ Hospital in 1552 on the condition that the wealthier residents of London pay for their maintenance. But the voluntary contributions and Sunday collections in churches were not enough, so London instituted a mandatory Poor Rate in 1547.

Ironically, charitable hospitals generally refused access to those suffering from chronic illnesses, dying patients and the destitute – perhaps due to the lack of staff needed to care for them. So the concept of workhouses and their associated infirmaries started from the 17th century onwards, providing much work for architects and builders over the next 200 years. People found begging were punished severely, sometimes by death, so the new workhouses enabled them to ‘to live a life of honest independence’ as well as giving them shelter, clothing and food. The various pre-Victorian laws were formalised in the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 (the same year as the RIBA was given its Royal Charter). Wealthy people paid a ‘poor rate’ to fund the workhouses. But help was given out reluctantly, sometimes too late, and under heavy scrutiny.3 Workhouse infirmaries were also crowded and dirty, and lacking in trained staff.4

For injured or ill military personnel, healthcare was dispensed from some very strange places – from underground tunnels, to railway carriages, to decommissioned warships. Sometimes, the hospital moved through various homes – the Dreadnought Seaman’s Hospital for retired or injured seamen moved through three different decommissioned ships during the 19th Century. In 1692, the reigning monarchs, William and Mary, commissioned a retirement home for seamen. It was designed by architects Christopher Wren and Nicholas Hawksmoor in 1696. The infirmary nearby was designed by architect James ‘Athenian’ Stewart in 1763. After the inpatients of the quarantine ship HMS Dreadnought moved in there in 1870, it became known as the Dreadnought Seaman’s Hospital. It is a testimony to the power of good design, adaptability and construction as well as the resilience and patience of hospital staff that it only closed in 1986.

There were also voices of reformers, such as Richard Oastler, the 18th-century politician, who called the workhouses the ‘prisons of the poor’, and Charles Dickens, who considered the Poor Law utterly un-Christian. As a journalist, Dickens investigated healthcare issues of his day (he also visited HMS Dreadnought), and many of his novels highlight the inhumane conditions of the workhouses and infirmaries. The emotional power of the writings by Dickens and others brought moral pressure on those wealthier in society able to help in building or adding to existing hospitals. And these actions came to form parts of the present NHS estates. For instance, Guy’s hospital had been the result of Thomas Guy’s fortuitous success in the South Sea bubble. In 1721, he built a new hospital for the ‘incurably ill and hopelessly insane’. By the early 19th century, this building was bursting at the seams. A bequest of £180,000 by William Hunt in 1829, one of the largest charitable bequests ever made in England, enabled the hospital to have 100 more beds and expand further in 1850.

Figure 1.2: One of the two inner quadrangles of the Victorian parts of Guy’s Hospital, one of which contains the statue of Lord Nuffield, who was the chairman of governors and a major benefactor. The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein worked incognito here between 1941 and 1942 as a porter and ointment maker.

Lunatic asylums or ‘madhouses’ were the other remnants of the Victorian era that remained in use well into the 21st century. The Victorian asylums were often cruel and chaotic places (the word ‘bedlam’ comes from a lunatic asylum – the Bethlem Royal Hospital). Until the 1980s, mental health was treated much like physical health. Inpatients were treated inhumanely and experiments with new drugs or brain surgeries carried out without proper consent. Despite the commitment of the then health minister, Enoch Powell, to shut down asylums in the 1970s, most of them were still in use throughout the 1980s. The final lunatic asylum only closed in 2003. Care homes for teenagers with severe mental health difficulties are still needed. Better diagnosis and new treatments for mental health disorders may find their expression in new types of facilities to deal with them (see Chapter Six).

Ward designs

The ideas of supervision and efficiency have influenced the design of modern healthcare buildings and patient areas. Single-room units or cells are physical ways of isolating infectious or disturbed patients. This layout is based on monasteries or prison cell layouts with single rooms serviced by corridors; also a typical almshouse layout. This type of design remained popular because it also conveyed the impression of austerity, efficiency and discipline, especially during the workhouse era. For example, the Woolwich Road Workhouse and Vanburgh Hill Infirmary erected in 1839–1840 was described by its architect, R.P. Browne, as ‘plain but cheerful and almslike’.5

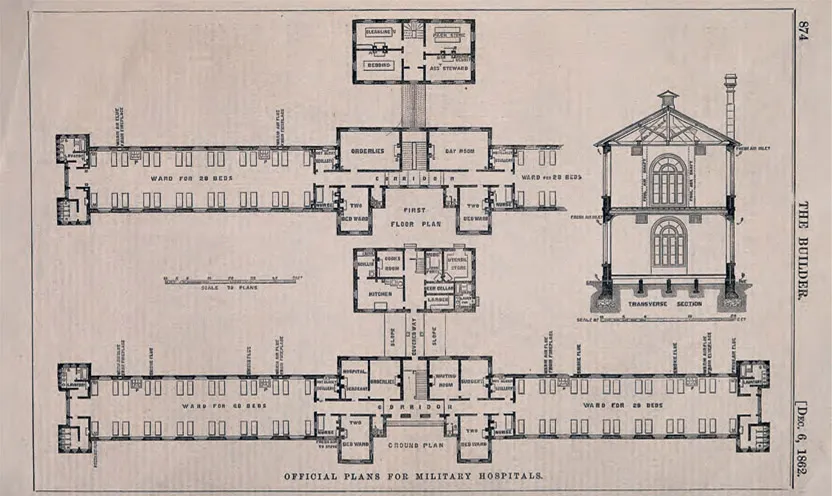

Figure 1.3: An official floor plan and transverse section with scale for new military hospitals, c. 1862. The design principles were based on direction from Florence Nightingale. Wood engraving after D. Galton.

The other influential ward design came from the Royal Frederiks Hospital, Denmark’s first public hospital, which offered free healthcare for the poor. The hospital was designed by two architects, Nicolai Eigtved and Laurids de Thurah, and built during 1752–1757. The wards were long galleries, their sizes determined by the dimensions of a bed and circulation spaces. There was unobstructed access to each bed, windows to provide natural light, and good care. The garden in the middle of the hospital provided more areas for sunshine and fresh air. By the time this hospital closed, the Rigshospitalet (hospital of the people) had opened in 1910. It also featured wards with 20 beds punctuated by private bathroom and storage areas. With its wide picture windows and only 34 per cent solid wall, it increased both the quantity and the quality of patient insolation and ventilation.

A quirky circular ward design came from the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) and his architect, Willey Reveley. Bentham, who took a great interest in medical matters, had bought shares in University College Hospital. He coined the word ‘panopticon’ in 1796 to describe a radial design for prisons. The biggest advantage of the panopticon was the ease of supervision, so it was recommended for prisons, hospitals and asylums.

Figure 1.4: Plans of East Sussex, Hastings and St Leonard’s hospitals, 1885 (architects: Keith D. Young and Henry Hall). Note the panopticon-type layout of the male and female wards. Despite criticism by health reformers such as Henry Saxon-Snell, such ward forms continued to be presented by Victorian and modern architects.

Figure 1.5: Left: Block hospital centred around a courtyard: plan of Barts, London, 1893. Centre: Pavilion hospital: plan of Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge, 1893. Right: Corridor hospital: plan of Royal Infirmary, Dundee, 1893. Modern hospitals feature variations of these types.

Florence Nightingale’s evidence-based analysis and her experiences of nursing in the Crimean War enabled her to propose what are now called ‘Nightingale wards’ or pavilion designs. Her observations were based on studies from the work of earlier doctors and engineers who had been working on the ventilation of ships, schools, sewers and railway carriages, and George Godwin, an architect with a strong interest in healthcare architecture (and the editor of Builder magazine). She also was influenced by the planning of several older hospitals in Europe (such as the Royal Frederiks Hospital), and David Boswell Reid, who devised comprehensive ventilation systems for hospitals in London, Copenhagen, Chicago and New Yo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- Acknowledgements and Dedication

- Preface

- About the author

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1 Origins of the British Healthcare System

- CHAPTER 2 Financing Healthcare Estates

- CHAPTER 3 Getting into Healthcare Design

- CHAPTER 4 The Brief and the Process

- CHAPTER 5 The Modern Hospital

- CHAPTER 6 The Future of Healthcare

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Image credits